As a military campaign against Boko Haram continues in northern Cameroon, leaders of the country’s biggest mosques in the south are deploying another weapon to ensure that the Islamist insurgency doesn’t spread: education for girls.

Militants started to spill over the border from northern Nigeria three years ago, and while their attacks and recruitment drives remain contained to the far north region, imams in the Cameroonian capital, Yaoundé, are taking no chances.

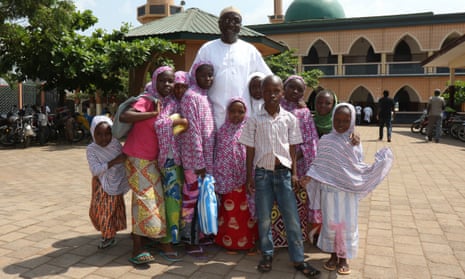

Mohaman Saminou, director of the Grande Mosque in Briqueterie – one of the city’s poorest and predominately Muslim districts, is providing free education for girls every weekend because he believes they are most at risk of being radicalised. “They can be influenced more than boys as they go for love or for money,” he says.

Dr Souley Mane, a professor and assistant imam at the Essos mosque, agrees that education is the most important tool in the battle for ideas. “In Cameroon we have a problem with the [low] numbers of girls in education, but it’s worse in the Muslim community as the parents don’t always understand its importance,” he says.

Mane adds that it is crucial western education is taught alongside Islamic studies. “Boko Haram says Muslims shouldn’t go to western schools. But no, Muslims need to study science and information technology to contribute to the development of our country,” he says.

“Western values and Islam are very, very compatible,” he adds, citing London’s first Muslim mayor, Sadiq Khan, to illustrate his point. “If I was ‘against the west’ I wouldn’t use this computer, this mobile phone,” he says, pointing around his house.

At Saminou’s mosque, the girls are taught computer science, alongside the Qur’an and sewing. As the Guardian is shown around, a young girl runs in to the room and declares that her favourite subject is the Qur’an. “She’s lying – it’s actually computers,” laughs her teacher, Dsaratou Oumarou.

There is also a modernist attitude in the school attached to the Yaoundé Central Mosque, the capital’s largest. Here students are taught in French, English and Arabic, with posters around the building promoting “bilingualism as a gateway to quality education and sustainable development”.

The classes are split by gender to “boost productivity”, with the girls outperforming the boys academically, says the education director, Hassan Mohamed. “An educated population doesn’t give away to extremism, so Boko Haram have very few opportunities,” he adds.

If education is Saminou’s first priority, his second is religious cohesion in the country, which is 70% Christian and 20% Muslim.

He allows Muslim women to marry men of other faiths in his mosque and says that most of the government security forces that guard Friday prayers are Christian. “For me it’s symbolic, we come to pray and the Christians make sure we are safe. Perhaps there is another place like this? But I’ve never seen it,” he says.

Despite the problems in the north, these religious leaders regard Cameroon as a country at peace and none recognise the religion that the militant group preaches. “They are killing everyone, Muslim and Christian, they are killing people in mosque in the market,” says Saminou.

Mane says: “Boko Haram is not Islam, Islam is not Boko Haram,” adding that “we ask the almighty to help with the security situation”.

The professor, who has published a book on the Boko Haram threat in Cameroon, says cooperation with government security forces is also vital and that uncover agents are present in most mosques to monitor what is happening in the community.

Despite fears of a potential attack, Mane is confident that there is no current threat in the capital. “No one has come in to the mosque with a bomb. The situation is changing positively, even in the north things are getting better,” he adds.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion