It’s impossible not to feel a little bit sorry for Cédric Rault-Verpre who lost it earlier this week after allegedly waiting four days for a ride, somewhere on the wild west coast of New Zealand’s South Island. Apparently the Frenchman could perfectly well have walked to his next destination in a day.

The road clearly wasn’t much used and it runs through the huge Paparoa national park , mostly beside the sea. That’s the west coast of New Zealand for you. Lots of people go there because they like it empty. But he couldn’t get a lift, and he ended up attacking the Welcome to Punakaiki sign in what must surely be an epically pointless piece of road rage.

But his inability to find a ride might mean something glummer than the seasonal effect of the antipodean winter on the volume of tourism. Maybe it means that even in friendly, chilled New Zealand, drivers no longer stop for hitchhikers. And if it does, well that really does sound like the end of the analogue version of the sharing economy.

After begging, hitching is the most elementary point of contact between those who have and those who have not. It is a basic exchange between need and ability to provide.

There is, it is true, an unstated contract in hitchhiking as there is in all forms of mutuality: the hiker will be at least polite and preferably entertaining. He or she will not, for example, exhibit intrusive personal habits, smoke, fart or sniff horribly (I admit that may only be a personal worry). The driver similarly will be prepared to sign up to the mutuality that offering a lift implies: safe, sober and going in the right direction.

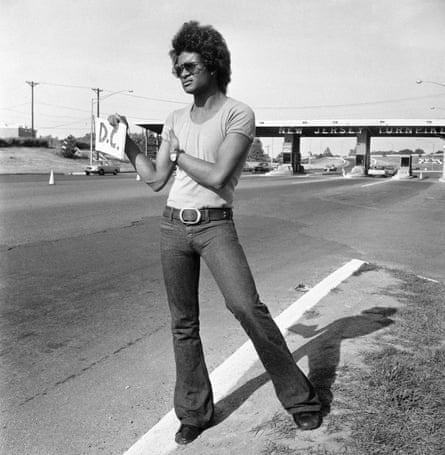

Yet even before the poor Frenchman had a tantrum on State Highway 6, there was plenty of evidence that hitchhiking is no longer a cheap and reliable way of getting to where you want to go. Maybe hitchhiking is just too analogue, a bit 20th century for millennials. In a hyper-connected age, when it’s necessary to text to announce a five-minute delay, there is diminishing appeal in committing a whole day (or even just an hour) entirely to chance.

Anyway, there are ride-sharing apps that mean you can be picked up at your door and taken to your destination, which offer some of the virtues of hitching but in an organised, digital kind of way. Yet they also mean sacrificing an element of serendipity, the happy accident of the unexpected place or person, to the security of predictability, and it feels like an expensive compromise.

Hitching depended on a sense of solidarity, and the sense of trust and mutuality that allowed me as a teenager, and practically everyone else I knew, to get around when there was no bus and no obliging parent. For me it was sometimes indispensable. Hitchhiking in uniform had me expelled from school (it was the uniform that did it).

People who hitched, and people who gave lifts to hitchers, were two sides of the coin of mutuality. People with assets regarded it as perfectly reasonable to share them. The dishonour was not in the asking but in the driving by. It was a kind of echo of the spirit that once unquestioningly sustained schools and hospitals, the idea which nowadays seems to be a fantasy, that we were there for each other.

Hitchhiking wasn’t all romance, obviously. Not being able to afford to get home, having to rely on the kindness of strangers, is seriously unromantic. Standing in the rain wondering if the car that’s just pulling up is driven by a kindly father figure or a serial rapist has an edginess that is not to everyone’s taste. Standing in the rain and no car pulling up is not even edgy.

Some people have always seen hitching as a kind of begging, either a kind of self-abasement or the exploitation of the generosity of hard-working folk. It’s hard to avoid the parallel with attitudes to benefits: the world is divided into those who see them as the essential connective tissue of society, and those who think there is no such thing as society.

Mistrust of motives is one of the most damaging solvents of the bonds that keep society together. Asking for and giving lifts is potentially dangerous. But probably not that dangerous. No one as far as I know has ever looked for the evidence, yet it seems likely that the number of people harmed in the course of asking for or giving lifts to strangers is only a tiny proportion of the number of such exchanges that have taken place. Yet somehow hitchhiking has more or less faded away, overwhelmed by prosperity and maybe a self-interest that has different roots to the self-interest of mutuality.

So, farewell hitching, and farewell that sense of trust and mutuality. But the spirit has not quite faded: it is still a pleasure to give a lift to a stranger heading in the same direction. It’s just that it’s so much harder to tell who they are, now that most people don’t like to ask.