Beijing authorities banned an art exhibition about feminism and domestic violence just before it was set to open, organizers said on Thursday (Nov. 26).

The exhibition, timed for the United Nations International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, was due to open Nov. 25 at Beijing’s Gingko Space art gallery. More than 60 Chinese artists—half of them women—contributed work to the show. But when they arrived at the venue, they found themselves locked out and the gallery staff absent.

“The reason our exhibition was called off is pressure from higher authorities,” Cui Guangxia, the Beijing-based artist curating the event told the Guardian. Cui, who was detained for more than a month last year for his support for the pro-democracy Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong, said authorities think the event is sensitive because the focus is on domestic violence and gender equality.

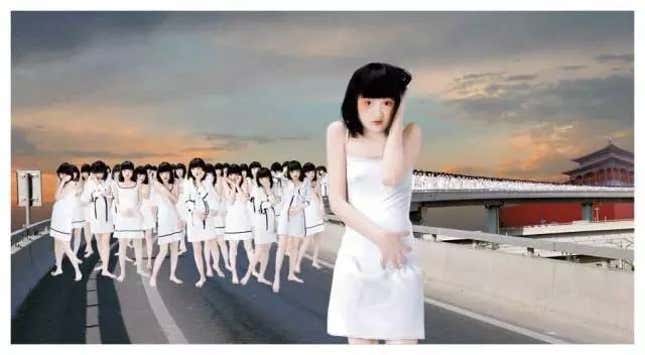

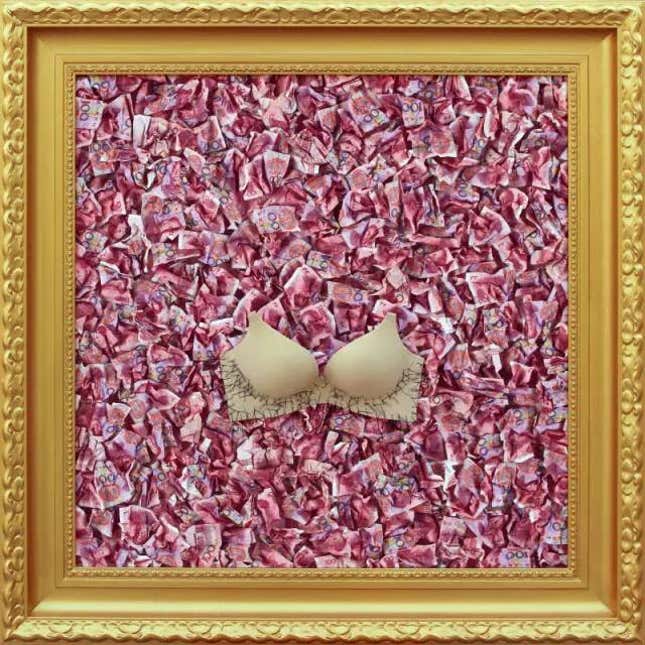

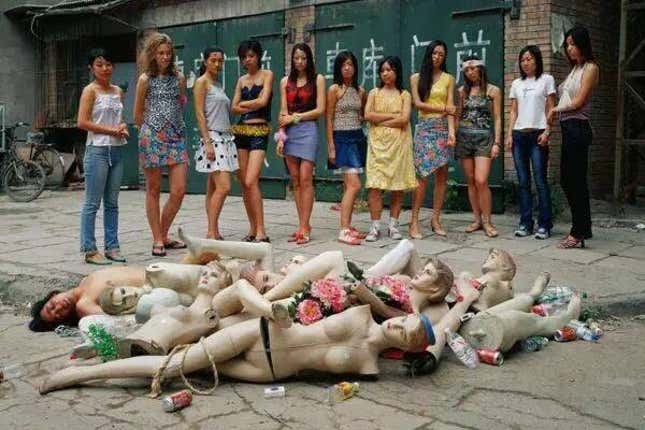

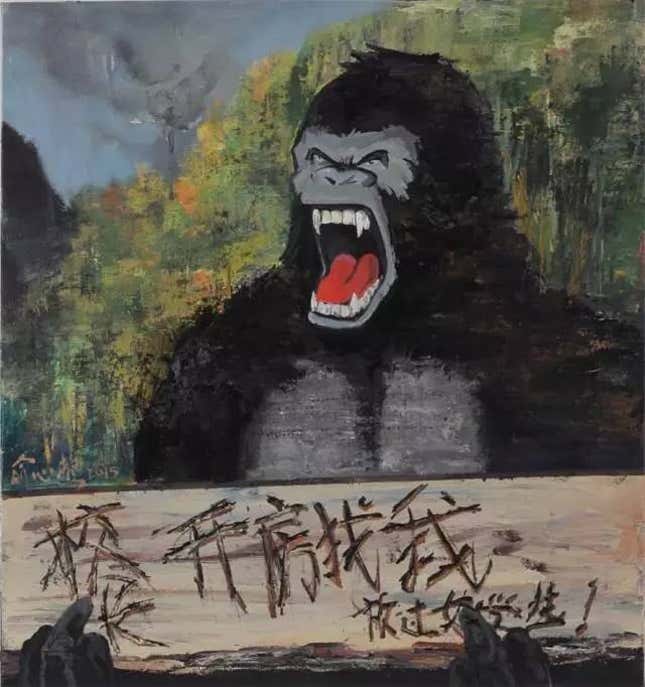

The artists’ works are unlikely to be publicly displayed in China any time in the near future. But photos of them are now spreading online in China, via several Wechat (a popular messaging app) accounts that were promoting the event. Here’s a selection of the art. (Most of the pieces are untitled online, but we’ve described them in the captions):

The exhibition is titled “Adultery: Cultural symbols of gender violence—HeForShe.” “HeForShe” is a solidarity campaign for gender equality initiated by UN Women. Adultery, one of the posts on Wechat explains, is written as 姦 in traditional Chinese, showing the deeply ingrained gender inequality in Chinese culture. 姦 is a combination of three 女, or female, characters. A gender symbol shouldn’t have become a symbol of infidelity, the post says (plus, 姦 also means evil and hypocrisy).

China’s government tightly monitors and controls feminist campaigns (as it does other citizen movements) that may spark public challenges or instability. Five feminist activists were arrested by police in March after planning to distribute leaflets and post stickers against sexual harassment. They were released more than a month later after they drew international attention.