The internet affords us many powerful tools, but the ability to search for nearly any information one might desire has to be at the top of the list. Which is why it’s especially scary and sad that the online community of hate has beaten the search plowshare into a sword that can be swung with infinite range and rage.

As New York Magazine explains, by putting phrases or names into multiple parentheses (((like so))) anti-Semites mark people for attack, for others who share their vile outlook on the world. Whenever the search for (((this))) returns a result, as it did recently on New York Times reporter Jonathan Weisman, legions of bigots descend on the target, and make his or her life something like an online hell.

Weisman, in his story about being attacked, writes that, “An official at Twitter encouraged me to block the anti-Semites and report them to Twitter.” In other words, Twitter’s advice to users is that they police the hate themselves. It’s not an awful idea to ask users to report abuse, but the problem is that Twitter trolls can open up new accounts just as fast as Twitter closes down old ones. And with the power of search, newly opened accounts can quickly regain the followers and reach that shuttered ones had.

I haven’t signed up for Twitter or Facebook accounts for years, so I quickly opened up a browser in anonymous mode and went through the signup processes for each. Facebook stopped me several times, prompting me to use my real name. I had put in “Bad Guy” as my name, and eventually had to change it to “Badrick Guyowski” to get the service to let me in. Even when I was able to create an account, Facebook access was limited until I confirmed my email address–which was impossible for me to do, since I had entered a fake one. In essence, Mark Zuckerberg’s social network is inaccessible to someone who is not willing to part with at least some pieces of information that can be tied back to a real world identity.

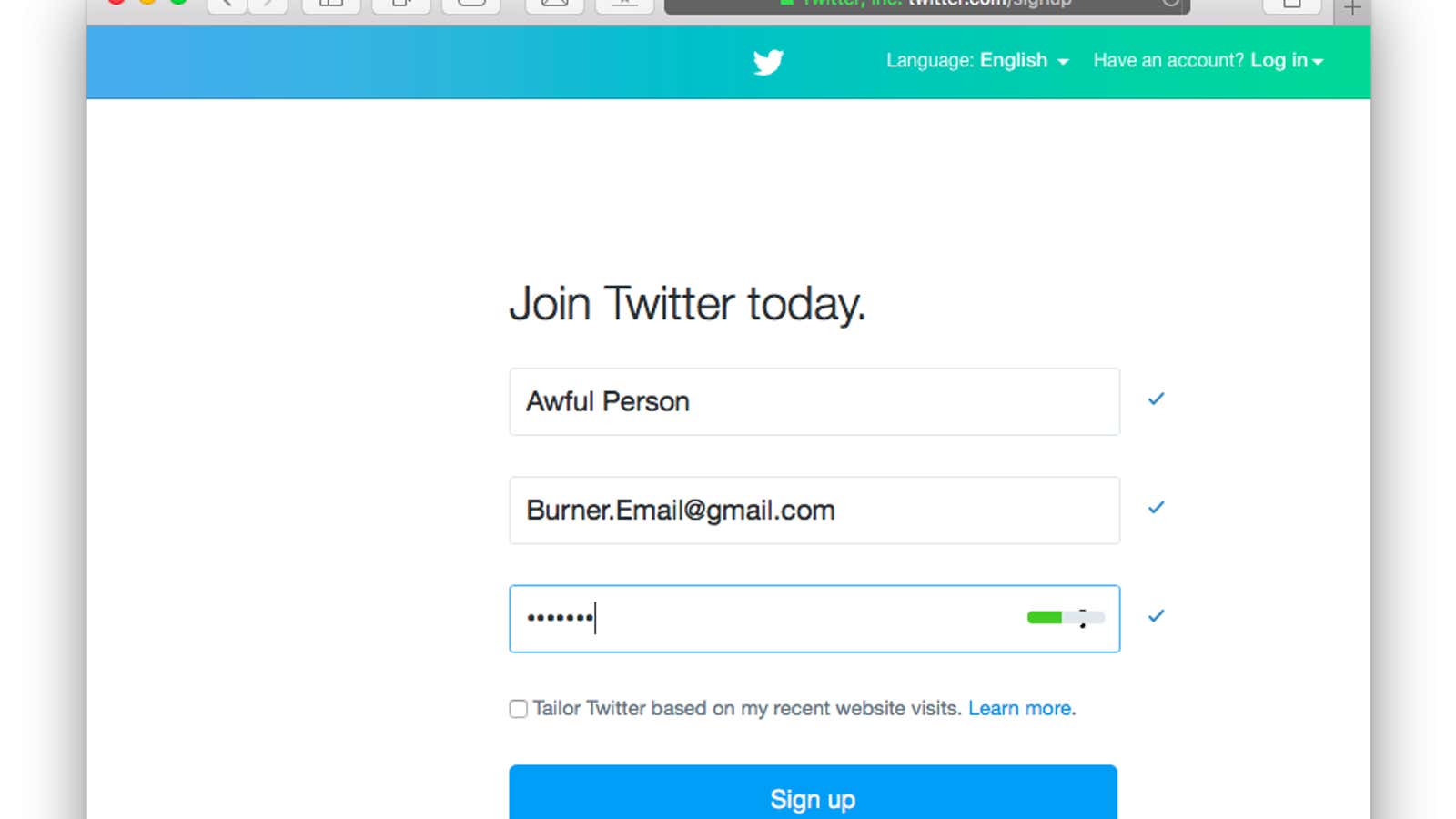

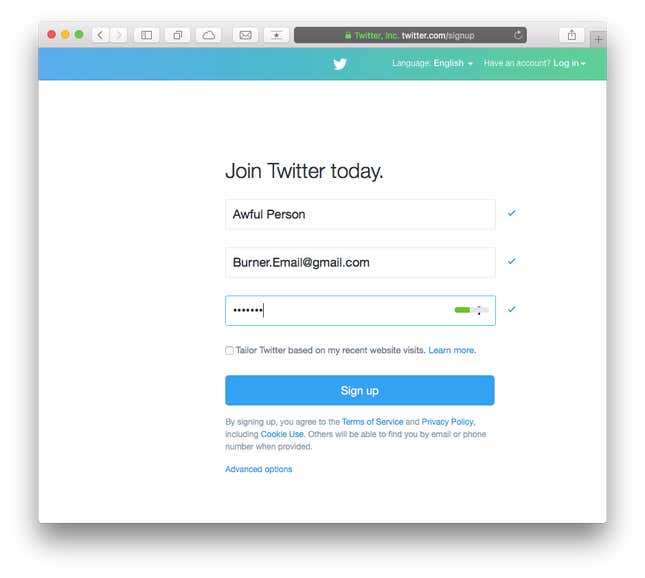

Meanwhile, Twitter accepted these credentials to allow me to create an account, without protest, and without a phone number:

Within seconds of creating the account, I was off to the racism races:

Years ago, Facebook made a policy decision that steered the company towards identity verification in order to cut down on duplicate, spam, and troll accounts. As the internet has become a larger and hairier place, this policy has not eliminated, but at least greatly reduced, the incidence of spam that most users see.

Meanwhile Twitter, perhaps desperate for growth, has left its signup process wide open to abuse. There essentially is no gatekeeper, which is why it is laden with trolls. Racism, sexism, misogyny, hate and anger of all stripes finds a home on its timeline. Many famous users, like Louis CK and Lena Dunham, have deleted their Twitter profiles, or at least the app, to limit their exposure to abuse.

Now, as recently-returned CEO Jack Dorsey pivots Twitter to being a community for worldwide discussions around live events, he also sees Twitter being overtaken in the number of Daily Active Users by visually-oriented services like Instagram and Snapchat. Some of the growing attraction to these networks surely lies in the secular shift from text to video that the entire internet is experiencing. But, both services require stricter identity verification than Twitter does, limiting the potential for trolling and abuse.

The conundrum Dorsey faces is that to crack down on Twitter abuse, he’d likely have to decimate his Daily Active User numbers, a key metric by which Twitter stock is evaluated on Wall Street. Analysts estimate that Twitter has less than 140 million DAUs. (Snapchat was just estimated to have 150 million DAUs.) Back in late 2014, Quartz reported that at least 23 million Twitter accounts were probably bots–not human at all. Since Twitter makes no distinction between bot accounts and human ones, requiring verification without making some kind of allowance for bots would wipe out millions of accounts that don’t have phone numbers or email addresses, since, well, they aren’t human. If Twitter’s DAUs crashed as a result, the company’s stock price could plummet.

But requiring verification would also wipe out thousands of accounts maintained by human purveyors of hate. These are twisted individuals who viciously attack public figures, comedians, actors, authors, journalists, feminists, politicians, teenagers, bloggers, people of color, LGBT people, people with disabilities–any person who is looked upon as other by those who police the world for people who do not conform to their narrow, unforgiving lens of appropriate human attributes and behavior.

A Twitter employee pointed out to me that the service has required phone number verification for abusive accounts since 2015. But again, it does not require a phone number for the creation of a new account–only after an account has already acted abusively. So, as readers of a Verge article about the verification requirement pointed out, the system allows abusive accounts to be created in the first place. And the phone number requirement is easily circumvented. Abusers can just create a new account. The power of searching for those (((parentheses)))) means that brand new accounts can quickly regain their lost followers, so there’s little at stake for abusers who get shut down.

Several years ago I praised Twitter for a clever and transparent solution to censorship that many governments around the world required the service to deploy. For countries with less than totally free speech, tweets that governments demanded to be censored would only be removed in those countries themselves–globally, the tweets would continue to exist. It was an elegant if imperfect solution to a hard problem.

Today, Twitter is in desperate need of a similarly elegant solution to its abuse problem. Jack Dorsey may have to take a hit to the company’s growth and its stock price, to fix things. But our real world and online identities have merged. And people don’t like to feel unsafe or subject to anonymous attack. If Twitter keeps shedding users who refuse to tolerate hate speech, Dorsey won’t have to worry about Twitter’s viability and future for too much longer, anyway.