Where Iran Is Considered a Top Threat—and Where It Isn't

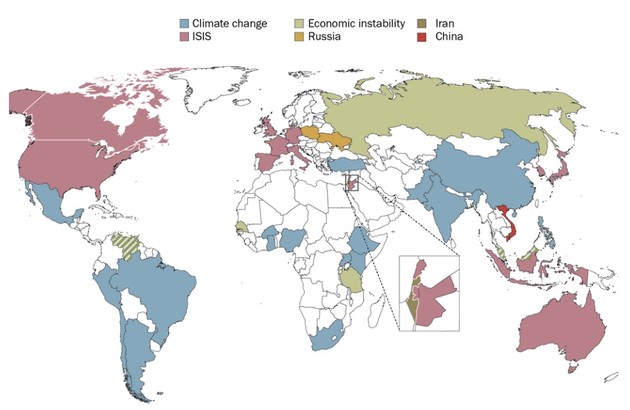

Mapping what concerns people most around the world

There’s only one country in which Iran’s nuclear program is considered the gravest threat in the world today. Not surprisingly, it’s the country whose prime minister just denounced the nuclear deal announced Tuesday between Iran and six world powers as a “a bad mistake of historic proportions.”

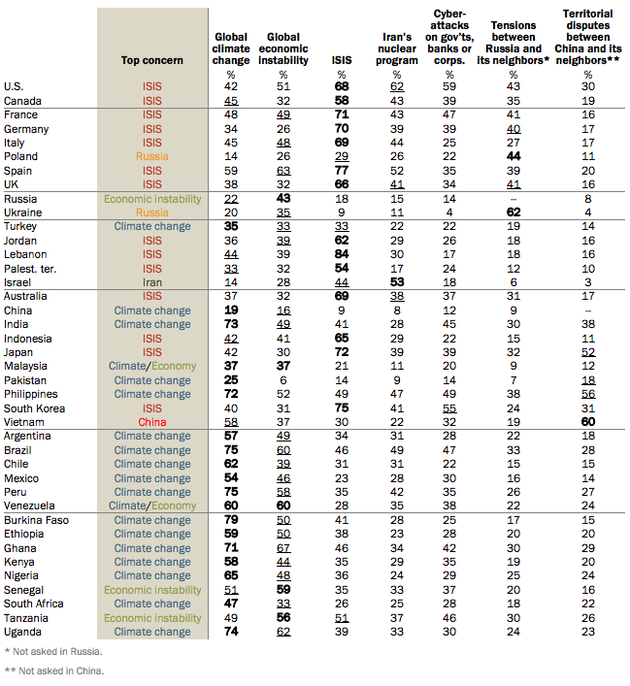

In Israel, according to a 40-nation Pew Research Center survey released on the same day as the nuclear accord, 53 percent of respondents said they were “very concerned” about the Iranian nuclear program, compared with 44 percent of Israelis who said the same about ISIS and 28 percent who chose global economic instability. When respondents were asked to identify their level of concern about seven global issues—from “not at all concerned” to “very concerned”—in no other country polled was Iran the greatest worry. Only in three of 40 countries did more than 50 percent of respondents cite Iran as a top concern: Israel, the United States, and Spain.

The Pew report doesn’t just chart the geography of alarm about Iran amid international efforts to restrict that country’s nuclear capabilities. It also reveals notable regional trends in what people consider threatening. Concern about climate change is most pronounced in Latin America, Africa, and Asia; fear of ISIS is most evident in North America, Western Europe, Australia, and the Islamic State’s neighbors in the Middle East. Economic instability is a secondary concern in many places, while cyberattacks tend to be downplayed as a danger throughout the world.

Percentage of Respondents “Very Concerned” About ...

The study comes with several caveats. Pew only surveyed 40 countries, leaving out not just most of Africa but also Persian Gulf countries like Saudi Arabia that consider Iran an adversary, and where public concern about the Iranian nuclear program may be more aligned with views in Israel. Rather than posing an open-ended question, the pollsters asked respondents to report their levels of concern only about the following international threats: global climate change; global economic instability; ISIS; Iran’s nuclear program; cyberattacks on governments, banks, or corporations; tensions between Russia and its neighbors; and territorial disputes between China and its neighbors. And it’s not as if concern about Iran is confined to just a few countries. In 22 of 40 countries surveyed, 30 percent or more of respondents said they were very worried about the Islamic Republic’s nuclear program.

But political leaders respond to public opinion, and the foreign policy they pursue is a product of prioritizing. Iran has been engaged in talks over its nuclear program with six world powers: China, France, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. In none of these six countries is the Iranian nuclear program the top geopolitical concern, according to the Pew report. In France, Germany, the U.K., and the U.S. (barely), ISIS is considered the gravest threat. In China, it’s climate change. In Russia, economic instability.

All this has implications for the fate of the Iran deal. As my colleague Peter Beinart has noted, there’s a chance economic pressure on Iran would decrease, rather than increase, if the U.S. Congress were to reject the current agreement and impose new Iran sanctions in an effort to extract additional concessions from its longtime adversary. That’s because European and Asian countries might respond to the U.S. move by withdrawing support for international sanctions against Tehran. Here’s what Beinart wrote in April:

[I]f the United States walks away from a deal that European and Asian governments support, those governments will not indefinitely maintain a sanctions regime that lacks domestic political support and costs them money. Last year, a report by the European Council on Foreign Relations warned that “those [in the United States] blocking implementation of a final deal … could endanger the international consensus backing sanctions against Iran.” If Congress torpedoes a deal, the report predicted, Europe might react “by easing its unilateral oil embargo against Iran.” In addition, “China and Russia … may become more sympathetic towards Iran’s position and see an opportunity to further advance their own interests at the expense of the US.”

China, in particular, has a history of strong economic ties to Iran, a massive thirst for oil, and little interest in doing America’s bidding in the Middle East. If the United States walks away from a deal that Beijing has endorsed, it’s only a matter of time until China imports large quantities of Iranian crude. Chinese impatience is already starting to show. Beijing imported 30 percent more oil from Iran in 2014 than it had in 2013. As the International Crisis Group’s Ali Vaez observes, “The high-water mark of international sanctions is already behind us.”

In the coming days, Israeli leaders will likely continue to condemn an agreement with an Iranian regime that they believe poses an existential threat to their country. But their criticism may find few echoes elsewhere in the world.