‘The great medical powerhouse has no doctors’: Parents of sick children denounce the health crisis in Cuba

In addition to the lack of medicine and supplies, the exodus of health personnel has increased due to the island’s economic problems

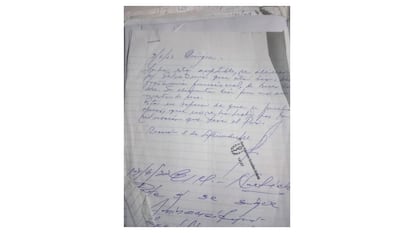

On a random piece of paper, what looks like the page of a school notebook, Dr. Goar Valeriano Gonzalez informed Maydelis Solano of the impossibility of operating on her son. The Pediatric Hospital of Holguín does not have the resources to do it, he says, and Jordan Daniel Montero Solano, 13 years old and barely 28 kilos (62 pounds), will continue not knowing what it is like to eat through his mouth. “He is waiting until he can be operated on,” the surgeon wrote in blue pen. “It has not been done because of the situation in the country,” he clarified. Then Dr. Goar stamped his signature and an official stamp of the Cuban Ministry of Public Health (MINSAP), as if to prove that the lined school notebook page really is his medical history.

Several times a day, Solano places a syringe on one end of the tube attached to Jordan’s stomach. The syringes must be reused indefinitely and washed with hot water. The tube should be changed every 21 days, but Solano extends them for up to two months, during which time she saves the 600 pesos (almost two dollars at the exchange rate) to buy another one in the informal market. The child can only eat liquid food: milk, maicena (a cornstarch-based dish), yogurt, fruit juices, compote and purees made of root vegetables or meat, whatever his mother can get. But Jordan’s food consumption is getting worse and worse. He suffers from esophageal atresia, a congenital condition in which part of the esophagus, which connects the stomach to the mouth, did not develop properly. “His bones are degenerating already, impeding his motor skills,” Solano laments. “In addition, he is chronically malnourished due to the [level of] nutrition he has had in his 13 years of life.”

His mother has sent countless letters to Cuban government offices, but she has only received a response that says that her “request has been transferred to the Ministry of Public Health.” She has received other replies like “we thank you for your communication” and “your matter has been received and can be followed up on,” correspondence that speaks less about a child’s health than of the state’s inefficiency.

When Jordan was small, the doctors could not operate on him until he gained weight. When he gained weight, they could not treat him because of the coronavirus crisis. Now, Jordan urgently needs surgery and there are no supplies. There is also no gauze, Evermin medication, insulin for his diabetes, or a number of medical supplies he needs.

Jordan barely leaves his room. His mother describes him as a loner. He doesn’t play with other children. He doesn’t go to school; he is taught by a teacher who comes to his house. Instead, he listens to music, paints, sews, and plays with his mother’s phone. “I am desperate, hurt, helpless,” Solano says in a virtual interview, during which her son remains in the room. Jordan will only go out at lunchtime.

Jordan is one of the five medical cases that Cuban activists submitted last September 19 to the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF). They are demanding that the UN agency issue a finding on the situation of the many children who cannot receive care in the island’s hospitals.

For years, the country sold itself to the world as a medical powerhouse, but Cuba has long been in a health crisis that has only worsened in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, just as other sectors of the economy and life in general have deteriorated. Even as the sick, the hospitalized and occasional patients complained about the lack of medicines, the shortage of hospital beds and the few ambulances, the government continued to claim that the island was a medical powerhouse.

Now, the problem is not only the lack of medicine in pharmacies, but the lack of medical personnel in a country that has reported an exodus of over 300,000 Cubans in just two years. According to the National Statistics and Information Office (ONEI), some 12,000 doctors left the Cuban public health system last year.

“They don’t say it, but there are no doctors in Cuba; they don’t want to acknowledge it,” Cuban doctor Lucio Enriquez Nodarse, a member of the Free Cuban Medical Guild, says from Spain. “It is a more serious issue than anyone imagines. They are never going to say that the great Cuban medical school, the great [medical] powerhouse, has no doctors.”

This year, during a meeting Prime Minister Manuel Marrero Cruz only acknowledged that “the lack of foreign currency income” prevented “the acquisition of resources to meet the health needs” of the population. In other words, the government can hardly take care of its sick citizens.

Cuba has a population of 11.2 million inhabitants and 2.3 million of them are under 18 years of age. According to the 2022 Health Statistical Yearbook, the main causes of death among minors are malignant tumors, septicemia, accidents, congenital malformations, deformities and chromosomal anomalies. While the total number of children who are being neglected by the Cuban health system is unknown, every day there are numerous complaints about this situation from parents on social media.

For years, Yurislay Leyva Vasconcelo, Yurisay Marín Leyva’s mother, has been demanding a better quality of life for her daughter. Now 22 years old, Yurisay was born with achondroplasia (bone growth disorder) and congenital glaucoma, and she also suffers from epilepsy, hypertension and drug-induced gastritis.

“She never has the medicines she needs, because when she doesn’t lack one, she lacks another, and for a year nothing has been coming into the pharmacy,” says the mother of Yurisay, one of the cases presented to UNICEF.

9-year-old Geobel Damir Ortiz Ramírez is another of the cases submitted to the UN agency. Geobel has been diagnosed with a plexiform neurofibroma in his right eye, among other diseases.

“My son has a chronic condition and in Cuba there are no options for surgery or treatment for him,” says his mother, Eliannis Ramirez Baez. “I have even reported the situation to MINSAP. I have asked for help everywhere and no one will lift a finger to do anything. I am desperate, anguished, sometimes depressed, weak, because everything in this country is fruitless.”

Another case is that of 8-year-old Yoahira Lía Zulueta Jorge, who has infantile cerebral palsy (ICP), as well as epilepsy, diabetes, asthma and cleft palate. Her mother has not only asked for help for her healthcare, but also for the housing conditions in which she lives: “The house is at risk of collapse. I have gone to all the agencies and nothing [happened], they just tell me that there are no funds,” she says.

The fifth case, Cristofer Antonio Olivera, 4, has been waiting for an operation for almost his entire life. When he was 1 year old and just learning to walk, he accidentally took caustic soda (lye), which permanently damaged his gastric tube. The doctors have told his grandmother that there are not enough supplies to operate on him; in the meantime, Cristofer is fed with a syringe and a tube connected to his stomach.

Like the rest of the aforementioned parents, Cristofer’s caregivers are requesting humanitarian visas so they can leave the island and care for their children in other countries. Activist Avana de la Torre, who went to the UNICEF offices in Madrid, has since documented the cases of 1000 other minors unprotected by the Cuban government.

“This is a cry from the mothers and grandmothers of vulnerable children in Cuba,” she says. “This situation is probably not going to change anything, other than exposing the Cuban government and UNICEF.”

In early October, UNICEF regional director for Latin America and the Caribbean Garry Conille visited the island and met with President Miguel Díaz-Canel. After the tour, he said that “the current situation in Cuba creates limitations on the development prospects of children and adolescents, and he reiterated his agency’s commitment to “helping close the gaps to meet the needs of the most vulnerable children, adolescents and families.” According to its 2022 annual report, UNICEF gave the island $2.5 million from public donors, but the organization has acknowledged that “some nutritional deficiencies” affecting minors persist in the country.

The UNICEF office in Havana has not responded to activists’ complaints and calls. In a statement to EL PAÍS, Sendai Zea, the agency’s press officer said that “UNICEF shares the concern about how the situations of children, adolescents and families has deteriorated due to the prolonged economic crisis in Cuba, which affects their access to the goods and services necessary for their well-being and development.” Although Zea mentioned some of the programs and areas in which UNICEF works in Cuba, the press officer avoided commenting on the cases of children whose lives are in danger due to the lack of medical personnel and supplies.

While the affected children and their families wait for answers, Dr. Enriquez Nodarse is not optimistic about the situation: “I don’t think anything is going to happen with these children, because what is going to save the children is not people sending them a band-aid, a mattress, or a wheelchair,” he says. “The only thing that is going to save the children is for the dictatorship to end. There is no short-term solution.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition