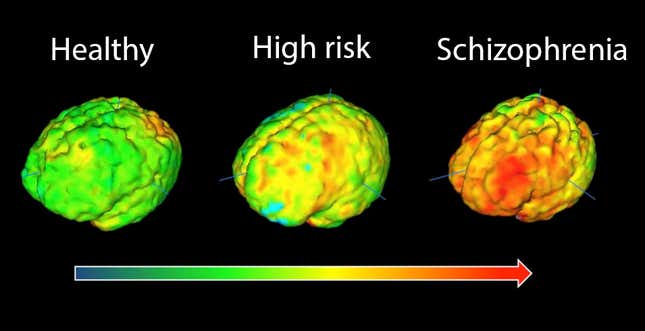

Schizophrenia is a serious psychotic brain disorder that can cause hallucinations, delusions, and paranoia. But a recent study, published Oct. 16 in the American Journal of Psychiatry, suggests that it may be possible to prevent the disease by calming the brain’s immune system.

Scientists have been exploring the link between schizophrenia and the immune system for the past 15 years. An inflamed immune system means there’s a heightened number defensive cells, called microglia, which prune weak synapses in the brain and neutralize bacterial infection. People with schizophrenia are known to have inflamed immune systems, but until now, scientists did not know if the inflammation preceded the disease.

The latest study, led by neuroscientist Peter Bloomfield at Imperial College London, found that people diagnosed as “ultra high risk” for developing a psychotic disorder (about 35% of these people go on to develop a psychotic disorder within two years) have hyperactive immune systems.

“Our findings are particularly exciting because it was previously unknown whether [microglia] become active before or after onset of the disease,” said Bloomfield in a statement. “Now we have shown this early involvement, mechanisms of the disease and new medications can hopefully be uncovered.”

Researchers injected a chemical dye into the brains of 56 people, including 14 with schizophrenia, 14 at risk of the disease, and 28 healthy people, then tracked microglia activity using positron emission tomography (PET scans). The study must be replicated with a larger sample size before the findings can be used to develop preventative schizophrenia treatments, and the full significance of high levels of microglia activity is not yet fully understood.

But Oliver Howes, who worked on the study and is head of the psychiatric imaging group at the UK Medical Research Council’s Clinical Sciences Centre, told the BBC that the study is “a real step forward.”

He said the microglia cells could be overacting and cutting the wrong connections in the brain. “You can see how that would lead to patients making unusual connections between what is happening around them or mistaking thoughts as voices outside their head and causing the symptoms we see in the illness,” he said.

Image by Gerry Shaw and EnCor Biotechnology Inc via Wikimedia, under CC BY-SA 3.0.