The scourge of the selfie

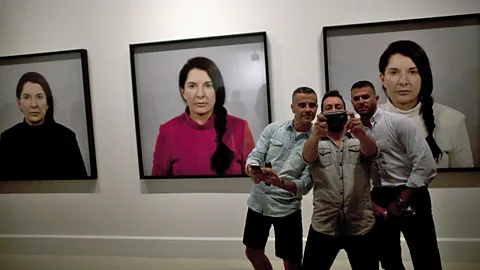

Museum visitors now turn away from works of art to snap photos of themselves. Jason Farago investigates this invasive trend.

I had a look at Instagram on a random Monday at 5:30pm, just as the Museum of Modern Art in New York closed for the day. The number of photos posted from the museum that day was more than 300 – and that figure counts only those images affixed with MoMA’s geotag, and thus could be a grave underestimate. What were these photos depicting? Paintings, of course, especially Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night and Ed Ruscha’s Oof, whose titular onomatopoeia is a fan favorite. Not only art, though. A lot of people seem to like taking photos of wall text, and five museumgoers, bizarrely, posted photographs of their tickets.

But more and more, the view at MoMA is a view of oneself. Starry Night and Claude Monet’s Water Lilies are the prime selfie real estate, it seems, though two friends posted four different photos of themselves and had killer taste in backgrounds, posing in front of two cut-outs by Matisse, Andy Warhol’s cow wallpaper and the young painter Matt Connors’ monochromes, which are particularly flattering. (The hashtags were #nophotosallowed and #whoops.) One woman, clad in all black from her hijab to her skirt, struck a pose in front of a Joseph Kosuth painting that matched her outfit. People posted selfies from the lobby, the windows and the garden, often tagged with references to their clothes. At least two people posted photos of themselves from the bathrooms, though Marcel Duchamp’s urinal on the fifth floor had no selfie takers.

Maybe someone else will have fun writing a counterintuitive essay about how the museum selfie represents some secret opportunity: that endless narcissistic portraiture in fact disguises some grand creative act. But this is not going to be that essay. Selfies are, let’s face it, the newest scourge of the art museum – and they are not going away, as confirmed by this week’s Museum Selfie Day (really). If you have problems with that, and heaven knows I do, you’ll have to take it up with a bigger authority than the guardians of our art museums, who one by one are giving up on no-photograph policies. The National Gallery in London finally did away with their prohibition last summer, prompting the Guardian writer Zoe Williams to tear through the museum and snap herself with Rembrandt and Vermeer.

Close-up

Photography in museums has become so invasive that, in no-photos-allowed museums like New York’s Frick Collection, I watch museum guards spending almost the entirety of their shifts not supervising the art, but dissuading people from taking pictures. (And pity the guards in those few German museums that make visitors pay extra for the right to take photographs: I was not the only person to get yelled at during my last visit to the Schloss Sanssouci in Potsdam.) But two coincident developments at the end of the last decade combined to make the museum into selfie central. One, of course, was the rise of social media and in particular Instagram, which not only allow for quick distribution but also for immediate, uncomplicated praise in the form of ego-sustaining ‘likes’. The other development – subtler but more important – was the introduction of a second, front-facing lens on cameraphones, allowing users to see their own image as they pose. Stand in front of the Mona Lisa at the Louvre or Starry Night at MoMA, and you’ll now see a good number of visitors looking away from the painting, more interested in themselves on screen.

This poses a real challenge to curators and artists, I’d argue, who increasingly have to reckon with exhibition design that takes into account new, probably not better ways of moving among artworks. On a recent visit to the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum in New York, I stood in a gallery filled with kinetic sculpture from the 1960s with, by my count, 12 other museumgoers – and every single one was looking at his or her phone. The cameraphone, and the portal it offers away from the museum and into what we used to call cyberspace, is not a phenomenon that can be taken lightly. It challenges the most basic conceptions of how viewers experience art, and what demands the museum places upon them.

After all, one of the reasons so many people bridle at the museum selfie is because we still conceive of the museum – rightly or wrongly – as a place of learning and self-improvement. That has not always been the case; the early Wunderkammer, or 'cabinets of curiosities', were more displays of beauty (and wealth) than educational efforts. It was the 19th Century that gave us the museum as a site of moral improvement, notably in Britain: as the scholar Amy Woodson-Boulton has shown, “reformers” constructed museums in Birmingham, Liverpool and Manchester not just to showcase the wonders of art and science, but to acculturate working-class populations to middle-class forms of behaviour. And museums today still have a disciplinary character: don’t touch. Don’t talk too loudly. No skateboarding down the Guggenheim’s ramp.

See and be seen

Yet museums in the 19th Century, especially in continental Europe, were also already places for self-presentation – for showcasing yourself alongside artworks as something to look at. Parisians dressed up to go to the Louvre, and gossip columnists would report on the fashions of visitors to the salons. Museums, like other public entertainments such as pleasure gardens and fairgrounds, were places to be seen as much as to see, and that remains true today. Many of today’s museum selfies, whether they’re snapped next to Autumn Rhythm or in the bathroom mirror, are as much about status as appearance. I was here, they say, and in MoMA’s case they might even be saying: I paid $25 for admission.

Increasingly for museums and curators, selfies are simply a reality, to be designed for and considered rather than dismissed. It is easy for supercilious critics to grouse that museum selfies are inane. The harder, and more pressing, task is to accept that people see art as selfie backgrounds, and to engage with the difficult questions that phenomenon engenders for artists and their advocates. This past summer, the gifted American artist Kara Walker presented an astounding sculpture made of sugar, in the form of a nude black woman with exaggerated lips, breasts and buttocks. If for many visitors it was a painful evocation of slavery, other gallery-goers, white and black alike, took the opportunity to make lewd gestures for their cameras, and then post them online.

When I saw Walker’s sculpture, on a brutally hot summer day, I wondered whether the artist had erred in imagining that her art would stay put in the space of the gallery, and not circulate in remixed and reconstituted forms. But Walker was watching – and, in a critical but not judgmental film she screened last December, she followed her own audience to see how they beheld her sculpture, why they photographed themselves with it and whether their poses perpetuated the objectification her art is meant to denounce. If the museum selfie represents a recession of art from an autonomous position to a backdrop or a prop, then artists and curators are going to have to start thinking like Walker – and to consider just what power art can retain in such new circumstances. Otherwise we are going to be stuck with a lot of duckface self-portraits in our Instagram feeds, with half-obscured masterpieces peeking from behind.