/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/46056002/Damimpact_SouthAmerica.0.0.jpg)

Human beings have replaced nature as the dominant force shaping Earth. We've cleared away forests, dammed up mighty rivers, paved vast roads, and transported thousands of species around the world. "To a large extent," two scientists wrote in 2015, "the future of the only place where life is known to exist is being determined by the actions of humans."

So what does this look like? In recent decades, NASA has been tracking the major transformations we've wrought via satellite. In its "Images of Change" series, the agency has posted a number of before-and-after images showing the exact same rainforest or glacier or city years or decades apart. The differences are often breathtaking. Here are 14 of the most revealing changes:

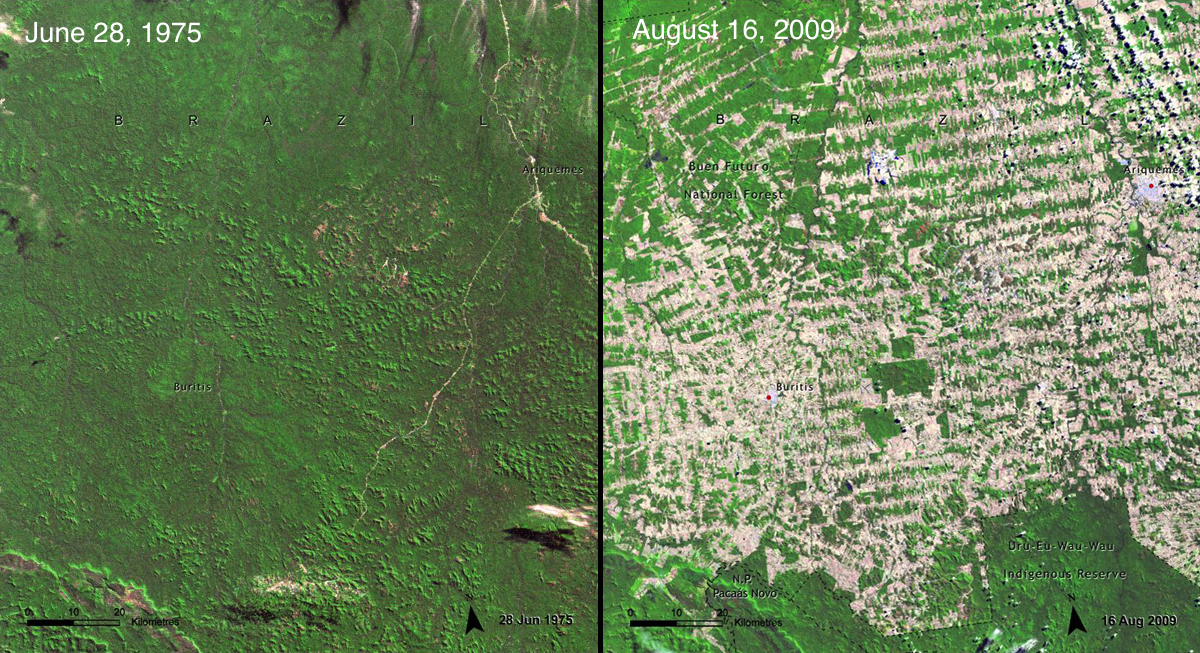

1) Rainforests get swallowed by farms in Brazil

Satellite images of Rondônia in western Brazil, taken in 1975 (left) and 2009 (right). (NASA, Images of Change)

Humans have been clearing forests to make way for farms and pastures for at least 7,000 years. And as the world's population soars past 7 billion, the pressure for cropland is only growing.

The image above shows the state of Rondônia in western Brazil, one of the most deforested parts of the Amazon. In 1978, 2 percent of the state's rainforest had been cleared. By 2008, that was up to 34 percent — an area the size of West Virginia. You can see a more detailed progression in these images: New roads protrude into the forests like fishbones, with nearby trees vanishing soon after. The newly cleared land can only sustain crops for a few years until heavy rains erode the soil, at which point it's turned over for cattle. Then repeat.

Deforestation has all sorts of troubling side effects, from shrinking habitats for forest species to increased global warming via a reduction in carbon dioxide–absorbing trees. Brazil has tried to protect its rainforests in the past decade, but pressure to clear away trees has risen again since 2013.

2) Cancún expands at a stunning rate

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3577082/Cancun_1200x648.0.jpg)

Cancún, Mexico, seen in 1979 and 2009. (NASA, Images of Change)

Cities and towns have been around for thousands of years, but the growth of urbanization has been astonishing over the past century. More than 3.9 billion people and counting now live in urban areas.

The images above show the rapid growth of Cancún, Mexico. In the 1970s, this area was lightly inhabited, home to artisanal fishermen and empty beaches. But the government pushed to turn the area into a tourist hotspot, and today it's home to 722,000 people. That's been a huge economic boon, though it's also meant a loss of biodiversity and polluted water. The fact that more people now live on Mexico's coast also increases their vulnerability to hurricanes — one reason why the cost of natural disasters keeps rising worldwide.

3) Dubai builds a chain of artificial islands

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3578930/Dubai_Islands_1920x1200.0.jpg)

Dubai, United Arab Emirates, seen in 2001 and 2011. (USGS and NASA)

Some cities have gotten creative about urban growth, reclaiming land from the sea. These images show the rapid growth of Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates, between 2000 and 2011.

To promote beach tourism, the city built hundreds of artificial islands along the coast using sand dredged from the seashore. Rocky barriers were put in place to protect them from erosion. The two most famous islands are shaped like palm trees. As the images above show, the growth of Dubai on land has been no less dramatic, with barren desert replaced by irrigated land and roads.

4) The oil sands boom in Alberta, Canada

Open pit mines near Fort McMurray in Alberta, Canada, seen in 2000 and 2007. (NASA, Images of Change)

In the 2000s, global demand for oil kept surging, but conventional wells weren't keeping up. So companies cast an eye on the vast oil sands buried beneath the boreal forests in Alberta, Canada. These sands contain bitumen, a gooey petroleum that can be extracted for fuel.

The images above show the growth of oil sands mining near the Athabasca River during the 2000s. Once the sand is mined, it's rinsed with hot water to separate out the bitumen. The sand and water are then dumped in tailings ponds, which can be seen as smooth tan squares in the images.

These mines have had a profound impact on the landscape around them. Forests have to be cleared to make way for the mines — more than 256 square miles as of 2011. The tailings ponds themselves can be toxic to birds. As such, Canada's regulators have required companies to restore the land after they finish mining. Another NASA satellite photo here shows a reclaimed area after a pond was drained and planted over, though the grasses have not yet grown.

Meanwhile, because it takes so much energy to extract oil from the sands, this type of fuel is worse for global warming than regular crude oil. That's a big reason the Keystone XL pipeline, which would help bring Alberta's oil to market, has been so controversial in the United States.

5) Ukraine's landscape recovers after Chernobyl

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3577176/Landrecovery_Ukraine.0.jpg)

Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, seen in 1986 and 2011. (NASA, Images of Change)

Human activity doesn't always expand relentlessly. Occasionally, nature reclaims the land. The images above show the evolution of the area around the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant after a reactor explosion in 1986.

On the left, you see the area in 1986, just before the accident. There are cultivated fields (in light colors), small towns (in blue and purple), and old forests (dark green). Then on April 26, radiation began leaking out of Chernobyl's reactor number four and people fled the area.

As of 2011, things look very different. The abandoned towns are decaying. The farms have now reverted to grasslands (bright green). The forests were bulldozed by the government and replanted (younger trees are seen as lighter green). Intriguingly, plant and animal populations have actually grown within the exclusion zone since the accident. Animals are still adversely affected by the radiation, but they are also thriving in the absence of humans.

6) A manmade fire rages in Namibia

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3578968/etosha_composite.0.png)

Etosha National Park in Namibia. The white area is the Etosha Pan, a salt-encrusted lake bottom. The dark brown area shows where a fire burned in June 2012. (NASA, World of Change)

For much of the 20th century, as human settlements expanded, we thought we knew how to deal with large-scale wildfires: Prevent them at all costs. The US Forest Service adopted this strategy in the forests of the American West. And Namibia's forest managers used this strategy in Etosha National Park, which opened in 1907 and serves as a key reserve for rhinos, elephants, and lions.

This turned out to be a bad idea. Wildfires were a crucial part of the ecosystem. Before humans came along, Namibia's savannas would burn about once per decade. When park managers suppressed these periodic wildfires, that only led to really massive fires later, as vegetation built up.

So now, in Namibia, the park managers periodically try to set smaller fires themselves. Occasionally, though, these fires can get out of hand, as happened in June 2012, shown by the satellite image above. On June 9 and 10, winds picked up, and the fire rapidly spread west. Fortunately, no animals were harmed — in contrast to an out-of-control fire in 2011 that killed 30 rhinos.

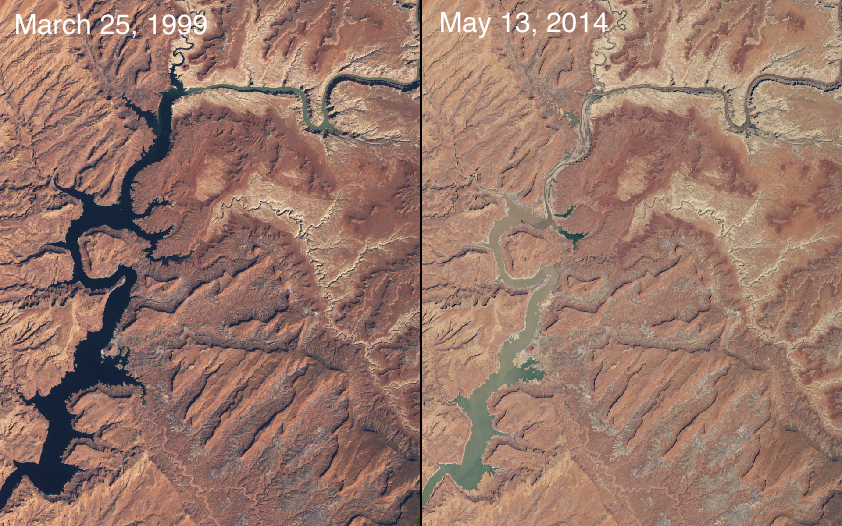

7) Efforts to tame the Colorado River hit a snag

Lake Powell, seen on March 25, 1999, and May 13, 2014. (NASA, Images of Change)

The Colorado River begins in the Rocky Mountains and courses through the American Southwest. During the 20th century, Americans built a complex system of dams and reservoirs to tame the river, providing a steady source of fresh water for farms and cities like Phoenix and Las Vegas. Water from the river is divvied up among states under an elaborate set of rules.

But we can't entirely control nature. The images above show Lake Powell, a reservoir on the border of Arizona and Utah that was created after the construction of the Glen Canyon Dam. Back in 1999, the lake was filled high, with plenty of water for nearby counties. But in the early 2000s a brutal drought arrived, and water levels began dropping. As of May 2014, the lake was only at 42 percent capacity.

The communities around the region have tried to adapt through efficiency and conservation. Still, some experts have argued that the Southwest is unprepared for future droughts — which are expected to become more frequent with global warming. That will raise the risk of shortages in reservoirs like Lake Powell.

8) The Aral Sea, once massive, nearly vanishes

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3578986/aral_sea_2000_vs_2012.0__1_.0.jpg)

The Aral Sea, seen in 2000 and 2014. (NASA, Images of Change)

The Aral Sea, tucked between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, was once the fourth-largest lake in the world. Today, after decades of being drained for irrigation, it's nearly gone.

What happened? In the 1960s, the Soviet Union diverted the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers that fed the lake — via a network of dams and canals — for use in cotton fields and other agriculture. The surrounding desert bloomed for a period, but it eventually led to disaster.

Here's NASA: "As the lake dried up, fisheries and the communities that depended on them collapsed. The increasingly salty water became polluted with fertilizer and pesticides. Blowing, salty dust from the exposed lakebed became a public health hazard and degraded the soil. Croplands had to be flushed with larger and larger volumes of river water."

By the 2000s, the Aral Sea was roughly 10 percent of its original size. The area's once-vital fishing industry had been eradicated, leaving entire communities unemployed.

9) Alaska's Columbia Glacier recedes rapidly

Alaska's Columbia Glacier, seen on July 28, 1986, and July 2, 2014. (NASA, Images of Change)

One of the most dramatic ways we're transforming the planet is through global warming. And a great place to see its effects is through the melting of glaciers and ice sheets around the world.

The images above show the Columbia Glacier in Alaska, which flows directly into the sea. The glacier had stayed more or less fixed in place between its discovery in 1794 and 1980, but then suddenly began shrinking. Between 1986 and 2014, its nose had retreated 12 miles north, making it one of the fastest-receding glaciers in the world.

NASA's Earth Observatory explains that the retreat of Columbia Glacier is only partly a result of warmer air and water temperatures: "Climate change may have given the Columbia an initial nudge off of the moraine, but what has accelerated its disintegration has more to do with mechanical processes than warming temperatures." Global warming is having a similar impact elsewhere: All told, the world's glaciers are now losing 226 gigatons of ice per year.

10) Antarctica's Larsen B ice shelf disintegrates

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3579020/larsen_b_composite.0.png)

Larsen-B ice shelf in Antarctica, seen on January 31, 2002 and February 17, 2002. (NASA, World of Change)

Receding glaciers are one thing. But the massive ice sheets atop Greenland and Antarctica are an even bigger deal. As the world keeps warming, these ice sheets are starting to melt into the ocean, a change that is expected to raise global sea levels significantly.

Scientists witnessed a dramatic example of this in 2002, when a huge chunk of the Larsen B ice shelf in Antarctica — an area of 1,250 square miles — simply disintegrated into the ocean in the span of a month. The collapse was precipitated by a series of unusually warm summers, which created melt ponds during the warmer months that acted as wedges, hastening the shelf's disintegration.

By itself, the collapse of an ice shelf won't raise global sea levels, since ice shelves are already floating in the sea. But those shelves do help contain the massive ice sheets on the land behind them, so when a shelf disintegrates, all that ice can flow to the sea more quickly. And that helps raise sea levels.

You can see that flow of land ice in these images after the collapse of Larsen B. And here's troubling news: Scientists have found that a number of Antarctica's other ice shelves are also rapidly thinning.

11) The US cleans up its air pollution

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3579034/Air_Pollution_1200x420__1_.0.jpg)

Images show concentrations of nitrogen dioxide in 2005 and 2011, from low (blue) to high (red). (NASA, Images of Change)

Not all the ways we're transforming the planet are negative. Here's some good news: Satellite data from NASA, shown above, revealed a huge reduction in nitrogen dioxide pollution from cars, trucks, and power plants in the United States between 2005 and 2011.

Nitrogen dioxide is produced when gasoline gets burned in cars or coal gets burned in power plants. It's been linked to a variety of respiratory problems, and can combine with other pollutants to form smog. It's also a good proxy for pollution more generally.

The EPA first began cracking down on nitrogen dioxide in 1971, and concentrations have fallen sharply over time. Power plant operators have installed scrubbers to remove pollutants from their smokestacks, and car manufacturers have adopted catalytic converters to curtail nitrogen oxides and other emissions. More recently, since 2005, many electric utilities have been switching from coal to natural gas in order to generate electricity.

12) Iraq's marshes recover after Saddam Hussein

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3579156/iraq_marsh_composite.0.png)

The wetlands of Mesopotamia in 2000 and 2006. The map shows standing irrigated crops (light green), standing water (dark blue), vegetation (dark green), and bare ground (brown). (NASA, World of Change)

Here's a change that actually restored nature — at least temporarily. During the 20th century, Iraq's lush wetlands between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers had mostly dried up because of a series of dams that had been constructed for electricity, as well as a deliberate strategy by Saddam Hussein to drain the wetlands and punish the region's Marsh Arabs for rebelling.

But as the images above show, things changed significantly after the second Gulf War. After the fall of Saddam Hussein, Iraqis tore down many of the canals that had drained the marshes. The wetlands were once again fed by the rivers in the spring, and vegetation had returned by 2006 — shown in dark green on the right-hand side. The UN found that the marshes were back up to around 58 percent of their historic levels, and native birds and fish were rebounding.

But it's not clear if the wetlands will survive in the future. NASA explains that new dams were being built upstream as of 2010. The fate of nature is, once again, largely in our hands.

13) The ozone layer thins — but then starts healing

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3577778/ozone_composite.0.png)

Sometimes it's possible to stop an environmental catastrophe before it's too late. Back in the 1970s, scientists first realized that we were rapidly depleting Earth's stratospheric ozone layer, which protects us from the sun's harmful ultraviolet rays. The culprit? Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) — chemicals that were widely used in refrigerators and air conditioners.

As the NASA images above show, between 1979 and 2013 these chemicals had chewed a massive "hole" in the ozone layer above Antarctica, and the damage was poised to spread further north. Without the ozone layer's protection, more and more people would be exposed to UV rays, and skin cancer rates in many places might have soared.

Happily, this apocalyptic scenario never came to pass. Scientists uncovered the problem in time. Under the 1987 Montreal Protocol, world leaders agreed to phase out CFCs, and eventually the hole in the ozone layer stopped expanding. In 2014, a UN assessment found that the ozone layer is just now starting to heal — and should be back to its 1980 levels by 2050 or so.

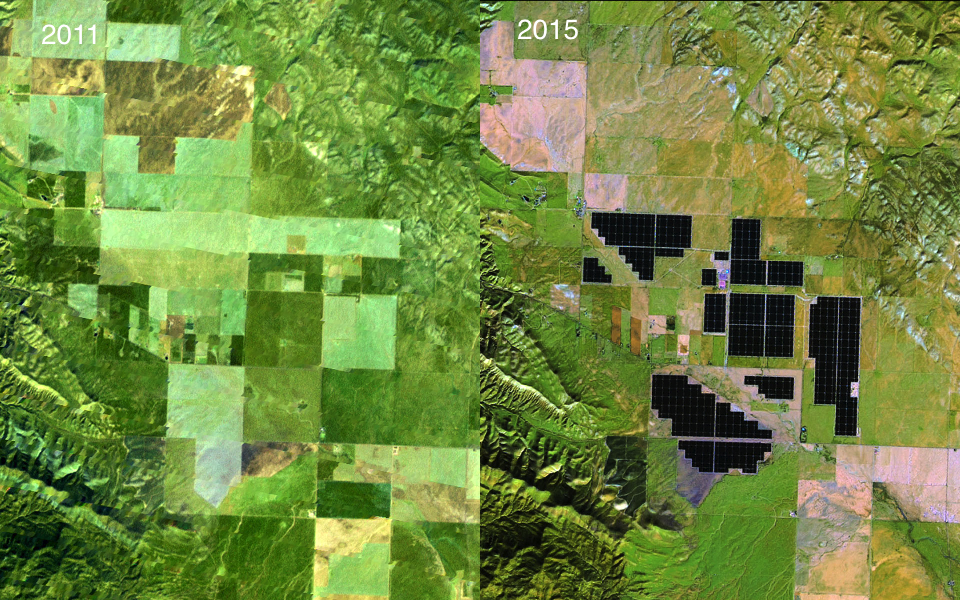

14) Solar farms sprout up in California

The Topaz Solar Farm in California, seen in 2011 and 2015. (NASA, World of Change)

The next big environmental challenge is global warming, which will likely prove much harder to stop than the hole in the ozone layer. It will entail revamping our entire energy system; switching away from fossil fuels like coal, oil, and natural gas; and seeking out cleaner sources.

Some places are already taking steps along those lines. The image above shows the growth of the Topaz Solar Farm in central California, a 550-megawatt plant consisting of 9 million panels across 9.5 square miles. It's a modest step in shifting the state toward cleaner energy.

Even so, some environmentalists have opposed the project, arguing that solar farms need a lot of land and fences, hindering the movement of the federally protected San Joaquin kit fox. It's a reminder that even efforts to reduce our environmental footprint in one area can lead to unexpected impacts elsewhere.

Further reading:

- A guide to the debate over when, exactly, the "Anthropocene" began

- We're damming up every last big river on Earth. Is that really a good idea?

- Deforestation in Brazil is rising again — after years of decline

- The oceans are acidifying at the fastest rate in 300 million years. How bad could it get?

- The world is on the brink of a mass extinction. Here's how to avoid that.