The abyss of child sexual exploitation in Bolivia: ‘They told me that if I continued looking for my daughter, I was going to die’

Relatives of missing girls and women denounce the lack of investigations and the limited number of convictions. NGOs are working to rescue victims, while the government is attempting to strengthen the police and judicial bodies to combat this widespread crime

A man in a suit. A boy in a cap and shorts. A man in overalls. An elderly man. Two young men in jeans. Another with a tie, briefcase still in hand. One after another, in less than a minute — the time it takes for the traffic light to change — 18 men enter a building with a red facade.

This is the 12 de Octubre district of the Bolivian city of El Alto. A guard stands at the door. Inside, there are wall-mounted urinals right near the front, where visitors can make a brief stop. What lies beyond the bathrooms cannot be seen, but everyone knows what’s there: rooms where pimps are engaged in the prostitution of (mainly) women and girls.

On a Monday afternoon, the red light district is already filled with prostitutes, no matter where you look. “From Thursday to Sunday, there are even more people,” explains a worker from the Munasim Kullakita Foundation — which means “I love you, little sister,” in Aymara, a major Indigenous language — a Bolivian NGO that combats human-trafficking and the commercialized sexual exploitation of minors.

Prostitution — when carried out voluntarily by people of legal age — isn’t a crime in Bolivia. However, the activity of prostituting another person for profit — otherwise known as “pimping” — is. Queen criticizes this concept of “voluntary” prostitution, because it ignores the vulnerability of the person who engages in this activity. The conditioning serves, in practice, to protect it. For this reason, organizations like hers focus on what’s clearly illegal: sexual exploitation of minors for profit. “Consent never exists in these cases,” she points out.

“It’s a [widespread] phenomenon and there’s a lot of ignorance surrounding it, both about its dynamics and the spaces in which it develops,” says Nancy Alé, coordinator of the Protejeres-Tejiendo Redes Seguras (“weaving safe networks”) program for the prevention of sexual violence against minors. It was developed by the NGO Educo, alongside the Munasim Kullakita Foundation and other organizations. Sexual exploitation can “materialize in the form of human-trafficking, pimping, commercial sexual violence, or pornography,” Alé adds.

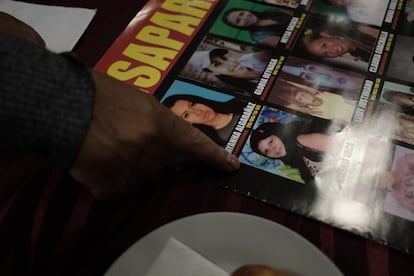

In the cities of El Alto and La Paz, the walls of train stations, buses and the airport are covered with posters that show faces of missing people. There are also screens, where images and information of missing women and girls are displayed. Their families continue to search for them.

The lack of data complicates the ability to determine how this violence comes about. According to the latest figures from the government of Bolivia, in 2022, there were 711 complaints filed regarding human-trafficking and related crimes (including child pornography, pimping and commercial sexual exploitation), in which 23% of the victims were minors. All the experts consulted emphasize that these figures are only the tip of the iceberg: it’s not known exactly, for example, how many girls and women are still missing, or how many minors are exploited without their families coming forward to report abuse.

According to preliminary data from the Ministry of Government, in 2023 alone, the disappearance of 3,409 people was reported. Of these, “485 remain missing,” as confirmed in a telephone interview by Carola Arraya, general director of Bolivia’s Office Against Human Trafficking. Meanwhile, a 2019 investigation by the Munasim Kullakita Foundation identified 338 cases of commercial sexual exploitation of minors that year.

“She probably went off with her boyfriend”

“Much of the discourse — even from the authorities — [claims] that 15-year-old girls work [as prostitutes] because they want to,” Alé laments. This misogynistic prejudice affects the lack of investigation, because it’s common, she explains, that — when a young woman disappears — a police officer will say, “she probably went off with her boyfriend.”

Ricardo rescued his 16-year-old daughter from a brothel in the city of Santa Cruz — in an area similar to the 12 de Octubre district of El Alto — two weeks after her disappearance. The girl — deceived by a friend — was kidnapped in La Paz, held prisoner for several days and finally transferred to the economic capital of the country, according to the testimony that EL PAÍS has had access to. “They found her drugged, but they were able to save her thanks to a police operation,” says a person close to the victim.

Lidia, however, wasn’t so fortunate. Her daughter, Juliva, left home on July 10, 2014, on her way to the Public University of El Alto, where she was studying Psychology. She was in her second year. She never came back.

“We reported it in La Paz… but since my daughter was already 21-years-old, they didn’t pay any attention to us, they told me that she had gone off with some man,” she recalls, from a hotel in the Bolivia capital. She holds a stack of flyers that she still distributes: they show a photo of Juliva and some of her information.

During the first 15 days after her disappearance, Lidia received several calls from Juliva’s number. Whenever she would reply, there would be no answer. One of her other daughters also received a call: a man’s voice told her that the young woman was in the city of Oruro — in the west of the country — and that she needed clothes to be brought to her.

“The police never traced the calls, they didn’t analyze them,” Doña Lidia cries. She says that, over the years, her daughter’s case has been assigned to “10 different investigators.” One of them, she says, even asked Lidia for money to look for her daughter. “I gave him half of [what he wanted]... but he never did anything.” The last possible clue about her daughter was obtained in 2015. “A man called me from a number that I didn’t know and told me that he had seen my daughter in Cochabamba. So, I went there. But I didn’t find her,” she laments. It was around then that she went to a media outlet to request help in the search for Juliva and — upon leaving the office — she got a call:

“They told me that if I continued looking for my daughter, I was going to die.” The police — according to Lidia — never investigated these threatening calls. “I think it’s because we’re poor people. The same doesn’t happen with rich people,” she affirms.

Lorenza — who expresses herself in Spanish mixed with Aymara words — also hasn’t managed to find her daughter, Juliana. She was 12-years-old when she disappeared, on July 14, 2016. “She had gone to play at my eldest son’s house, but she never arrived,” the woman remembers. She speculates that “they must have kidnapped her.” Shortly after that — like what occurred with Lidia — she received a call from a man who assured her that he would return her daughter, but only if she gave him money. “I waited at the [location] they gave me, but there was nobody there. They called me again to ask for more money.” Lorenza didn’t have the amount. She was never contacted again.

A weak police response

Not knowing the fate of their daughters, Lidia and Lorenza agree to speak with EL PAÍS with the hope that their daughters — if they’re still alive — will read the story and know that their mothers are still looking for them. But “mapping the places where sexual exploitation occurs is very difficult, because the police are very weak in Bolivia,” Alé explains. Queen confirms this. “I once notified the police when we knew that there were minors in a brothel. When they showed up, there was no one [in the building],” the social worker says. She suspects that the police tip off the pimps.

“We have a weakness in the judicial system and in [the investigative process],” Arraya agrees. For this reason, she assures this newspaper, the administration of President Luis Arce is “strengthening the specialization and training of public servants, both from the judicial bodies and the Bolivian police” because the crime “of human trafficking and its related crimes (pornography, pimping and commercialized sexual violence)” are “complicated crimes” for officials who don’t have adequate experience and training.

According to the latest report on human-trafficking from the US Department of State — which dedicates a section to Bolivia — “the government of Bolivia does not fully meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking but is making significant efforts to do so.” Regarding the police efforts, the same document notes that the government “did not report investigating, prosecuting, or convicting traffickers and did not report identifying or referring victims to care” in 2022, the last year that the agency has detailed figures from. By contrast, in 2021, “officials reported 62 trafficking investigations, 22 trafficking prosecutions (12 for sex trafficking, five for labor trafficking, and five for other forms of servitude) and 12 trafficking convictions.” This is just the tip of the iceberg, according to Alé.

There are several places in Bolivia where sexual exploitation is evident. “Around [certain areas], a commercial environment is also created,” Alé describes, giving logging or gold mining sites as examples. “Specifically, where a men’s camp arises,” she specifies. This is what happens in the 12 de Octubre district, where hundreds of shops and fast-food places are located. Men come out, carrying food and drinks. “Why doesn’t anyone question the presence of teenagers in places like these?” the Educo expert asks.

From the department against human-trafficking, Arraya insists on the effectiveness of the measures that are being applied to strengthen judicial investigations. New technology and equipment are being provided to officers to prosecute online child pornography cases, while facial recognition systems have been purchased by the state to locate missing women and girls. A cost-free university degree that specializes in countering human-trafficking has been created, while agents are being trained to more effectively observe airports, bus terminals and border crossings. There has also been an intensification of research in mining areas. Likewise, educational prevention programs have been created in schools, while the government of Bolivia has signed agreements with Brazil and Argentina to monitor crimes committed in border areas.

President Arce’s administration plans to modify Law 2/63 on Trafficking and Human-Trafficking, to classify crimes more precisely and include new ones, such as online grooming (when an adult impersonates a minor on the internet to establish a relationship of trust with a child or teenager), or the dissemination of “child sexual material” on social media.

The vulnerability of victims

“Of the 3,409 people who disappeared in 2023, in 2,193 cases, the person had behavioral or family problems, which makes them [more likely to be] potential victims of trafficking,” explains the general director of the department that investigates this crime. Child recruiters often take advantage of victims’ vulnerable situations, according to organizations that work with victims. The most common techniques are false job offers, or what Alé calls the “infatuation technique” (or the “loverboy technique”), which consists of the captor courting a teenager until he overrides her will and sexually abuses her, or prostitutes her.

Online recruitment — through mobile applications or social media — is increasingly present, as confirmed by Arraya. “And even [through] online video games,” confirms Lindsay, a teenage member of the Consultative Council of Children and Adolescents of La Paz and El Alto, formed to fight against the online recruitment of minors into the sex trade. “I’ve seen how some of my friends compete to see who receives the most [follows] from unknown people [on their social media], as if it were proof of the success of their publications,” adds Milenka, a member of the same group.

Monica (not her real name) is a 26-year-old survivor of sexual abuse. She was a victim of the loverboy technique. After suffering years of abuse from her father — who subjected her to beatings and rape — she ended up staying in the home of her godfather and his wife when she was still a teenager. “He started to talk to me, [saying] that he was in love with me, that he was going to take me to another house so we could be alone… at that age, they brainwash us and they can dominate us,” she remembers. “When an older person dominates a minor and offers them a house or money in exchange for sex, that’s called pimping,” Queen replies. She highlights one of the main problems in identifying this form of sexual violence: “Girls — in an attempt to survive — validate what they’re experiencing, as if they’re doing it voluntarily,” she emphasizes. Part of society also validates it, she adds.

Today, Mónica — who was welcomed in a house run by the Protejeres program, when she wasn’t even 18-years-old — has rebuilt her life. She has two children and has just finished her degree in Social Work. “Although I’ve had setbacks during the process,” she regrets.

“Pimps are experts at detecting vulnerabilities,” says Queen, as she points to two men standing in one of the main squares of the 12 de Octubre district. She doesn’t know their names, but her years of experience working in the area give her a clue. “Look, since we arrived, they haven’t moved. Do you know why? Because they’re looking to pick up a young girl.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

More information