The Question That Will Decide the 2016 Election

Republican candidates need to address the concerns of millions of Americans terrified that they will lose their health insurance.

“Will you take away my health insurance?”

That question does not get asked often at Republican presidential forums. Yet it will be the most decisive question in the 2016 presidential election.

Since the last presidential election, the major provisions of the Affordable Care Act have taken effect. Millions of people are now enrolled in Medicaid, or are receiving health insurance subsidies through state exchanges, who were not enrolled or subsidized in November of 2012. Obamacare skeptics may disparage these benefits as inefficient, counter-productive, and excessively costly. Fine. Those who receive them won’t cherish them any less. The mortgage-interest deduction is not exactly a model of economic rationality. Try taking it away. Go ahead. Try.

Exact numbers of Obamacare beneficiaries are difficult to compute. However, healthcare economists estimate 11.2 million added to the Medicaid program since open enrollment under ACA began, and 10 million receiving subsidies through exchanges. And, since 2010, an estimated 5.7 million young adults between the ages of 19 and 25 gained coverage, mostly through their parents’ plans. If the ACA were repealed without a replacement, one would expect most or all of these people to lose their coverage.

Repeal of the ACA is the declared goal of all Republican presidential candidates. While most have some vision of replacement, that vision tends to be highly unspecific—and still likely to radically reduce the coverage Obamacare now provides.

Jeb Bush is probably the least fire-breathing opponent of the Affordable Care Act among the Republican candidates, as worried conservatives have anxiously noted. He consistently emphasizes “replacement” alongside “repeal.” But when he speaks in anything like detail, as he did in Iowa in March, this is what he says:

The effort by the state, by the government, ought to be to try to create catastrophic coverage, where ... if you have a hardship that goes way beyond your means of paying for it, that you have—the government is there or an entity is there to help you deal with that. The rest of it ought to be shifted back where individuals are empowered to make more decisions themselves.

That’s consensus conservative doctrine. Yet to a current ACA beneficiary it must sound ominous. “If you have a hardship that goes way beyond your means of paying for it …” Even small proposed changes in Medicare have up-ended American politics. Back in 1995, the government of the United States shut down for a total of 27 days over budget fights that included a disagreement over $11 per month in Medicare Part B premiums. That shutdown framed the election of 1996, in which Bill Clinton won a second term, while Republicans lost two seats in the House (offset by a gain of two in the Senate).

Many millions of Americans have much more at stake in 2016 than $11 a month. How will their interest sway the election?

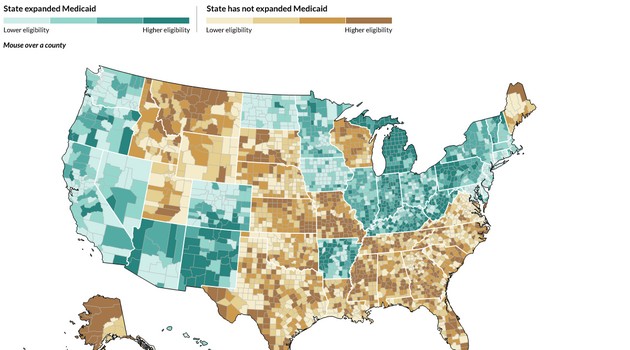

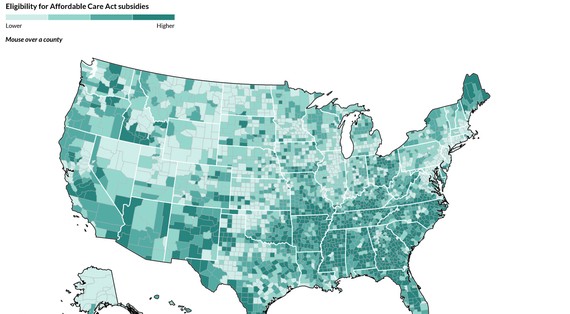

A couple of maps compiled by the Center for Equitable Growth offer some clues:

Medicaid Expansion Particularly Benefits Poor Regions of the United States

Not all states have taken part in the Medicaid expansion. The Supreme Court ruling upholding the constitutionality of the ACA also recognized the right of states to opt-out from the Medicaid component of the law, a right that 16 states have exercised, and another five continue to discuss. Most of the states that have expanded Medicaid would be expected to go blue in 2016 anyway. But not all: Ohio, for example, without which no GOP nominee has ever won the presidency; Indiana, for another, the reddest state in the Midwest; and Arkansas, Kentucky, Nevada, North Dakota, and West Virginia.

Affordable Care Act Subsidy Benefits Are Concentrated In The South

Unless the Supreme Court strikes down subsidies in the federal exchange in the pending case of King v. Burwell, ACA insurance subsidies are paid everywhere in the country. As the next map shows, eligibility for subsidy is concentrated in the red states. Not all of those eligible claim the subsidy. Many of those who do receive subsidies might be expected to vote Democratic in 2016 even if healthcare were not an issue. But some Republican-leaning voters will feel the hit—and especially in a tightly balanced state like Florida, that hit could have real consequences.

The early stages of a presidential contest are very much an elite sport, played by and for people who do not much worry about their insurance coverage. As the game broadens and widens, however, it will involve an ever-greater number of people for whom the risk of loss of health coverage will be an overwhelming consideration. It would seem an obviously urgency for Republicans to relieve as much of their anxiety as they can. Yet few Republicans perceive that urgency and even fewer are acting on it.

I’m going to put down a marker here. The next presidential election, like the last, will be decided by whether Democratic-leaning groups show up at the polls in large numbers—and maybe, at the margins, by whether the last few single percentage points of undecided voters choose “change” or “more of the same.” For those economically stressed toss-up voters—for the younger voters who sometimes show up and sometimes vote—the tipping point issue won’t be foreign policy. It won’t be ethics. It won’t be healthcare. It won’t even be the overall performance of the economy, which will be better, but still unwonderful. It will be that single haunting question, “Will I lose my insurance?”

If they don’t hear a clear and convincing “No,” they’re going to assume the answer is “Yes”—and most likely, vote accordingly.

David Frum is a staff writer at The Atlantic.