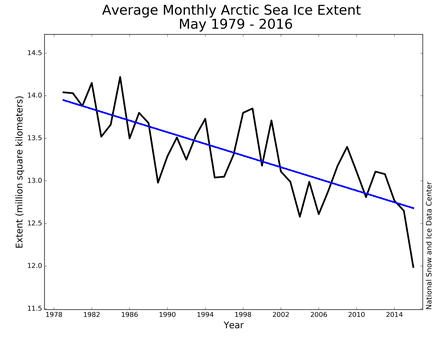

Arctic sea ice fell to its lowest ever May extent, prompting fears that this year could beat 2012 for the record of worst ever summer sea ice melt.

Data published by the US National Snow and Ice Data Centre (NSIDC) this week showed average sea ice extent for last month was more than 500,000 sq km (193,000 sq miles) smaller than May 2012.

The extent of sea ice in the Arctic is one of the key indicators of global warming, and the new findings have been greeted with concern by scientists. Although it is too early to say whether this summer’s ice extent will be the lowest recorded, if current projections follow the course of previous years then it will be at least one of the lowest ever.

Snow cover in the northern hemisphere was the lowest in 50 years in April, the NSIDC said, and Antarctic sea ice was below average for the time of year.

Warm air from Siberia and northern Europe were blamed for the decline in Arctic sea ice, which is consistent with predictions of climate change. The Arctic has warmed much faster than other regions, and the loss of sea ice is viewed as a measure of how much we are affecting the world’s climate.

Melting sea ice does not raise sea levels, because the ice is floating, but has a strong effect on the earth’s albedo – the reflectivity of the poles and other snow and ice covered areas. Ice and snow reflect some of the sun’s heat back into space, but when they retreat the dark areas remaining absorb more heat. This exacerbates existing warming effects, such as the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

In addition, melting sea ice in the Arctic is often a good indicator that land ice and snow – such as that which covers Greenland – is also melting, and land-based ice does contribute to sea level rises.

The NSIDC cautioned that current sea ice estimates were “tentative”, but added that they were “supported by other data sources”. The extent of sea ice will be closely watched this summer, as the lowest point of the year comes in September as the Arctic summer draws to a close.

Jonathan Bamber, professor of physical geography at Bristol University, told the Guardian: “We have already seen an unusually early start to melting around the margins of Greenland in 2016 and the new findings from NSIDC of exceptionally low sea ice extent for May and the lowest northern hemisphere snow cover for 50 years is in line with the longer term decadal trends for the Arctic as a whole. The region is undergoing warming at around twice the global average, and the ice is responding accordingly.”

Temperatures in the Arctic last winter were up to 10C above the average for 1981 to 2010, said Chris Rapley, professor of climate science at University College London. He also highlighted the reduction in thickness of the ice, which is another key indicator of climate change.

“The impacts on the Arctic ocean and land systems are transformational, creating huge problems for [people who live there] who on the basis of their traditional knowledge confirm that the climate system has already shifted well outside the bounds they have previously experienced. The situation is [also] changing the circulation patterns and behaviours of the atmosphere and oceans,” he said

The reduced extent of this summer’s ice is also a hangover from last winter, when sea ice was unusually slow to form because of higher temperatures in the surrounding oceans, according to Dr Finlo Cottier, senior lecturer in polar oceanography at the Scottish Association for Marine Science.

“This [slow formation of winter ice] leads to thinner ice that can break up more easily,” said Cottier. “The results also highlight the increasing significance of wind in deforming and breaking the sea ice cover.”

Sea ice extent in the last winter was at its smallest extent for winter since records began in 1979, data published in March showed.

Research by the campaigning group Greenpeace, published this week, suggests that melting ice in the Arctic may also alter weather patterns in the northern hemisphere, contributing to wetter summers in some areas and colder, stormy winters.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion