Recent extreme weather events—be it England’s blistering 2014 summer or California’s drought last year—can be traced to human-generated emissions. But how far back have our carbon-intensive ways caused similar events?

A team of researchers from Australia, Switzerland, and the UK have tried to answer that question. In a study published in Geophysical Research Letters, they analyzed extreme heat events over the past century.

Using computer models, the researchers dialed down different factors in the historical data, such as levels of carbon dioxide and other pollutants that were added to the atmosphere by the burning of fossil fuels. This provided a view of the world as it would have been without human activity, which the researchers compared with the real historical record.

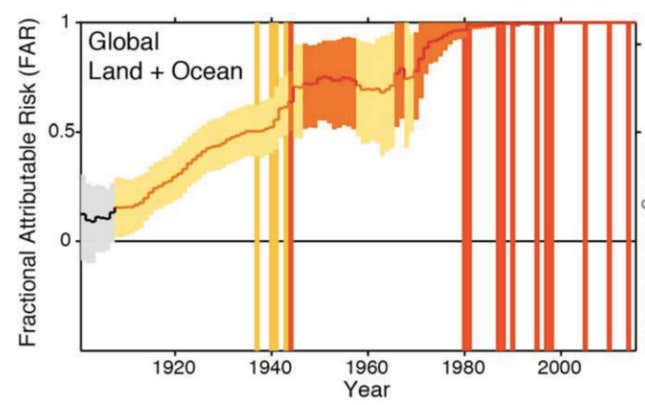

Since the beginning of the industrial era, carbon emissions and related pollutants have been added at increasing rates to our atmosphere. But it was thought that the real effects of these emissions only began in earnest after the 1960s, when a critical mass of pollutants had accumulated. However, the study found evidence of human impact on extreme heat events as far back as the 1930s.

“We restricted our search to extreme heat events, because we can reliably use the data going back in time,” says Erich Fischer of the University of Zurich, one of the authors on the study. Modeling humans’ impact on rainfall or droughts is much harder, he adds.

Fischer says the best way to understand how humans affect extreme weather events is to think about how smoking affects lung cancer. Not everyone who smokes will get lung cancer, but the chance of getting lung cancer is much higher among smokers.

“Without human-induced climate change recent hot summers and years would be very unlikely to have occurred,” the researchers concluded.