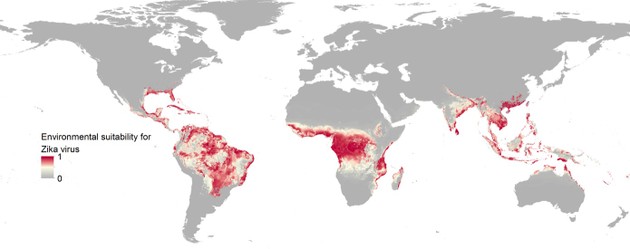

Where Zika Could Spread Next

Researchers estimate 2.17 billion people live in areas where the mosquito-borne virus could thrive.

More than 2 billion people live in parts of the world where researchers say environmental conditions are suitable for the spread of Zika, a mosquito-borne virus that is known to cause severe birth defects in babies born to infected mothers.

A team of researchers from the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, Sweden, Germany, and Brazil estimated in a new study this week that over 2.17 billion people on four continents live in areas at risk for transmission of the virus. Researchers say these locations have the ingredients necessary for Zika transmission: warm, humid weather, high population density, and the presence of Aedes mosquitoes, the insects that carry the virus.

Their map shows much of Latin America and virtually all of the Caribbean is at risk:

The risk varies in Brazil, the country hardest hit by the outbreak (the paper abbreviates the Zika virus as ZIKV):

Large portions of the Americas are suitable for transmission, with the largest areas of risk occurring in Brazil, followed by Colombia and Venezuela, all of which have reported high numbers of cases in the 2015-2016 outbreak. In Brazil, where the highest numbers of ZIKV are reported in the ongoing epidemic, the coastal cities in the south as well as large areas of the north are identified to have the highest environmental suitability of ZIKV. The central region of Brazil, on the other hand, has low population densities and smaller mosquito populations, which is reflected in the relatively low suitability for ZIKV transmission seen in the map.

Researchers said the southeastern United States, from Texas to Florida, is “highly suitable for transmission,” especially as temperatures rise in the summertime. Although no cases of Zika have been reported there, some sub-Saharan African nations, the northwest region of India, and the northernmost parts of Australia may also be susceptible to Zika spread.

U.S. health officials confirmed earlier this month that the Zika virus can cause microcephaly, a condition in which infants are born with smaller-than-normal heads and neurological defects. There is no treatment or vaccine for Zika infection, but scientists around the world have fast-tracked medical research since the outbreak emerged in Brazil last year. The World Health Organization in February designated the spread of the virus a public-health emergency of international concern, the most serious action the organization can take.