The great women artists that history forgot

Rockoxhuis

RockoxhuisMuseums and galleries around the world are unearthing the work of great female artists who have been neglected or marginalised, writes Cath Pound.

“Why have there been no great women artists?” the feminist art historian Linda Nochlin famously asked in her landmark 1971 essay. The point was of course that there had been, but centuries of misogyny in the art world meant if you looked at museum collections and exhibition programmes you really wouldn’t know it. Things are still far from perfect but a number of recent exhibitions have been giving some truly great artists their long overdue public recognition.

Clara Peeters, whose beautifully rendered still lifes have beguiled visitors at the Rockox House in Antwerp is one such artist who is about to emerge from under the radar in quite spectacular fashion. When the show transfers to the Prado in Madrid in late October she will become, somewhat astonishingly, the first female artist to be given a solo show there.

Mauritshuis

MauritshuisA rare example of a successful female artist in the 17th Century, Peeters was an innovator in both form and content. At a time when women were denied access to formal training, and their subject matter was restricted, she used these limitations to push the boundaries of one of the few genres open to her. “She’s not allowed a big space so just decided to focus on a small one and does that really well,” says curator Alejandro Vergara.

Ignoring the high idealism of Rubens, which dominated the Antwerp art scene, Peeters chose instead to paint in the new realist style which was gradually gaining influence throughout Europe. “And if you’re painting in the realistic mode in Antwerp you’re really being very different to everyone else working there,” says Vergara. Whereas previous still life painting had been largely allegorical, Peeters’ work is characterised by a precise form and texture in which glowing vessels and foodstuffs contrast elegantly with dark unadorned backgrounds. Look at a painting by her and you are not reminded of mortality, you are reminded that you are hungry.

Prado

Prado“We do know that the leading collectors of the time had paintings by her,” says Vergara. But beyond that the details of her life remain a mystery. We can perhaps gain some clues to her personality from the numerous miniature self-portraits reflected in the gilt cups and goblets of her paintings. This was yet another innovation; no still life painter had previously thought to depict themselves in this way. Vergara sees it as a discreet but assertive proclamation of her worthiness, not only of being a painter, but also a woman painter. “How could you not read into that a certain will to be recognised?” Perhaps now, she will be.

Portrait of a lady

Unlike Peeters, the life of Louise Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun is well documented. She was the most successful, and expensive, portrait painter of the 18th Century, yet when the retrospective of her work opened at Paris’ Grand Palais in 2015, few outside academia had heard her name.

A precociously gifted artist known for her wit and beauty, Le Brun had established a portrait studio while still in her teens. At 23 she painted the first of many portraits of Marie Antoinette, whose direct intervention finally allowed her to enter the Académie Royale, from which she had previously been excluded due to her marriage to Charles Le Brun, an art dealer. Renowned for her exquisite treatment of colour, fabric and texture she could also, “capture a likeness like nobody,” says curator of the Paris exhibition, Joseph Baillio.

Wikipedia

WikipediaSuch success inevitably caused envy amongst her male peers. “It must have been galling to see that a woman got more money than they did,” says Baillio. When she exhibited her spectacular portrait of the Comte de Calonne at the 1785 salon there were rumours that it must have been painted by a man. Her royal connections forced her to flee France during the revolution and she spent the next 12 years painting the great and the good of Europe, including a six-year spell at the court of Catherine the Great in St Petersburg, before returning to France to live in extraordinary splendour until the age of 86.

Given her previous stature how is that we have not heard of her before now? Paul Lang, deputy director of the National Gallery of Canada where the exhibition is currently on show following phenomenally successful runs in Paris and at the Met in New York, identifies a number of reasons. “She was what we call in French, entre deux chaises, a victim of misogyny but also of feminism.” French feminists, particularly in the post-war years, despised her for using her beauty and portraying herself as a contented mother.

Wikipedia

WikipediaMuseum directors were also wary of putting on shows that consisted solely of portraits. Baillio recalls being told that the show wouldn’t draw crowds and that his catalogue would be remaindered. It has, in fact, been reprinted three times, and the popular response has been overwhelming. “Proof,” says Lang, “that if there is a great painter the time of rediscovery always comes.

Modern attitudes

O’Keeffe, Stettheimer, Torr, Zorach: Women Modernists of New York, currently showing at the Portland Museum of Art, examines the obstacles female artists faced in the early 20th Century in terms of production, interpretation and reception. It features three artists who are certainly worthy of rediscovery. The fourth, Georgia O’Keefe, needs no introduction, although she too was a victim of gender stereotyping, dogged by the sexual interpretation that her dealer husband Alfred Stieglitz insisted on imposing upon her work.

All four moved in the same avant-garde artistic circles which ostensibly supported women’s rights, but the gallery system gave fewer opportunities to women and traditional societal obligations still weighed heavily on their home lives. Margueritte Zorach, having spent time in Paris, was one of the first US artists to master Fauvist Expressionism, but when the demands of motherhood began to put a strain on her painting and she turned to batik and embroidery instead, her work was seen as less important.

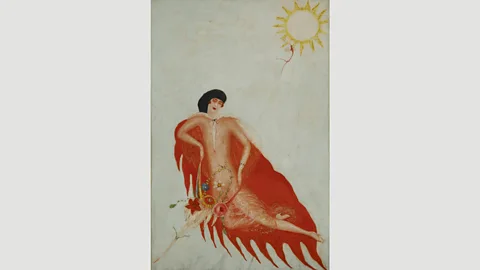

Columbia University

Columbia UniversityThe work of Florine Stettheimer, whose expressively attenuated forms and brilliant colours satirically explore her privileged world, was often dismissed for its delicate forms and personal subject matter. As a result she rarely exhibited and refused to sell.

The quality of work on display has been repeatedly remarked upon by critics, but it is that of Helen Torr, the least known of the four, which has drawn the most praise. Shifting between pure abstraction and the figurative, she shows a sophisticated feeling for tone, rhythm and colour. Tragically, during her life she was tormented by self doubt. Never much inclined to self promotion she was crushed by Stieglitz’s reluctance to display her work and was ultimately worn down by ill health and family obligations, putting the career of her husband before her own.

Smith College

Smith CollegeBut curator Ellen Roberts thinks that Stieglitz could have seen Torr as a threat to O’Keefe which is why he refused to exhibit her. “Steiglitz had promoted O’Keefe as the great woman modernist and there was no room for another.”

The bittersweet rediscovery of this lost great modernist is possibly the defining moment of the show, but she is in danger of sinking back into obscurity, for while both Stettheimer and Zorach have upcoming solo shows, there are no plans to exhibit Torr. We can only hope that Lang’s words will one day ring true for her too.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.