The Jewish Holocaust survivor who hid in the depths of Nazi terror

The book of memoirs ‘Underground in Berlin’ tells the unusual story of Marie Jalowicz, who defied the Third Reich without leaving Berlin, circumventing the Gestapo and enduring rape, freezing conditions and hunger

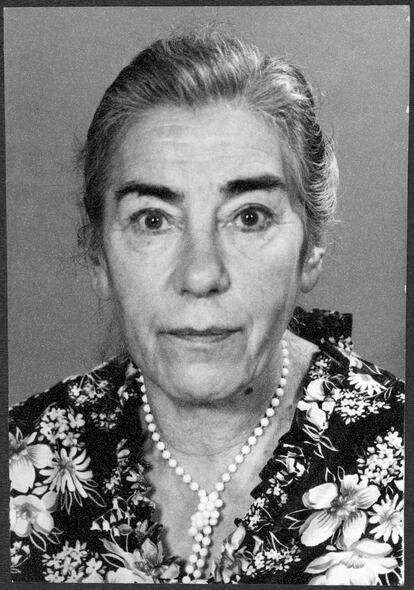

Marie Jalowicz, a Jewish Berliner who was 11 years old when Adolf Hitler rose to power in 1933, had never recounted her Holocaust survival story. After the war she enrolled in university, got married and had two children, and had a successful academic career as a professor of philosophy at the Humboldt University in Berlin. For fifty years she sparingly divulged any details to her family.

When she was in her 70s, one day her son Hermann placed a tape recorder on the dining room table without warning and Marie began to recount her story. In chronological order, she spoke of her memories, those of a teenager who endured hardship as a forced laborer at Siemens, escaping the wrath of the Gestapo, offering her body in exchange for shelter, suffering from the cold and hunger. Ultimately, she was trying to survive clandestinely in the heart of Berlin, the hub of the terrifying Third Reich regime, up until 1945, when the Allies defeated Nazi Germany.

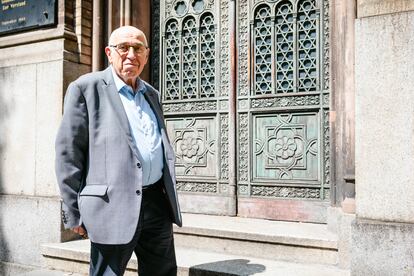

“I didn’t know how she would react. She was a difficult woman to handle, there was a ‘yes’ or ‘no,’ in between there was nothing. I told her that I had always wanted to tell her story. And she surprised me by asking, ‘Where do I start?’ I told her ‘from the beginning,’ and she did,” recalls her son, Hermann Simon, now a 74-year-old historian. Those sessions, which began on December 26, 1997, produced 77 cassettes (900 transcribed pages), hours and hours of recordings that Jalowicz took as if it were a comprehensive master class. “They lasted 60 or 90 minutes, and had a beginning and an end. You only get to do something like that once in a lifetime,” says Simon, who is still in awe, in a coffee shop in the Prenzlauer Berg district, very close to the New Synagogue in Berlin.

The last of the tapes was recorded in the hospital, a few days before Jalowicz’s death in 1998. This gave her time to chronicle the incredible story of how a 19-year-old girl in 1941 resolved to survive and attempted to do so by hiding in the wolf’s den of Nazi terror. Simon spent 15 years working on the contents of the tapes. He verified names, dates, places and facts. He is still astounded by the accuracy of his mother’s account, how she was able to retain all the information for decades with only her memory to rely on.

When Jalowicz’s story first saw the light of day in Germany in 2014, it blew away critics and readers. Many survivor accounts had been published, but none like this one. None of them could match the story of how a young Jewish girl had gone into hiding and managed not to be discovered in Berlin until the end of the war. This dispassionate, raw style, with no willingness to be stylistic, but purely documentary, was not customary, which above all, as Simon stresses, was “so honest.”

The shortened and edited version of Jalowicz’s recordings, put together with the help of the author Irene Stratenwerth, spares no details whatsoever, not even the most intimate ones. “We did not want to leave anything out,” confirms the historian. Her memoirs are entitled Underground in Berlin.

Jalowicz’s story is primarily a tale of survival. The daughter of an educated middle-class family, at the age of 15 she lost her mother to cancer and at 17 she was recruited as a forced laborer in a Siemens factory. There she participated in small production sabotages together with other workers and supervisors, and for the first time described how many Germans opposed the Nazis. In the story, there are no good guys or bad guys, but people with different ambiguities who behave well or badly depending on the circumstances. She recounts what the German foreman Max Schulz told them: “My parish priest says that the Nazis are the biggest criminals in the history of mankind.”

In 1941, plagued by antisemitic restrictions, Marie’s father passed away and she decided to leave the factory. She asked her boss to let her go. She knew, or sensed, that the persecution of the Jews could only get worse. “Why do you want to leave here?” she was asked. “I want to save myself,” responded Jalowicz. “What do you intend to do alone? Out there alone on the frozen wasteland.” “I prefer the frozen wasteland and I prefer to be alone because I can see where this is all going to end. They will deport us, and that will be the end for all of us.” More than 160,000 Jews were living in Berlin in 1933; by the end of the war, only 5,100 remained, according to the book Jews in Berlin, co-edited by Simon.

Marie’s ordeal crossed a point of no return in June 1942, when she escaped from a Gestapo couple who were going to arrest her and she went into hiding. She removed her yellow star and remained below the surface of everyday life in the big city, with the constant fear of being discovered while hiding in the dark. In the three years she spent in hiding from the Nazi authorities, she moved house almost 20 times. Communists, trade unionists, opponents of the regime, and even fanatical Nazis took her in or helped her. Some knew who she was, others had suspicions. Those Nazis, who boasted of being able to spot a Jew from a distance, were also fooled.

Through these experiences, Jalowicz’s reflections paint a vivid picture of Berlin’s diverse society under Nazi rule. Not only of the merchants, doctors and intellectuals who comprised her immediate environment, but also of workers, domestic servants, immigrants and social outcasts. Unlike other clandestine individuals, such as Anne Frank, the young Jalowicz was constantly on the move in the city. She took public transportation, walked, waited in rationing queues for those who sheltered her.

On one occasion, while waiting for a new place to sleep, she was forced to spend the night out wandering around Berlin. And when her physiological needs called, she describes how she snuck into a small bourgeois building in the southeast of the city. “When I found a plaque with a name that I disliked and that sounded Nazi-like, I squatted down and did my business. What would those people think when they discovered the little gift on the doormat in the morning?”

The importance of fortune

Her memories evoke moments of sheer rawness, such as when she is forced to offer her body to protect herself. She recounts it like a person describing what she had for breakfast in the morning. She equally does not sidestep the widespread rape depicted in A Woman in Berlin, the chilling anonymous text that recounts how women became victims of the Soviet troops who entered Berlin at the end of World War II. “It happened to me too, of course… I was visited at night by a stocky, friendly guy named Ivan Dedoborez. I didn’t care much for him. Then he wrote a note in pencil and left it on my door: that was his girlfriend over there and I should be left alone. And afterward they never bothered me again.”

Her determination and willpower compelled her to salvation, but Jalowicz always stressed the importance of pure luck, as she recalled in a 1993 speech. “The survival of each individual who remained in hiding was built on a concatenation of events that is often beyond belief and can be called miraculous.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition