Bob Dylan by Andrew Motion

Dylan’s Nobel laureateship has proved controversial – which was presumably a part of the reason for awarding it to him in the first place. To shake things up a bit. But as a counterweight to those who think he shouldn’t have got the prize under any circumstances, and those who think the lyrics to the songs depend on their melody and delivery, which disqualify them from such an award, there are plenty of admirers, and plenty of ways to argue, that his words alone are certain good. The great protestations (“Blowin’ in the Wind”), the great love-murmurs (“Love Minus Zero”) and love-twists (“Tangled Up in Blue”), the great surrealist masterpieces of the Blonde on Blonde era (“Visions of Johanna”): all these contain the qualities we look for in poetry that matters. Concentration of language, formal expertise of one kind or another, and a clever balancing of articulacy and mystery. The same goes for his great ballads, which I love as much as any of these songs just named, and none more than his Baltimorean tragedy, “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll”. Here Dylan gives his account of the murder committed by William Zanzinger, of the criminally light sentence he received, and of “high office relations in the politics of Maryland”, in four headlong and largely unpunctuated verses. Everything about them is alert to the literary tradition in which they work, but everything stretches and extends that tradition, walking a fine line between lyric and narrative to catch the essence of both, and tumbling through rage into sorrow at its conclusion, without diminishing either: “Oh but you who philosophise disgrace and criticise all fears / Bury the rag deep in your face / For now’s the time for your tears.”

Andrew Motion’s latest collection is Peace Talks (Faber).

Cole Porter by Carol Ann Duffy

The earliest poems, as the Swedish Academy is trying to remind Bob, were sung, and this lyric DNA – from Sappho, Robert Burns and Christina Rossetti to Linton Kwesi Johnson – persists, both off and on the page. Kate Tempest’s work is at its electrifying best when she performs it. Other poets (Simon Armitage, Paul Muldoon) enjoy concealing the rock star’s leather jacket beneath the Oxbridge full-drag of the academic gown. (Of Armitage, the late Simon Powell, founder of Poetry Live, once affectionately remarked “he is a poet who knows his RS from his Elbow”.) One of the loveliest things I know is Christie Moore’s setting of Yeats’ “The Song of Wandering Aengus”.

I remember first hearing (in November 1967, aged nearly 12) the Beatles’ “I Am The Walrus”; how John Lennon’s lyrics, splicing Alice in Wonderland with a sexy surrealism, seemed to lead me, Pied Piper like, out of childhood. Thereafter, the albums I first bought as an adolescent were as much for the lyrics as for the music (teenage bedroom favourites committed fervently to memory: Leonard Cohen’s “Suzanne”; Joni Mitchell’s “Both Sides, Now”; David Bowie’s “Oh! You Pretty Things”; Simon and Garfunkel’s “Kathy’s Song”; Lou Reed’s “Perfect Day”). I think our most cherished song lyrics come from our youth, when they seem to be written especially for us, and in this sense poetry has the upper hand. Lacking a backing band, it necessarily has to do more with language. It also has a less fixed relationship with time. Cole Porter’s songs have delighted me my whole life, so I will choose his sublime “Ev’ry Time We Say Goodbye”:

Every time we say goodbye, I die a little.

Every time we say goodbye, I wonder why a little.

Why the gods above me, who must be in the know,

think so little of me they allow you to go.

And when you’re near, there’s such an air of spring about it.

I can hear a lark somewhere begin to sing about it.

There’s no love song finer but how strange the change

from major to minor,

every time we say goodbye.

But I’m also envious of and thrilled by just one line from Little Richard in 1955 – “A wop bop a loo bop a lop bam boom” – as, I am sure, Shakespeare would have been. Anyone who disagrees should leave the gig.

Carol Ann Duffy is poet laureate. Her latest books is The Map and the Clock (Faber).

Connie Converse by Emmy the Great

Connie Converse lived in Greenwich Village in the 1950s, where she wrote self-reflective, poetic songs that broke free of the folk tradition far ahead of their time. In 2004 some of her recordings were played on a radio programme, and her music was rediscovered, poignantly late. She’d been a missing person for 30 years.

When I listen to Connie Converse, I hear the internal world of a fiercely intelligent woman. With a knack for rhyming that foreshadowed Paul Simon, she used sparkling wordplay to throw light on roving women and misfits, and find beauty in the ordinary. On my favourite song, “Playboy of the Western World”, she sings, “When he walked through a room, it looked as handsome as Napoleon’s tomb / and the Ford he rode could have been Mercedes-Benz a la mode …”

Her story, marked by doomed ambition and the mystery of her disappearance, creates a satisfyingly tragic myth of an outsider artist, but her recordings, which were made by a friend at his kitchen table, are warm and alive. As her voice tumbles playfully over her melodies, pausing for funny, self-deprecating remarks, there is no room for the troubles of the future, only the fragile charm of Connie and her compositions.

To me, she’s a patron saint of singer-songwriters, a reminder to leave something of yourself in that moment, no matter who ends up listening.

Emmy the Great is touring the UK in November and December. Her album Second Love is out now.

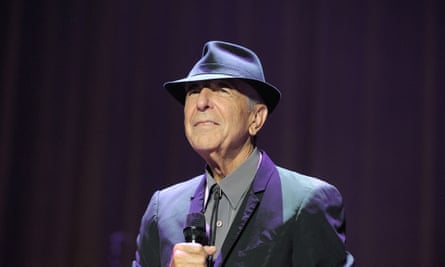

Leonard Cohen by Polly Samson

I don’t feel militant about Bob Dylan’s Nobel prize. I can argue it from either side: on behalf of pop music, which is an art form that doesn’t need to be validated with a prize for something it isn’t, or conversely as someone who writes lyrics and knows it sometimes doesn’t feel very different from writing words that are not intended to be sung.

That said, most great lyrics work because they are wedded to the right piece of music and the union of their parts is more potent as a song. Leonard Cohen rewards reading on the page and this is why to my mind, it is Cohen who lives alone above them all, Dylan included, on the uppermost floor of the Tower of Song.

Maybe this is because Cohen started out as a poet and words have always been his primary form of expression. He had published several collections, two novels, and garnered praise as well as at least one literary prize before he ever set his words to music. His lyrics exist like poems or short stories that cut to the core of human existence, and many of them have the same impact and interest when read divorced from their music. He can be brilliantly funny too: On ageing: “I ache in the places where I used to play.” On sexual jealousy: “And then I confess that I tortured the dress that you wore for the world to look through.” On the competition: “And all the lousy little poets coming round trying to sound like Charlie Manson.”

There isn’t another singer-songwriter whose lyrics I’d read before listening.

The Kindness by Polly Samson is published by Bloomsbury.

Nicki Minaj by Naomi Alderman

I taught a class on the lyrics of Nicki Minaj during a week of thinking about “experimental literature” at the Arvon creative writing centre in Devon. “We’re going to have to work on this,” I told them, “like you’d work on a page of Chaucer, going over it again and again until we understand it.” And the lyrics repay the work.

It’s easy to think that – bar a few notable exceptions such as Eimear McBride’s wonderful writing – the dense, allusive stream-of-consciousness style of Woolf and Joyce is these days just an experimental backwater of mainstream literature, loved by a few aficionados, ignored by the majority. But “difficult” writing, filled with cultural references and tricksy wordplay hasn’t vanished at all: it’s taken up residence in rap lyrics.

When I taught Nicki Minaj, we spent a long time looking at the lyrics of her verse in Kanye West’s song “Monster”. As the title suggests, it’s a piece about monstrosity, about knowing oneself to be an ego-monster but also realising that monstrosity is demanded by one’s audience. It features not only West but also Bon Iver, Rick Ross and Jay-Z. But Minaj’s verse blows them all out of the water.

Minaj namechecks familiar brands and characters: Willy Wonka, Tonka trucks, Bride of Chucky. They’re children’s toys, or childlike … but monstrous. Minaj is comparing herself to them: she might look like a toy, but she’s as sinister as Wonka, as deadly as a murderous doll, as powerful as a monster truck. And there’s a beautiful piece of wordplay in the line: “You could be the King but watch the Queen conquer.” Just swap the words King and Queen and say it out loud. I may be a woman, says Nicki Minaj in this verse, I may dress in pink, but underestimate me at your peril. “I’m a motherfucking monster.”

The Power by Naomi Alderman is published by Viking.

Lou Reed by Johnny Marr

“I’ll Be Your Mirror” by Velvet Underground is just one example of Lou Reed’s genius:

When you think the night has seen your mind

That inside you’re twisted and unkind

Let me stand to show that you are blind

Please put down your hands

cause I see you.

His reputation for documenting the more subversive side of human nature is well known, but it doesn’t tell the whole story of a writer who had real insight into human frailty and vulnerability – cruelty too; “Caroline says, as she gets up off the floor, Why is it that you beat me?, it isn’t any fun.” He turned slang into poetry, very deliberately using modern language to tell his stories of the city, and he made street talk into literature. His titles alone make him as good as anybody; “Satellite of Love”, “Venus in Furs”, “White Light / White Heat” almost define the rock era, and that the young man who first became known for writing a song called “I’m Waiting for the Man” at the age of 23 could turn his talent to write “Perfect Day”, a song which would surely be a contender for “song most universally loved”, says it all.

Set the Boy Free by Johnny Marr is published on 3 November by Century.

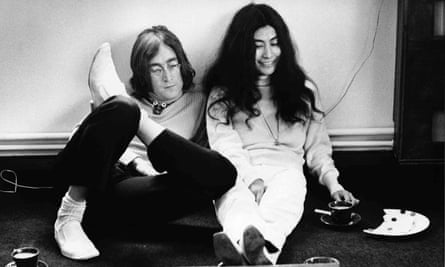

John Lennon by Amit Chaudhuri

Unlike Paul McCartney, after the breakup of the Beatles, Lennon never returned to the remarkable and noticeably unusual songs he’d written when he was in the band. McCartney sang “Yesterday”, “Hey Jude”, and other Beatles numbers in his concerts, putting his seal of ownership on them; Lennon only occasionally emerged from semi-retirement, and it’s no longer clear what he thought of “Norwegian Wood”, “Being for the Benefit of Mr Kite”, “In My Life”, “Revolution No 9”, or “Across the Universe”. Like Rimbaud, it was as if he’d sloughed off his former self like a skin while crossing a border.

Yet Lennon’s musical and conceptual intelligence, and his approach to the pop record, were fundamental to the Beatles’ evolution: there is no challenge presented, post-Beatles, by the recordings of its other members. Only Lennon continued to shock, delight, move and surprise. There’s the first album, John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band, which was made as if it were meant to have no listener but Lennon, counsellor to his own pain, assessor of his own worldview: “God is a concept by which we measure our pain / I’ll say it again … / I don’t believe in magic / I don’t believe in I-Ching / I don’t believe in Bible … / I don’t believe in Gita … / I don’t believe in Elvis / I don’t believe in Zimmerman / I don’t believe in Beatles / I just believe in me, Yoko and me, and that’s reality.” In this album, Lennon turned the flu-afflicted scream he’d unleashed long ago in “Twist and Shout” into a hurt, spiritual roar, a hurt he also expressed in the most tender melodies, in “Love” and “Hold On”, and in the tranquil, scathing detachment of “Working Class Hero”. Lennon’s greatest achievement in the artistic domain was his ability to say “no”; this, rather than ideology, was what made him political, as well as philosophically unique. This unforgiving but liberating quality of refusal is there in the second album, Imagine, and though the title song became a bestseller, its message, if you ignore the comforting hook, sweetly advocates the same radical loneliness that “God” had earlier: “Imagine there’s no heaven / It’s easy if you try / No hell below us / Above us only sky’. Very different from Zimmerman.

Odysseus Abroad by Amit Chaudhuri is published by Oneworld.

Joni Mitchell by Kathryn Williams

What do Joni Mitchell’s songs mean to me? Well, she says it best on the title track of Blue – they are permanently under my skin: “Songs are like tattoos, you know I’ve been to sea before … crown and anchor me, or let me sail away.”

The first Joni Mitchell record I bought was her first album, on vinyl. I grew into her way of speaking in song, started to learn her phrasing and began to collect more of her albums. It was like collecting glass marbles. The spherical shape was the same, but with a different coloured flame inside, twisted in a different spiral.

Joni can be conversational, poetic, philosophical, barbed – and make all that happen in one line: “Just before our love got lost you said / ‘I am as constant as a northern star’ / and I said, ‘Constantly in the darkness, where’s that at? / If you want me, I’ll be in the bar … ’” The shapes of the words and how they move alongside each other are perfectly formed, perfect to sing. “The Last Time I Saw Richard” is the prophetic song for all of us romantics to fear. It unfolds like a Raymond Carver poem. Showing not telling, and utterly heartbreaking.

As a songwriter, a female one at that, people comment on my singing voice far more than my lyrics. It’s as though they think we are not responsible for the words, just our voice. And I think that Joni Mitchell is often overlooked as the amazing lyricist she is. But she is a painter and her lyrics are a full sensory event. Pictures form in my head, I feel her pain, and I am taken to the places she sings about. I see her as a patron saint. She makes writing lyrics seem effortless … but there is only one Joni Mitchell.

Resonator by Kathryn Williams is released on 11 November.

Paul McCartney by Blake Morrison

Not many songwriters appear in poetry anthologies. Cole Porter, Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen are among those who have, or who deserve to, but the odds are always against it, both for good reasons (without voice, melody, orchestration and arrangement, few lyrics work on the page) and for bad (literary snobbery on the one hand, and the exorbitant cost of permission fees on the other). Karl Miller was sticking his neck out when he included “Eleanor Rigby” (and Pink Floyd’s “Arnold Layne”) in his Penguin anthology Writing in England Today (1968), along with Philip Larkin, Seamus Heaney and Thom Gunn. But he was right to recognise its poetic resonance – from the surreal image of Eleanor Rigby “wearing the face that she keeps in the jar by the door” to the detail of Father McKenzie “wiping the dirt from his hands as he walks from the grave”, it’s a plangent evocation of modern day loneliness.

McCartney is sometimes dismissed as sentimental (the schmaltzy foil to the bad-boy cool of Lennon) but “Eleanor Rigby” is as bleak as anything by Samuel Beckett: no one listens to Father McKenzie’s sermon, no one comes to Eleanor Rigby’s funeral, “no one was saved”. It’s a reminder of the range of tones McCartney is – or was – capable of: in this case melancholy (“all the lonely people”) but elsewhere parody (“Back in the USSR”), comedy (“Lovely Rita”), satire (“Paperback Writer”), nostalgia (“Penny Lane”) and raucous boogie-woogie (“Lady Madonna”). He can do sad as well as happy, moody monologue as well as sing-along. And at best the words escape whatever it was that set him off, leaving room for us to inhabit them: I’ve been listening to “Fixing a Hole” since its release and I’m still working out what it means.

Shingle Street by Blake Morrison is published by Chatto & Windus.

Mary Margaret O’Hara by Lavinia Greenlaw

When I was 19 and newly in the grip of writing, I joined a band. Asked to produce lyrics, I intensified my poems. Perhaps I thought that they could be freeze-dried and then rehydrated with a tune. The results were ungainly. Good singer-songwriters must have an extra layer of judgment that enables them to see what most of us need to be shown. Mary Margaret O’Hara is best known for Miss America (1988), and has released just one album since.

She builds songs out of spare phrases that light each other as the parts of a poem should. She sings this way too, as if making a series of gestures which have taken their time to become clear. You get the impression of distillation and deep thought in the making of songs that resist their own weight: “You just want to push somebody / And a body won’t let you. Just want to move somebody / And a body won’t let you.” O’Hara resists stabilisation, something I understood when I saw her perform live. She has a decisive but off-kilter way of moving – a lurch, a flick of the hand, a foot stamp that are impossible to relate to what you’re hearing. It’s as if she has a sense of detail so latent that no one else can detect it. Her lyrics are published in brief lines full of quiet swerves: “So sorry if I can’t stop pretending / So sorry if I don’t let you go / Like this but not like this is ending / I think you know. / I think you know. / Help me lift you up.” They can be heartbreaking in their generosity.

A Double Sorrow: Troilus and Criseyde by Lavinia Greenlaw is published by Faber.

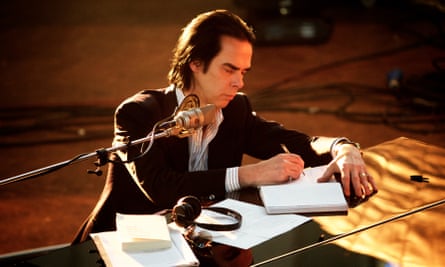

Nick Cave by Ian Rankin

“Hands up who wants to die?!!” Those were the first frantic words I heard Nick Cave sing. They’re from the opening track of a 1983 four-track EP by the Birthday Party, a thing of Grand Guignol excess culminating in a four-minute horror film (“Deep in the Woods”). From the beginning, Cave was an artist who immersed the listener in revelatory imagery and creeping doom. The Old Testament, delta blues, and Sergio Leone westerns infused his song writing. He could be urgent and kinetic, or mellow and thoughtful. “The Ship Song” could have been penned by Leonard Cohen, but it’s hard to imagine anyone other than Cave creating darkly compelling narratives such as “Red Right Hand” and “Jubilee Street”, while his album Murder Ballads has a body count that would shame Tarantino. Cave’s new album, Skeleton Tree, is a starkly intense listen, foregrounded by personal tragedy. That he makes art from his loss is testament to his sense of duty to the songwriter’s craft, and the title track (which closes the album) is full of quiet yearning, along with acceptance and resolution. The album as a whole reminds me a little of Dylan’s masterpiece “Blood on the Tracks”. Cave himself may not be getting the Nobel any time soon, but right now he is one of our very best lyricists and storytellers. It will be fascinating to see what he does next.

Rather Be the Devil by Ian Rankin is published by Orion.

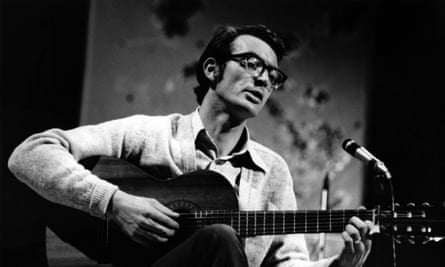

Jake Thackray by Roger McGough

I have always had a soft spot for the artists who came out of the northern music hall, folk club tradition, singer-songwriters like Stan Kelly, Mike Harding and Victoria Wood, and above all, Jake Thackray. Born in the West Riding in 1938 and educated by Jesuits in Leeds, he graduated from Durham University before leaving the country to teach in France for a number of years. And so, while we were dancing down at the Cavern, he was falling under the influence of Georges Brassens and Jacques Brel. He left as a gruff Yorkshire lad and came back a smooth, silver-tongued chansonnier.

His deep, rich baritone voice, intricate jazz-flavoured guitar playing and saucy yet timeless and sentimental lyrics made him enormously popular on the folk club circuit, and although he found nationwide fame following regular appearances on TV programmes such as The David Frost Show and Esther Rantzen’s That’s Life, he found little pleasure in performing in large theatres. Staunchly Catholic and leftwing, he could never understand why people would spend their hard-earned wages listening to him.

A craftsman of form, language and melody, he wrote of jilted lovers turning to drink, of grotesque relatives, lusty blacksmiths and gabby ladies, but with more compassion than venom. His was a gentle humane satire. At the jumble sale, “Where ladies of the village fight like visigoths for pillage” he found love and assonance among the bric-a-brac: “Romance perchance prevails at humdrum jumble sales”. Sadly, and puzzlingly to his many fans, he disappeared from public view, and died in Monmouth aged 63. Had he been born in France where the poet/singer tradition is long-established and where there is little distinction between “serious” and “popular” music, Thackray would surely be recognised as the major artist many believe him to be.

The Likes of Us, featuring Roger McGough and LiTTLe MACHiNe, is out now.

Tamara Lindeman by Richard Williams

Bob Dylan aside, the singer-songwriter I’ve listened to most over the past year, and to whom I expect to be paying attention for many more to come, is Tamara Lindeman, a 31-year-old former actor from Toronto who, under the name the Weather Station, performs songs notable for a conversational fluency, a diarist’s powers of observation and a quiet refusal of emotional simplicities. “I see everything from multiple perspectives,” she has said. “That’s sort of been a weakness in life but also a strength. I’m really interested to write a song where I can encompass all the different truths about a situation or all the different ways in which I see something, because it feels like that’s the way things really are.” The Weather Station’s third album, Loyalty, significantly expanded her audience last year through songs that captured moments in life with a subtle acuity, set to flowing melodies. One of them begins: “You looked so small in your coat, one hand up on the window, so long now you’d been lost in thought.” Another: “I don’t expect your love to be like mine. I trust you to know your own mind. As I know mine.” Reading her verses, with their finely wrought understatement, punctuated like prose but weighted like poetry, it’s hard to imagine them being turned into songs; hearing them sung, it’s impossible to imagine them being anything else. Comparisons with any other folk-rooted Canadian singer-songwriters, female or male, are facile and misleading: this one, too, has her own voice.

The Blue Moment: Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue and the Remaking of Modern Music by Richard Williams is published by Faber.

Steve Kilbey by Michel Faber

Dylan’s Nobel win was long overdue given the influence his songs have had on culture worldwide, but to be honest lyrics don’t mean much to me: I go for the music every time. And on Dylan’s records, the music is just there to provide a non-intrusive backdrop for the words, which is exactly the opposite of what I prefer. I want voices to function as instruments, abstract as an oboe or a squall of feedback.

That’s not to say I’m immune to good words. Leonard Cohen is a fine poet (although I’m mainly attracted by that sepulchral croon haloed by his female backing vocalists), Joni Mitchell is good too (although I mainly admire her as a bandleader), Loudon Wainwright, Peter Gabriel, Kevin Coyne … they all touch me. The other day I read the lyric booklet of Chris Cutler’s Domestic Stories and was struck by how strong the poems were. Then I played the CD and the meaning of the words evaporated in a puff of sound.

The only wordsmiths who seem to be able to get through to me are Steve Kilbey of the Church and John Balance of Coil. Kilbey’s lyrics are suffused with loss and addiction, lightened by wry humour. I’ve loved them for 30 years, despite never having taken an illegal drug. Likewise Balance’s voice – increasingly haunted by childhood traumas and the alcoholism that would kill him – resounds in my head, clear as the saddest bell in the world. “Wise words from the departing / Eat your greens / Especially broccoli / Wear sensible shoes / And remember to say ‘thank you’ / Especially for the things / You never had.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion