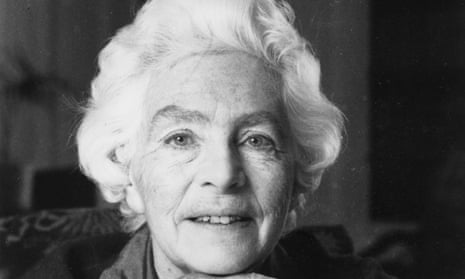

In the introduction to her new book, Sounds and Sweet Airs: The Forgotten Women of Classical Music, Anna Beer informs us that she will not present us with “a catalogue of injustice and despair”. It would have been “all too easy,” she writes, “to represent every female composer’s life as a futile struggle against impossible odds.” Rather, she wants to “celebrate the achievements” of eight women who, despite considerable practical and ideological restraints, did compose music for public consumption, starting with Francesca Caccini at the start of the 17th century and ending with Elizabeth Maconchy who died in 1994.

The main lesson of Beer’s book is that a female composer must be exceptional: exceptionally talented, exceptionally driven and exceptionally lucky. For many of them, it was a question of being born in the right place at the right time. Lili Boulanger and Maconchy, for example, benefited from writing during the first and second world wars, respectively: a country at war was a country that cared more about the nationality rather than the sex of its composers. Caccini and Marianna Martines were both lucky enough to have come of age under female rulers: specifically, female rulers who, at a time when “powerful women” was an oxymoron, chose to bolster their claim to power by surrounding themselves with other impressive women. And, of course, as Beer notes, for the mothers among them, “simply to survive childbirth [was] a statistical break”.

But for all their luck, this book does remain, in many ways, a catalogue of injustice. Women were restricted in the forms they were able to write, which in turn restricted their public reach and their legacy. Large orchestral works, so crucial for the development of a composer’s reputation, were usually off limits. Even by the 20th century, Maconchy’s ambition was curtailed by publishers such as Leslie Boosey, which “couldn’t take anything except little songs from a woman”. Women who persisted in writing did so “under the shadow of the courtesan”: of Martines, Beer notes that her “conservatism and caution in both her life and work… merely served to compound the constraints upon her as a woman and composer. And yet, paradoxically, Martines only achieved what she did achieve as a composer precisely because she remained scrupulously, rigidly, relentlessly proper.” And what did Martines achieve? “Everything that was open to a woman of her rank and station.”

The catalogue of injustice carries through into musical scholarship. Beer recounts the experience of Professor Marcia Citron, who in 1979 was attempting to research Fanny Hensel’s work in the Mendelssohn-Archiv in Berlin. At the time, it was under the directorship of a rather eccentric man called Rudolf Elvers. There was no library catalogue of Hensel’s holdings. Rather, Elvers informed scholars what they were (or were not) allowed to see. His hostility to her research was made explicit nearly a decade later when he said he was “waiting for the right man to come along” to research Hensel, rather than the “piano-playing girls who are just in love with Fanny”. He couldn’t see the appeal, personally. “She was nothing. She was just a wife.”

Thankfully, Citron persisted, just as the female composers she researched persisted before her. And although Beer is open to the limitations of writing about music (quoting Maconchy, she says it is “as if one sought to paint a smell”), luckily she has persisted too. Because one of the greatest wrongs done to these exceptionally talented women, who in many cases achieved international renown in their own openly sexist time, is that they have one after another been forgotten. Beer’s meticulously researched book is a vital step in the battle to overturn that ultimate injustice.

Sounds and Sweet Airs is published by Oneworld (£16.99). Click here to buy it for £12.99

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion