“People have had open marriages for ever … But they never end up working long-term.”

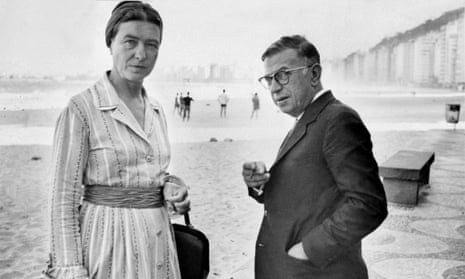

That statement by the biological anthropologist Helen Fisher must have been news to Simone de Beauvoir, the famously non-monogamous French feminist existentialist.

Fisher’s pronouncement, quoted in the New York Times recently, would also be questioned by the numerous celebrities said to have “arrangements”, and the half million or so of Fisher’s fellow Americans giving polyamory a try.

De Beauvoir considered her open relationship with Sartre the “one undoubted success in my life”. In terms of longevity, they had about half of us beat: their relationship, which allowed for affairs while they remained essential partners, lasted 51 years until Sartre’s death in 1980. Now, 30 years after De Beauvoir’s death, many of the criticisms of polyamory are rooted in the same stifling beliefs about female sexuality that she strove to dismantle in her day.

Take for example, the bias that “women only open up their relationships to please variety-seeking men”, which Anna North admitted was often assumed to be the case in an article on why we should be less “freaked out” by polyamory. In a piece for the New Yorker, Louis Menand argued that Sartre was a “womaniser” and De Beauvoir a “classic enabler”, going so far as to suggest that she feigned bisexuality to please him, and that parts of The Second Sex were written as a plea to him, reducing one of the 20th century’s greatest intellectual works to a marital squabble. De Beauvoir’s biographer, Deirdre Bair, argued that she was “subservient” to Sartre, and Hazel Rowley, in Tête-à-Tête, leaned heavily on scenes of De Beauvoir crying in cafes. But at the core of the assumption that non-monogamous women are doing what men want – not what they want – is a more pervasive assumption about female sexuality: it is men who have complex sexual needs, not women.

But as Libby Copeland argued, polyamory has woman-friendly roots: “Free love rejected the tyranny of conventional marriage, and particularly how it limited women’s lives to child-bearing, household drudgery, legal powerlessness, and, often enough, loveless sex.”

In an article on straight poly-relationships in Seattle, Jessica Bennett writes that, “the community has a decidedly feminist bent: women have been central to its creation, and ‘gender equality’ is a publicly recognised tenet of the practice”.

The actress Mo’Nique says that her open relationship was her idea. Simone de Beauvoir didn’t see herself as a tag-along polyamorist either. Attracted to both men and women, her open relationship meant that she didn’t have to choose between them. She felt the “urge to embrace all experience”, saw the ability to act on desire as essential to liberating oneself from male sovereignty, and was seeking to answer the question that we still grapple with today: “Is there any possible reconciliation between fidelity and freedom?” Polyamory, according to Copeland, was not just about sex, but about “remaking one’s own little corner of the world”, a terrifying prospect to those who want the world to remain the same, especially when it comes to established gender roles.

The most effective way to undermine someone’s empowerment is to pronounce their freedom an illusion. “If you could get her to talk about how she feels or how her husband really feels,” Fisher said of Mo’Nique, we might see a different story.

Open marriage has its challenges, as does monogamous marriage, as do all relationships. De Beauvoir did cry in cafes; she was sometimes miserable. Poly advocate Ken Haslam said that polyamory can be “polyagony”. Freedom can be overwhelming, which is perhaps why most of us don’t choose it in marriage.

It’s not a biographer, cultural critic, or biological anthropologist’s job to tell the story her subject wants her to tell. But in much polyamory criticism there is an unwillingness to allow for complicated female desires, a self-serving wish to shove narratives into neater packaging. As Dan Savage wrote: “Mo’Nique and [Sidney] Hicks’ marriage would only ‘seem’ rocky to those who regard monogamy, successfully executed, as the sole measure of stability, love, and commitment.”

It’s like looking at a Model-T and evaluating its worth as a painting. The Model-T isn’t a painting, was never trying to be one. Last month, Sarah Bakewell broke with other Beauvoir biographers in her book At the Existentialist Cafe, by portraying her as empowered in her open relationship, perhaps because she sought to understand “the arrangement” in the context of Beauvoir’s philosophy of freedom. When evaluating polyamorous relationships, the question should not be “is this what I, in my marriage, want?”, but rather, “did they achieve what they wanted?”

The story where the woman wants just one guy for ever is easier to tell – especially when men are the ones telling it. Menand ends his piece arguing that Beauvoir really just wanted “Sartre for herself alone”, citing rather unhelpfully, “every page she wrote”. Clearly it’s possible to read “every page [Beauvoir] wrote” many different ways, just as there are many ways to live and love.