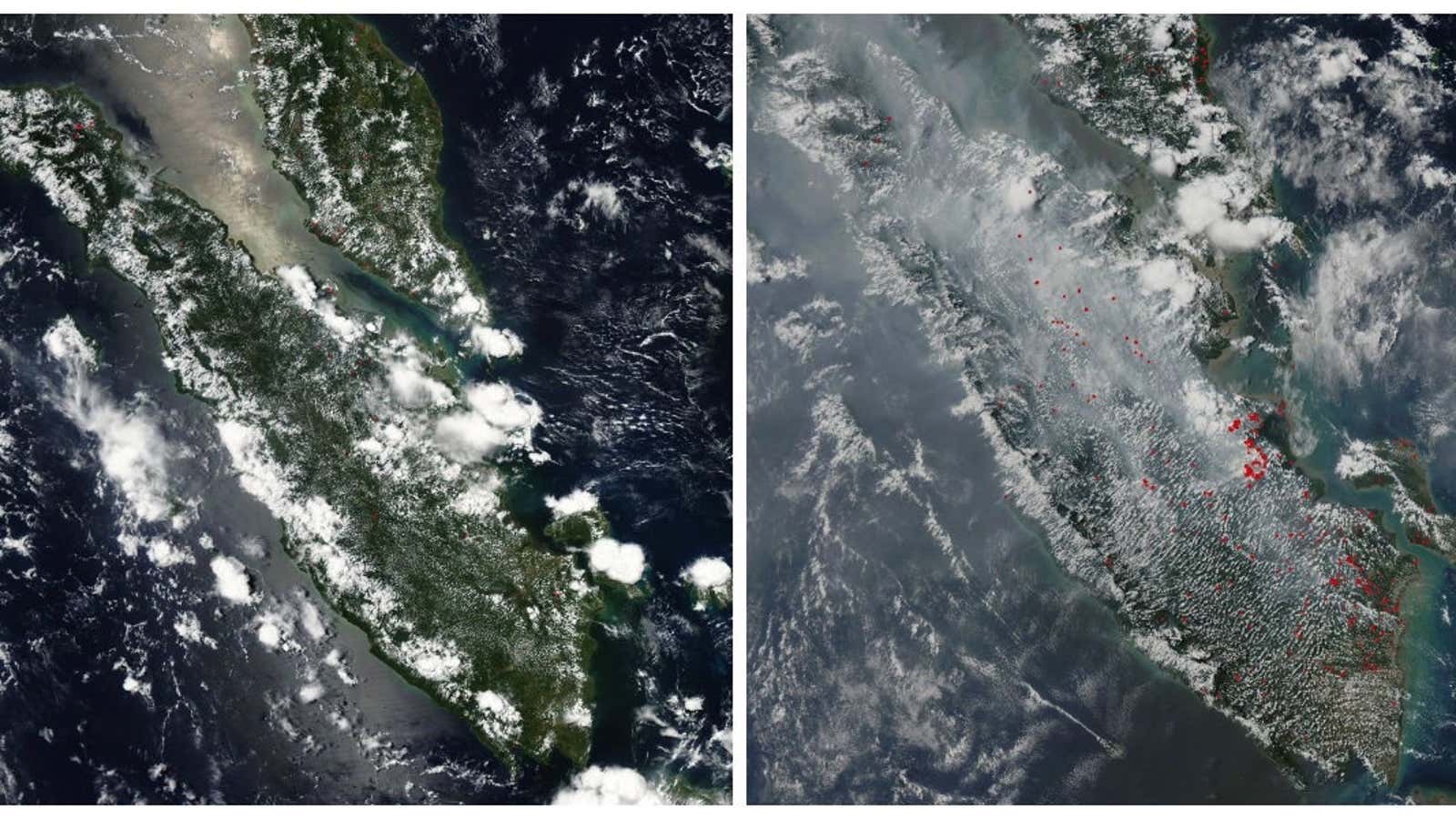

It’s dry season in Indonesia, which in some parts means it’s time to clear more land for palm oil plantations—with fire. In recent days, most of Sumatra (about double the size of Great Britain) was covered in a stifling layer of smoke so large it affected neighboring Singapore and parts of Malaysia, too. The smoke has also led to cancelled or delayed flights and health problems.

On the ground in Sumatran cities like Palembang, many turned to social media to vent their frustration. For instance a group of cartoonists—soon joined by others—used the hashtag #masihmelawanasap on Instagram and Twitter to share comments, street-level pics, and illustrations.

On Monday (Sept. 7) hundreds of students at Riau University staged a rally to express their demands to the government regarding the smoke. For starters, they said, authorities should declare an emergency since the situation affects public health. Those who set fires should be punished, they added, and hospitals should offer free medical services to those affected by the haze, particularly patients suffering from respiratory infections.

Recently, Norway’s $871-billion sovereign-wealth fund removed four Asian companies from its investment portfolio, citing the environmental damage they are causing by turning rain forests in Indonesia and Malaysia into palm oil plantations.

The problem is economics. Once land is planted with oil palms, it’s about double the value (link in Indonesian) of land that’s merely cleared by fire. And the latter is more valuable than uncleared land.

Palm oil is a widely used ingredient in processed foods and other items you find in your local grocery store. It pops up in soap, margarine, peanut butter, cookies, ice cream, lipstick, and toothpaste. It’s feedstock for biofuel, too. The world’s seemingly insatiable demand for palm oil creates economic conditions that favor the clearing of land ideal for growing oil palms.

That means every year in dry season, peat land and forests get scorched to make way for palm oil production.

On Sept. 5, Indonesian president Joko Widodo held a closed meeting in Jakarta with various ministers to try to find a long-term solution to the problem.

This post has been updated.