The Internet exists because, in the early seventies, the US military realised that an enemy attack could make communications impossible - they needed a system that would work without vulnerable control centres. At first it linked just seven computers in the UK, US and Norway. Now it links 2.2 million over both public telephone networks and dedicated lines.

If the Internet’s present rate of growth continues, it will have 200 million users by 1995. If it were a country, it would be applying for a seat on the UN Security Council.

The original intention was that vast chunks of data would be pumped between the computers but to the surprise of the military planners, the academics who actually operated and controlled the Arpanet very quickly started using it like a telex line - to send private messages called e-mail about whatever interested them.

Until recently, however, the Internet was a minor backwater in the computing world. Today, as the planet’s biggest computer network, it links many other networks and is the most concrete, if least tangible, manifestation of the information age. Most of us still see those with the skills to use the screens, terminals and modems that access to the Internet requires as ‘geeks’ in anoraks. But to call someone a geek may yet become a compliment.

The Internet already has more than 35 million users, and that number is growing at 20 percent a month. You need a personal computer, a phone line and a modem to translate information from the computer into sounds transported along the telephone wire. It then becomes possible to look up CIA archives in Washington DC or send a book to Moscow in minutes, or to conduct a conference in an obscure part of South America, almost as easily as you can dial the local library - and for the same price, the cost of a local phone call.

On a typical day last month, one part of the Internet called the World Wide Web added the following services: two new electronic (on-line) magazines, brochures for Bridgewater College and the University of Singapore, a Cordon Bleu cookery corner, a history of Palo Alto, California, a new guide to the Internet, an Internet Chess Server, an electronic clearing house for health science information, some new technical services and the TV series Blake’s 7 (scripts and video excerpts).

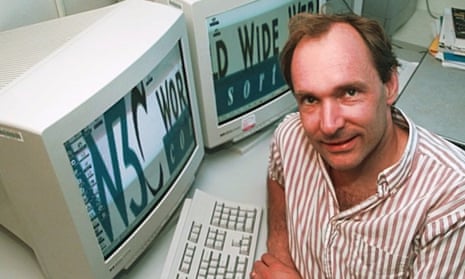

The biggest problem is how to find your way in this sea of information. The World Wide Web is a way of organising information, to make it navigable. Web pages are a growing proportion of total Internet traffic. Anyone can post Web pages, creating links between different pages on distant computers, which anyone else can read. Eventually every page will contain multiple links to other pages.

‘I don’t know one per cent of what’s out there,’ says Tim Berners-Lee, a British computer scientist who designed the Web. ‘It’s worse than asking the architect of a library what books are on the shelves.’

In the United States, President Clinton came to power promising to build an ‘information superhighway.’ The Americans were quicker than us to recognise the potential of the Internet as the prototype of a new world order - BT’s data services are still not connected to the Internet. ‘It’s embarrassing,’ admitted one of their most senior executives. ‘We’re working on it.’

The metaphor of the Internet as a road that carries information instead of people or goods is a useful one. It is a global motorway network and the World Wide Web links are like short-cuts between highways.

The big question is: will the superhighway become a toll road? Commercial forces are gathering, but for now access is almost free. The Internet is used to carry on affairs, run businesses, join specialist discussions and transport data on any subject imaginable. A world of information is waiting on distant computers: food and music and politics; art and weird sex and whistleblowers; philosophy and every other academic endeavour in text, in fuzzy images slowly growing sharper, and in video that is slowly approaching the quality of crisp TV.

Among the nine thousand or so special interest groups, called the Usenet groups, you certainly do meet all sorts. Though only a tiny fraction of total Internet traffic, Usenet ranges from arcane subjects like encryption through to showbiz gossip. Pornography is popular - 11 of the 25 most-used discussion groups are porn-related.

The Usenet is a phenomenon that could only have arisen out of the open architecture of the Internet. Until recent changes made the Internet accessible to the non-specialist however, it was geek heaven - the preserve of computer nerds, academics and enthusiasts who spent long nights sitting at computer terminals, tapping out electronic-mail.

E-mail is how Internet users speak to each other. They even have special sub programs called ‘bozo filters’ built into their e-mail software - so they can stop selected other users from bothering them by filtering out their messages.

The Internet emerged into mainstream society last January, when Rupert Murdoch and the heads of ABC, MTV, Walt Disney, Sega, AT&T, Apple and other computer, phone and entertainment companies met in Los Angeles to inaugurate what they called Infobankingshoppingtainment.

Their money and expertise is needed. These are early days, and accessing distant computers can be frustratingly slow. Skill is needed, and training can be expensive. There will be problems of information overload as well as system overload problems of privacy and access, copyright and control. But these are the problems of success and they will be solved. Truly, the geeks shall inherit the earth.

This is an edited extract, click to read more

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion