In the early years after 9/11 the suicide belt, the car bomb and the homemade explosive device were the weapons of choice for jihadis: hidden, brutal and hard to counter.

But as 2015 heaves to a close, its atrocities littered across the calendar – Charlie Hebdo, Sousse, Garissa, Tunis, Copenhagen and Paris – it is the AK-47 that has come to the fore.

Across Europe more terrorist attacks have been carried out with Kalashnikov-type assault rifles this year than with any other device. In the 13 November Paris attacks, suicide bombers killed few but gunmen killed many. Further afield, in Tunisia and Kenya, it was also automatic weapons that did the damage.

The widespread availability of these guns has been known for years. But it took the scale of death meted out in Paris last month to force Europe to address the threat.

Now law enforcement officers across the continent are trying to establish some basic truths. Where do they come from? Who are the middlemen that deal in these deadly weapons? And why have they become so popular again?

The Balkan connection

Part of the answer can be found in a small cottage in the Balkan hinterland, beneath the mountains of central Montenegro. In one of two bare rooms, Zeljko Vucelic draws hard on a cigarette.

This is a poor place. Mould grows on the walls, damp seeps up from the floor, and the only possessions on show are an old TV, a cooker and a fridge.

The family has just about made ends meet for generations. But now Vucelic is facing the realisation that his brother, Vlatko, had been trying to make a little money on the side – as a bit-part player in the vast weapons trade.

“I haven’t been sleeping for nights. I’m trying to remember if there is anything to dig into, to grab and hold on to,” said Zeljko Vucelic.

On 5 November Vlatko Vucelic was stopped on a German motorway with a whole arsenal in the boot: a revolver, two handguns, two grenades, 200g of TNT. And eight Kalashnikovs.

Police have not linked Vlatko to any terror plot. But they do believe he was a cog, albeit a small one, in the illegal firearms trade, worth an estimated $320m (£210m) a year worldwide.

His journey, as detailed by the satnav, traced what experts believe is a well-worn route for weapons traffickers: Montenegro, through Croatia, Slovenia and on into Austria to a border crossing point into southern Germany near Rosenheim. The final destination was a car park in Paris.

Origins

When police use the word Kalashnikov to describe weapons they have seized, they are referring to a legendary brand that has had multiple reincarnations.

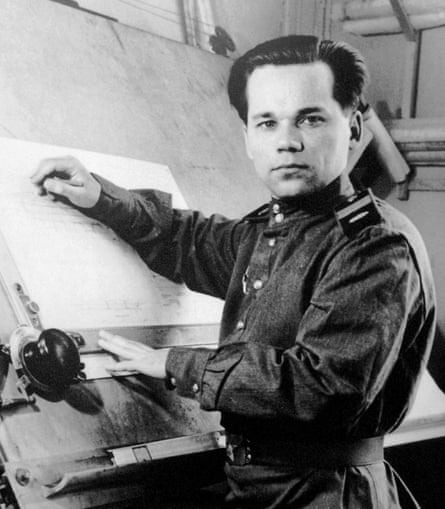

Designed by the Soviet general Mikhail Kalashnikov, the first model of the Kalashnikov gun, or AK-47, was introduced into active service in the Soviet army in 1948.

Today, however, the name applies to 200 types of AK-pattern assault rifles. According to Michael Hodges, author of AK47: The Story of the People’s Gun, there may be as many as 200m Kalashnikovs in the world, one for every 35 people.

They are manufactured – legitimately, for international trade – in more than 30 countries, with China leading the way.

But legal weapons can quickly become illicit contraband. China exports principally to African states. There, they can end up on the illicit market either because underpaid soldiers sell them on, or because states supply rebel forces in other countries.

Libya, with its own civil war to feed and a lawlessness unrivalled almost anywhere on the continent, has emerged as a huge funnel for the weapons.

A report by a UN panel of experts on the arms embargo on Libya has found that weapons have been illegally passed to 14 countries outside its borders, although no evidence of Libyan-sourced firearms in Europe has yet been acknowledged publicly. Most experts believe, however, it is only a matter of time before they are found within the European Union.

As well as the constant production of new AKs, at the rate of a million a year, there are tens of millions of Kalashnikovs in the western Balkans, the former Soviet Union and north Africa that are still working effectively, despite dating back to the 1980s and beyond.

In Albania alone, after unrest in 1997, about 750,000 Kalashnikovs disappeared, to become part of the black market in illicit firearms.

These older weapons, often rebuilt or reactivated by middlemen, are used by criminals and terrorists exploiting their extraordinary durability.

“It’s a very simple piece of kit,” said Mark Mastaglio, a UK-based ballistics expert. “It’s very easy to use, that’s why you see 12-year-olds carrying them. It is tough, it works in all kinds of environments – hot and sandy deserts, or in Siberia. Wherever it is stored it is resilient, and this is why it is so popular.”

In Serbia there are estimated to be up to 900,000 illicit firearms, mostly AK-type military weapons. In Bosnia there are an estimated 750,000 illegal weapons. Many simply went home with returning fighters as the protracted Balkan wars wound down in the late 1990s.

“At the end of the wars, whole battalions took their arms home,” said Aleksandar Radic, an arms expert. “For the first few years many hid them, just in case. But then people started to sell them on the black market, for as little as €100.”

Much of the heavy weaponry used in the Paris massacres appears to have come from Balkan sources.

Milojko Brzkovic, director of the Zastava arms factory in Serbia, said the serial numbers of eight rifles recovered by the French police suggested they were produced by his company. The M70 assault rifles – the Yugoslav version of the AK-47 – discovered in France were part of a batch sent to military depots in Slovenia, Bosnia and Macedonia by his firm.

But while discovering the origins of a weapon is helpful, it does little to help trace its path into the hands of an Islamist extremist.

“It is really difficult to trace the life cycle of a weapon,” said Ivan Zverzhanovski, based in Serbia, who works on a region-wide UN project to stop the uncontrolled proliferation and illicit trafficking of Kalashnikovs and other small arms.

“You might know the weapons were held in the Yugoslav army stock in the late 80s, but you don’t know where it was between the 80s and 2015. Therefore it’s really difficult to find out how they are really coming into Europe. Getting the right type of information is crucial.”

Routes

Vlatko Vucelic was allegedly part of what experts call the “ant trade” – small-scale smuggling of firearms into and across Europe. Until the point he was stopped, his life had been unremarkable. He is no Mr Big.

Unmarried with no children, he has no criminal record and, according to his brother, struggled to get by, earning less than €400 (£290) a month working in a vineyard in the summer.

A month and a half before his trip, however, Vlatko Vucelic, a man who had never travelled abroad and rarely drove a car further than a few miles from his home, applied for his first passport and an international driving licence.

“The guy who leaves his country for the first time, to take half the military barracks with him – how is that possible?” said Zeljko.

But it is a phenomenon that is entirely possible, as traffickers meet the demand for military-style weapons across Europe.

Zverzhanovski said: “The working assumption, which is probably correct, is that firearms come via the same routes that drugs do. A lot comes by road. It is micro traffic. There are no cases of large-scale smuggling – we are not seeing truckloads. It is two or three or five automatic pistols or disassembled assault rifles in cars or coaches.”

The volumes, compared with drug trafficking, are tiny – a handful of Kalashnikovs, as opposed to cocaine smuggled in multiples of tonnes – and the gangs behind the trade are also often tight-knit groups.

According to a report from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime: “The organised crime group responsible for the trafficking could be as small as one well-placed broker and his conspirators on the receiving end.”

While gun trafficking is not as lucrative as drug dealing, there are still huge profits to be made. Kalashnikovs can be bought in the Balkans for around €300 to €500, and sold in Europe for up to €4,500. But there is evidence, according to Nils Duquet of the Flemish Peace Institute, that prices are dropping, with an automatic rifle available for between €1,000 and €2,000.

Other attractions are the difficulties of detection, particularly across the Schengen borders, and the fact that in many European countries gun trafficking sanctions are less severe than drug smuggling penalties.

While the likes of Vlatko Vucelic are crucial to the trade, trafficking mules are not always required. In Denmark the main method of trafficking illicit firearms into the country is via heavy goods vehicles, primarily from the western Balkans, and in Sweden last year police intercepted a consignment of automatic weapons being transported in a box placed on a bus travelling from a town in Bosnia to Malmö. It was not accompanied by a passenger.

The middlemen

In the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo attacks in Paris, the Slovakian authorities quietly redrew their laws on deactivated firearms, making it illegal to sell them online, and forcing collectors who choose to buy a decommissioned Kalashnikov to register the firearm.

Their actions came amid growing evidence that several of the Kalashnikov-type firearms used by the Kouachi brothers in the Charlie Hebdo attacks in Paris, and by their friend Amedy Coulibaly, who killed five people in a kosher supermarket two days later, were bought legally in Slovakia as decommissioned collectors’ items.

The illegal conversion of decommissioned weapons, from starter pistols to Kalashnikovs, takes place all over Europe. In 2013 an EU report spelled out the threat: “Law enforcement authorities in the EU are concerned that firearms which have been deactivated are being illegally reactivated and sold for criminal purposes, [and that] items … are being converted into illegal lethal firearms.”

While decommissioning a Kalashnikov allows it to be legally bought by collectors, the mechanics of rendering the weapon inoperable differ across Europe.

In the UK, according to Mastaglio, there is a “gold standard” that means it is impossible for a firearm to be reactivated and used. But in some other countries, Slovakia included, it is the work of a couple of hours to make the weapon lethal again often by unblocking the barrel and re-installing the firing pin.

Investigations in France have focused on the trade in decommissioned weapons as a source for criminals, and now for terrorists. In 2013 the French arrested 45 people on suspicion of smuggling firearms from Slovakia and Bulgaria, in an investigation examining the “flow between arms collectors and criminal networks”.

Last year in Lille an investigation was opened into the middlemen who illegally reconverted decommissioned firearms. A Brussels-based engineer, a gun dealer in Belgium, and a Lille-based businessman, Claude Hermant, whose company deals in decommissioned firearms, have all been drawn into the inquiry.

Hermant has been held in custody since January, accused of the trafficking of decommissioned weapons. His lawyers say he has not been questioned in connection with the investigation into the attacks in Paris.

Brussels is thought to be another nexus for middlemen. With its history of lax firearms laws and a legal gun trade that has created a pool of talented firearms engineers, the unofficial European capital is at the centre of investigations into the sourcing of weaponry for terrorists.

Mehdi Nemmouche, accused of killing four people at the Jewish Museum in Brussels; Ayoub el-Khazzani, accused of attempting a mass shooting on the Thalys train in August; and Coulibaly are all believed to have found weapons from middlemen in Brussels. Belgian investigators also suspect that local dealers may have provided some of the weapons to the men whose assault on cafes, bars, a football match and a concert hall in Paris left 130 dead on 13 November.

There are regular arrests of Belgians who have illegally manufactured guns from scratch or, as is often the case, have reactivated supposedly “deactivated” weapons. One reason for Khazzani’s gun jamming on the Thalys train was that it was apparently made from different bits reassembled in Belgium.

The scruffy streets around the Gare du Midi in Brussels are said to be where much of the illegal gun trading takes place. “The transfer of firearms can happen anywhere: in someone’s apartment or a forest or a parking lot. It is certainly not limited to the area around the Gare du Midi,” said Nils Duquet. “This is a European problem. Wherever there is serious crime there will be a black market in guns.”

In the past two years, he said, terrorists had changed their modus operandi towards firearms rather than bombs.

“One reason is that the … explosives are harder to get and firearms are more easily available on the illegal market,” he said. “Automatic weapons are very suited to hurting a lot of people in a short time and that is what terrorists want to do. So there is growing demand, and there is also growing supply too.”

Demand

In the past four years the illicit firearms trade has been growing to supply demand from criminals who are increasingly using AK-47s in countries such as France, Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands.

A senior Croatian official said firearms had recently overtaken drugs as the contraband of choice. In 2010 the French authorities revealed seizures of firearms had soared by 79%, with 2,710 weapons recovered. At the same time, the French police began to notice that criminals were increasingly using Kalashnikovs.

“What was emerging was new,” Zverzhanovski said. “The French, especially, started picking up a major increase in criminal activity involving firearms, especially assault rifles, around 2011. They did a report on it; their language shows how surprised they were.”

Europol, the European Union’s police intelligence unit, said in 2011: “There is an upward trend [by organised criminal gangs] in the use of heavy small arms … such as assault rifles.”

The growing evidence of a problem led the French to tighten their gun laws in 2012, creating tougher sanctions for gun trafficking, with penalties raised to a €100,000 fine and seven years in jail.

But the availability and use of Kalashnikovs has continued, particularly in places such as Marseilles. In 2012 there were two shootings outside nightclubs on consecutive weekends in northern France by criminals armed with Kalashnikovs.

In March two people were killed and 10 injured when a criminal gang opened fire with Kalashnikovs in a pub in Gothenburg, Sweden. A Dutch police source said that since 2012 there had been 20 murders or attempted murders between criminal gangs who had used 44 types of firearms. Nearly half were Kalashnikov-type assault rifles.

Even in the UK, where the home secretary, Theresa May, boasts that tough border controls prevent the trafficking of powerful assault rifles into the country, police seized 22 Kalashnikov-style automatic assault rifles, nine Škorpion machine pistols, 58 magazines and 1,000 live rounds in a van leaving Cuxton marina in Kent in August, following the arrival of a boat from France.

For investigators trailing how jihadi terrorists manage to get hold of such weaponry, the nexus between organised criminals and terrorism is crucial.

The crossovers are evident in a string of Islamist-inspired terror atrocities from Mohamed Merah’s gun attacks in south-western France in 2012, to Nemmouche, to the January attacks in Paris by the Kouachi brothers and Coulibaly.

All were criminals who, having served prison sentences for their activities, emerged from their incarceration as newly radicalised jihadis with a mental address book of underworld contacts from their previous lives.

What is clear, according to Duquet, is that to obtain weapons it is not just money that is needed, but connections too. This is where often underestimated links between criminal gangs and European extremist networks can be important, he said.

The ability of these criminal extremists to access military hardware including Kalashnikovs has seen firearms rise to prominence as the weapon of choice for terrorists in Europe. According to the 2015 EU terrorism situation and trend report (pdf), firearms have become the most prevalent form of weaponry in terror attacks in the EU.

The state response

Inquiries into the slaughter in Paris are taking place against a backdrop of Europe rushing to close loopholes in legislation and fill in gaps in investigatory expertise that have existed for years.

When criminals used the weapons to mete out vengeance on each other the European authorities appeared leaden-footed. It was not until 2013 that Europol set up a unit of dedicated firearms experts. And according to a 2014 European commission report on gun trafficking in Europe, the last joint customs operation focusing on firearms was in 2006.

“It is really only relatively recently that firearms trafficking within Europe has become a priority,” said Nicolas Florquin, senior researcher at the Small Arms Survey. “Current knowledge on firearms smuggling in Europe remains patchy, gleaned from specific arrests and seizures, leading to wildly different estimates of the scale of the problem. It should not be so.”

In 2013 – as evidence of the grey trade in decommissioned assault rifles grew – discussions went on in the EU about the need to standardise methods to make the weapons inoperable. The changes, however, were deemed of “medium” priority.

But within four days of the Paris attacks last month, a directive to standardise the decommissioning of firearms to render them inoperable across the EU was hurriedly drawn up – a move the commission admitted had been “significantly accelerated” in light of recent events. It includes stricter rules to ban the private ownership of Kalashnikov-style assault rifles, even in deactivated form.

In Montenegro, the family of Vlatko Vucelic are much less mobile than the guns he was arrested with. They cannot afford to travel to Traunstein, where he is being held, to speak to him. The Montenegrin police have told them there is no evidence Vlatko’s trade was linked to the Paris attacks, but that is only of little comfort to them.

“How much could he have been paid for this?” asked his brother. “If it was a million, I could somehow get my head round it. But for sure it wasn’t that. We have struggled in our life for 50 years; we could have kept on going like this for the next 10 years, for the rest of our lives. If my brother is guilty of this, I would personally convict him to 30 years in jail.”

Additional reporting by Julian Borger, Ben Knight in Berlin, Fergus Ryan in Beijing and Chris Stephen in Tunis

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion