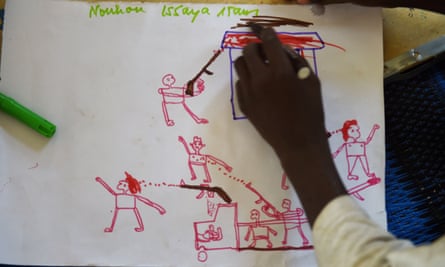

It’s been a year since members of the radical Islamist sect, Boko Haram, stormed the fishing town of Baga in northern Nigeria and killed an estimated 2,000 people.

It was the most brutal massacre yet perpetrated by the group and the once bustling Baga, home to 300,000 residents on the banks of Lake Chad, has since been become a ghost town.

“No one stayed back to count the bodies,” one resident told Human Rights Watch at the time. “We were all running to get out of town ahead of Boko Haram fighters.”

Today, the streets are empty. Fewer than 1,000 people remain, eking out a living from small farms hidden away from public view.

A resident of Maiduguri, the nearby state capital, said under condition of anonymity that Baga remains desolate under threat from Islamists.

“Even Mainok on the Maiduguri-Damaturu way, which is under Nigerian [army] control, is still a ghost town,” the source said.

“I don’t think Boko Haram is occupying any major town now but they are still scattered in the bushes laying ambush to travellers and attacking small villages.”

More than three million people have been internally displaced by the insurgency, but buoyed by new president Muhammadu Buhari’s promises, many had hoped they might have been able to return home by now.

In the run-up to the 2015 election, Buhari said ending the terror threat to the north-eastern states was his priority. Speaking soon after news of the Baga attack broke, he blasted his predecessor, Goodluck Jonathan, for his docile response, describing the incident as “an unspeakable massacre”.

“As a trained military man and administrator, come May 2015, the safety of each and every Nigerian life will be a priority,” he vowed. “This scourge, this season of death must be brought to a complete stop. I sincerely believe that Nigerians deserve better than this.”

But Buhari is yet to comment on the anniversary of the killings, and no commemoration ceremonies have been announced.

Administrators of a victims’ support fund set up after the attack have said they will soon start returning displaced people to the north-eastern states.

“2016 is the year of reconstruction,” said Alkasim Abdulkadir, spokesman for the fund. “The government of Nigeria remains committed to seeing that hundreds of thousands of displaced persons in the north-east move back to their respective communities.”

Lai Mohammed, minister for information and culture, even insisted in December the war against Boko Haram had been “largely won”, and that Buhari’s self-imposed deadline of December 2015 to wipe out the militants had been met.

Ambush

But local residents and news reports from the north-east tell a different story.

The media agency AFP reported that in July, a lorry carrying displaced people returning home to Baga for the first time since the massacre was ambushed, with eight people killed.

A few days later, Islamists were reported to have slit the throats of a number of fishermen and killed farmers who had returned to their farms, just in time for the harvest.

In September, a midnight attack on Baga and a neighbouring town, Monguno, left an unknown number of people dead after Eid festival celebrations.

Mark Amaza, a writer from Maiduguri, says the rest of Nigeria has become immunised to the horror.

“You get weary of bad news when it keeps recurring. These days, a tragedy isn’t so much one until someone you know is involved. So I was sad but I was numb [to the Baga massacre],” he says.

While displaced residents in the region wait to see if they will be rehoused, the war continues. “Our lack of institutional memory is why we don’t look back and correct our mistakes to avoid future occurrences,” Amaza says. “We never learn.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion