Updated | It began with a tweet, as so much does these days. The first shot in the coming war was fired in a 140-character burst by Shervin Pishevar, a venture capitalist in Silicon Valley. "If Trump wins I am announcing and funding a legitimate campaign for California to become its own nation," said the first in a volley of tweets by the Iranian-American technology investor. "As 6th largest economy in world," he said three tweets later, "economic engine of nation, provider of a large % of federal budget, California carries a lot of weight."

This call to arms was retweeted thousands of times in those bewildering first hours of the Age of Trump. By the next morning, the movement for California to secede from the United States had made national headlines, with Pishevar anointed the movement's leader. It even had a name, Calexit, an echo of the Brexit movement, which will eventually cleave Great Britain from the European Union. The nativist tone of Brexit foreshadowed the xenophobia of Donald Trump. Calexit is a kind of nativism too, except it's fundamentally sunny in disposition—a Brexit for American liberals much more closely aligned with Western Europe than West Virginia.

Unrelated to Pishevar's tweetstorm was a Sacramento rally held the day after the election (but planned long before) by Yes California, a secession group run by a young man from San Diego named Louis Marinelli. Marinelli, 29, wants to use California's ballot measure process to have his fellow citizens vote for secession, much as they have voted to ban plastic bags and legalize recreational marijuana. Unlike Pishevar, whose secessionary tweets were plainly fired off in a fit of frustration, Marinelli has been long at work on this issue and will eagerly lay out his reasoning to anyone willing to listen. "America is a sinking ship, and the strongest position for California to take is one on its own lifeboat setting its own course forward," he tells me. "A strong California holding its ground and attempting to influence the decisions of those in Washington at the helm of this sinking ship will find itself at the bottom of the ocean with them."

Even if the majority of Californians vote for Marinelli's proposal, peaceful secession from the United States would be nearly impossible, says just about everyone with a knowledge of our federalized system. Pishevar seems to have decided as much; in the days following the election, he backed away from his call for secession. Once ringing with secessionary bravado, his Twitter feed is now protected. A press representative tells me Pishevar wasn't going to discuss the issue.

Yet there are substantive differences between California and the rest of the nation, a contrast that will only become sharper over the next four years. The Rust Belt gloom that helped elect Trump feels so distant from the Left Coast that it may as well be an abstraction. The America you see from the Sierra Nevada foothills, the endlessly fertile farmlands south of Sacramento and the coastal ranges of Santa Barbara is really a very good place to live: efficient, inclusive, optimistic—America 2.0. Back when the notion of a President Trump still seemed preposterous, the state's Democratic governor, the gruff Jerry Brown, told a group of labor leaders in Sacramento, "If Trump were ever elected, we'd have to build a wall around California to defend ourselves from the rest of this country." Brown quickly added that he was joking, but we all know what Freud said about the honesty that humor frequently conceals.

It's true that Californians' love of their state can blind them. The famously beneficent West Coast sunshine hasn't been distributed evenly across the land; California's most persistent problems include high unemployment in the desert along the Mexican border and in the rugged, rural northlands, as well as a growing wealth gap along the prosperous coast, especially in the Bay Area, which competes with New York City as the most expensive place to live in the nation. The opioid crisis along the Oregon border is as serious as in the Midwest; the state's eternally underfunded public schools routinely rank as some of the country's worst, along with those of the Deep South.

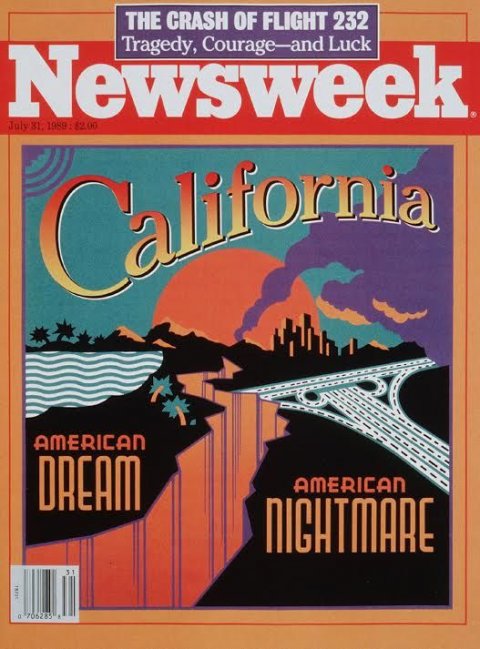

Yet for all those genuinely pressing problems, not all that long ago, the state was a full-blown disaster, to use one of Trump's favorite words. It was rancorous and dysfunctional, the right wing's favorite example of liberalism gone mad, not just a state with problems but a problem state. A 1989 cover of Newsweek showed California cleaved in two, a beach on one side, a clogged highway leading to a smog-smothered city on the other. The cover line: "American Dream, American Nightmare."

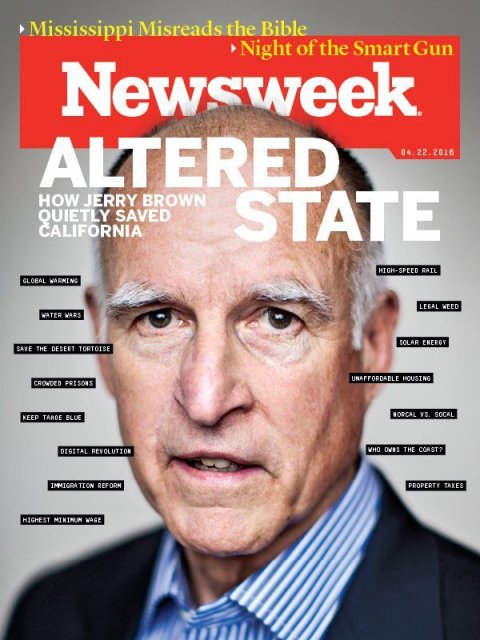

Today, cracks about Golden State dysfunction would be as dated as Woody Allen's quips from Annie Hall about the cultural vapidity of Los Angeles. Led by the proudly parsimonious yet reliably progressive Brown and bolstered by the economic hothouse that is Silicon Valley, California has become the sixth biggest economy in the world. (If Brexit hurts the British economy as much as some think, California could soon be fifth.) Californians pays $452.8 billion in federal income taxes to Washington, eclipsing second-place New York by $150 billion. It grows more food than any other state, produces most of the technologies we've become reliant on and, for better or worse, dictates what we watch in the after-dinner hours. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, California has more electricity-generating solar plants than the rest of the nation combined. About 85 percent of American wine comes from California, as does 100 percent of the Kardashian clan, whose members are estimated to be worth a combined $339 million—that is, about the gross domestic product of Micronesia. Not content with all these riches, California could soon eclipse Wisconsin in the production of cheese.

California's return to greatness didn't require border walls or trade wars. Instead of rolling back environmental regulations to curry favor with corporate interests, California has passed the toughest green laws in the nation, the first of them championed by Brown's predecessor, Republican Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. The state's citizens have voted in measures to increase taxes, legalize marijuana, restrict the rights of gun owners and enact criminal justice reforms. While conservative state legislatures are debating pointless "bathroom bills," California has passed what some say are the strongest LGBT protections in the entire world. The state hasn't found a remedy for earthquakes, but a company in Silicon Valley has what appears to be a workable solution. It involves houses that hover.

What California most definitely did not vote for is a reality-TV huckster pitching grievance-fueled xenophobia and a soot-covered energy portfolio borrowed from the 1950s, not to mention that decade's social norms, "pussy grabbing" and all. Though not much went right for Democrats on November 8, they crushed it in California, which Hillary Clinton won by 4.3 million votes. California Democrats also won a supermajority in the state Legislature, making it only one of six states with a Democratic "trifecta," meaning both chambers of the Legislature and the governor's office belong to the same party (Republicans, by contrast, now have 25 trifecta states). That effectively ensures the passage of most progressive legislation. Kamala Harris, the state's attorney general, was elected to the Senate, a victory many believe she will use to launch a presidential run in 2020 or 2024; voters approved measures reinstating bilingual education, legalizing marijuana, instituting background checks for ammunition purchases and increasing the tobacco tax, as if working off a wish list from the editors of The Nation.

What frightens Californians most about the next four years is that, instead of trying to learn from their state's successes, Trump could seek to extirpate the federal programs that even California needs to thrive. Trump (whose transition team did not respond to several requests for comment) opened his presidential campaign at his midtown Manhattan tower by invoking the image of Mexican murderers and rapists blitzing across our southern border. California, on the other hand, has the nation's biggest share of undocumented immigrants, 2.4 million, who are allowed to get driver's licenses and would have been allowed to buy health insurance (the state approved that plan but needed federal permission, which it declined to seek as Trump took office). Trump called Syrian refugees "a great Trojan horse"; California welcomed more Syrian refugees in fiscal year 2016 than any other state.

Trump also wants coal plants churning out black smoke and has even complained that environmental regulations eroded the quality of his beloved hairspray. Not only is hairspray passé in most of California, but the state was a major participant in 2015's climate change accord in Paris, which has most of the industrialized world working to curb greenhouse gas emissions. California expects to get half of its energy from renewable sources by 2030, with billions of public and private dollars going to wind and solar projects around the state. On the campaign trail, Trump railed against the Affordable Care Act. California is the nation's most enthusiastic participant in the Obamacare exchanges and expanded Medicaid coverage, with an estimated 5.2 million residents benefiting from some version of the ACA. Getting rid of the health law could cost the state as many as 334,000 jobs, according to a recent report by the Commonwealth Fund.

Although it's too early to tell what Trump will do on any of the above issues, Californians aren't waiting for him to land the first blow. In response to his victory, students at Berkeley High School walked out of class the day after the election, protesting on streets that hosted riots against Ronald Reagan when he was the governor of California 50 years ago. In Oakland, protests descended into violence, with parts of the downtown destroyed. On the Monday after the election, high school students walked out of Los Angeles schools, gathering at Mariachi Plaza, on the city's heavily immigrant East Side. One of them carried a sign more potent than all the tweets about California's hoped-for secession: "We are unafraid."

Speaking on his podcast a few days after the election, political journalist John Myers of the Los Angeles Times compared California to District 13, the heart of the anti-Capitol rebellion in The Hunger Games. The analogy leaves an intriguing question: Who will be California's Katniss Everdeen?

The What's-Left Coast

Gavin Newsom walked into the election night party being hosted by Senator Dianne Feinstein and looked up at a television screen. The polls had closed on the East Coast, and the former San Francisco mayor and current lieutenant governor of California watched the returns from Florida come in. Hillary Clinton had been widely predicted to win the state, but the map on the screen was mostly red. That was when Newsom knew that Trump had won. Though progressive measures supported by Newsom passed in California, he told me the results nationwide made it a "miserable evening."

An avid student of California politics, Newsom recognizes that Trump is a sui generis creature but also hardly the first Republican to hold the state in contempt. "The [George W.] Bush administration was hardly favorable towards California," he recently told me. He also pointed to James Watt, the rabid anti-environmentalist appointed to the Department of the Interior by Reagan. Governor Reagan, of course, gained national prominence by crushing protests at the University of California at Berkeley with a deployment of National Guard troops, which left one student dead. "We've been here before," Newsom said in a confident rasp that carried the slightest edge of belligerence. "We've not only survived, we've thrived."

Newsom, who many believe could be the state's next governor, is one of several mostly younger politicians expected to lead the Trump resistance. Another leader of that fight is sure to be Harris, the capable attorney general who in November won election to the U.S. Senate, becoming only the second woman of African-American descent to gain that distinction. Though she has sometimes been criticized for an overly cautious and calculated approach, Harris did not hold back when it became clear she'd won but would not be serving under a President Clinton.

"Do not despair. Do not be overwhelmed," she said, voice quivering, as she took the stage on election night at a nightclub in downtown Los Angeles. "When we have been attacked and when our ideals and fundamental ideals are being attacked, do we retreat or do we fight? I say we fight!" Her word choice—despair, overwhelmed, attacked, fight—suggested the early scene of an alien invasion flick, the bruised president rallying a terrified nation from the rubble of the White House.

In the trenches with Harris and Newsom will be Governor Brown, a 78-year-old who has fought enough political battles in his career to know how an impulsive, insecure neophyte like Trump can be tweaked. Feinstein, a proudly liberal native of San Francisco who sits on the Senate Judiciary Committee, is expected to frustrate Trump's attempts to appoint a right-wing ideologue to the U.S. Supreme Court. Southern California's Adam Schiff, who is the ranking Democratic member of the House Intelligence Committee, has been assiduously pursuing claims of Russian interference in the presidential election while criticizing Trump for his longing gazes at the Kremlin. Democrat Ro Khanna, a newly elected U.S. representative from Silicon Valley, invoked his Indian heritage and Gandhi's nonviolent resistance movement when asked by political commentator Randy Shandobil about legislating under Trump. "California," Khanna said, "has to be a laboratory for resistance."

There are also the state's Latino rising stars, including state Senate leader Kevin de León, Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon and incoming Attorney General Xavier Becerra, who could turn his office into a clearinghouse for anti-Trump lawsuits. At his address to the Assembly upon its return to work in early December, Rendon mocked calls for national reconciliation sounded by some since the election. "Californians do not need healing," he said. "We need to fight."

California's politicians sometimes squabble over the finer points of liberalism like medieval monks arguing over scripture, seemingly unaware that in huge swaths of the U.S., the mere suggestion of a plastic bag ban would be akin to declaring loyalty to ISIS. Their antipathy toward Trump is obviously ideological, but it is just as obviously calculated. A centrist Clinton presidency would have made it difficult for an up-and-coming liberal like Harris or Becerra to stand out; Trump practically invites incursions into enemy territory by a fearless progressive eager to defend the republic. Or for a veteran looking for one last great battle.

I believe #California has to be a laboratory of resistance, I will never be bullied by President-elect Trumphttps://t.co/w6aoPwYgpa

— Rep. Ro Khanna (@RepRoKhanna) January 11, 2017

Let's Play Chicken!

In the days after Trump's victory, California's popular and indisputably effective governor stayed quiet. Jerry Brown began his career in 1969, just as Trump, having evaded the Vietnam War draft, was starting out in his father's real estate practice. Brown has lost three presidential nominating contests, as well as one for the Senate, while winning nine California-wide elections, including a return to the governorship 36 years after first assuming that office. If politics is blood sport, Brown is incarnadine.

As his fellow legislators in Sacramento blasted away at Trump immediately after the election, the lifelong Democrat held back. That lasted, however, only a week. On December 14, Brown spoke to the annual conclave of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco. The scientific organization is not known for fiery rhetoric, but the AGU has openly stated its support for the science behind global warming. With the incoming president once dismissing climate change as a "hoax," a clash was inevitable.

Brown has made global warming the signature issue of his fourth (and final) term as governor. His predecessor, Schwarzenegger, had signed a law in 2006 mandating that the state drastically reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 2020. It was through Schwarzenegger's legislation that California eventually began its pioneering (if ultimately flawed) cap-and-trade program, which created a marketplace for trading carbon emission allowances. Brown has added necessary muscle to Schwarzenegger's green legislation, pushing the state to get half of its energy from renewable sources by 2030. Under his tenure, wind farms have taken root on mountain passes, while large swaths of desert glisten with solar arrays. Although California is not a nation (yet), it participated in the Paris climate accords in late 2015 and played a major role in the adoption of the Under 2 MOU initiative, which commits non-nation signatory entities (states, cities, et al.) to policies that will keep our planet from becoming one giant tanning salon.

Delivering what he would later say was his best speech since his presidential run (he didn't say which of the three he meant, though there's good reason to believe he was referencing his "Shape of Things to Come" speech from the 1980 campaign), Brown shredded Trump with glee. "We've got the scientists, we've got the lawyers, and we're ready to fight," he boasted of his state. "We're ready to defend. California is no stranger to this fight." In alluding to a potential diminution of the federal government's role in collecting atmospheric data, Brown said, "If Trump turns off the satellites, California will launch its own damn satellite. We're going to collect that data."

"This is one of the first speeches of the Resistance era that actually makes me feel better," wrote James Fallows in The Atlantic.

In articulating his defiance on climate change, Brown laid out a road map for California legislators who have their own disagreements with the new president: Resist by simply continuing to do what California has been doing; dare Trump to play chicken.

Myers, the Los Angeles Times reporter, convincingly argues that Brown could also be trying to set a trap for the Republicans by making them articulate their positions on climate change, thus exposing the absurdity of those views. For example, the apparent belief of Princeton-educated Texas Senator Ted Cruz that global warming is a conspiracy perpetrated by power-hungry liberals. Myers describes Brown's likely thinking as "We let it get to its most outlandish point, and then we're able to sweep in and get what we want by convincing the people in the middle."

Walling Off the Wall

For many of the state's Hispanic leaders, Trump is most threatening on immigration. Like most of his fellow Republican candidates for president, Trump promised to punish so-called sanctuary cities that do not cooperate with the federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency by handing over undocumented immigrants arrested for other crimes. Critics of sanctuary cities have cited the case of Kate Steinle, a San Francisco woman killed in 2015 by a stray bullet fired by Juan Francisco Lopez-Sanchez, an undocumented immigrant with a history of drug-related crimes who'd been deported from the United States five times. After a short stay in a San Francisco jail for a drug charge, he was released from custody without any notification to immigration officials. About two months later, he stole a gun from a federal official. A bullet from that gun killed Steinle as she was walking on the San Francisco waterfront with her father.

Steinle's parents have not supported Trump's immigration plans, yet he used their daughter's death as a lesson about liberal tolerance gone too far. "No more funding," he said during the campaign. "We will end the sanctuary cities that have resulted in so many needless deaths. Cities that refuse to cooperate with federal authorities will not receive taxpayer dollars, and we will work with Congress to pass legislation to protect those jurisdictions that do assist federal authorities." He may also get rid of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, a 2012 executive action by President Barack Obama that protected about 740,000 undocumented immigrants who arrived here as children from imminent deportation. Without the protection of DACA, these "Dreamers" would become what many of Trump's supporters have called them all along: "illegals."

The killing of Steinle, tragic as it was, didn't temper Californians' conviction that their state should be the nation's foremost haven for undocumented immigrants. As the Los Angeles Daily News reports, "All 58 counties in California and most of the state's police departments...decline to honor any ICE requests to hold immigrants beyond their jail sentences." The paper also cites a Texas Tribune finding that California is by far the state least likely to cooperate with ICE. Shortly after Trump's win, Los Angeles announced it would create a $10 million legal-defense fund to aid undocumented immigrants in potential deportation hearings. San Francisco is considering doing the same.

To supporters of Trump's hard-line immigration stance, California's defiance is not legally defensible, since all 50 constituents of the republic ultimately answer to the federal government. But according to de León, president pro tempore of the state Senate, Trump cannot expect already overworked law enforcement agencies to also act as immigration officers. "Taxpayers pay their taxes to local police to protect and serve them, not to enforce federal laws," says de León, a San Diego native of Mexican descent who represents Los Angeles in Sacramento.

In a recent conversation, de León frequently deployed the states' rights argument used by red states when trying to resist the Obama administration: We do our thing, you do yours. California's desire to be left alone might be difficult to ignore, since it has one of the most robust and diverse economies in the world. In a recent WalletHub study of how much each state gives to and gets from the federal government, 17 of the top 20 "taker" states all went for Trump. By contrast, California was ranked 46th. Many of its tax dollars flow to poorer red states in the Midwest and South. That makes California a major funder of Trumplandia.

I asked de León where California and the Trump administration could work together. I expected he'd say infrastructure investment, the most frequent answer for dismayed Democrats wanting something to like about Trump, who has proposed an improbable $1 trillion infrastructure plan.

De León did not launch into a lament for California's roads and bridges. "There are a lot of very important issues that we can find common ground on," he said, without naming a single one.

The Apprentice Apprentice

Some worry that California's leaders are overly combative. Joel Kotkin, a public policy scholar at Chapman University, outside of Los Angeles, finds the notion of a California resistance ridiculous. "What, you're gonna wear a beret and carry a carbine around?" he says, his strong New York accent compounding his derision. "California has become a crazy echo chamber," he complains, describing its Democratic leaders as "Stalinist."

Kotkin lives in Orange County, the Republican stronghold south of Los Angeles that went for Clinton. So did much of the coast, where most Californians live. But Trump did garner 4.5 million votes in the state, a fact easily obscured by all the Bernie Sanders signs in Berkeley and Oakland. Trump's support came from inland and northern counties like Lassen (72.7 percent) and Modoc (71.8 percent), where the population is older, poorer and whiter than on the coasts. Some of the Central Valley went for Trump too, in part because he told its farmers that there wasn't really a drought (false) and that the region's hardworking growers were being denied water by environmentalists "trying to protect a certain kind of 3-inch fish." This was a criminal oversimplification of complex water-rights issues that must take into account both agriculture and the environment, but it handed Trump counties like Madera, Mariposa and Tulare.

"People don't really know how insane the regulatory environment is," Kotkin complains.

The notion that California is a laboratory for unfettered liberalism ignores the fact that until recently Republicans had plenty of influence there. They lost it by promulgating some of the policies Trump now wants to foist on the entire nation. Newsom notes that Trump's nativism has a precedent in Governor Pete Wilson's Proposition 187, passed in 1994. That law, writes Narda Zacchino in her new book, California Comeback, "was designed to cause as much misery as possible for undocumented immigrants and their families" by essentially shutting them out of all social services. "It was a disaster for Republicans," she writes, "who rode a self-righteous, nativist wave right into irrelevance." Wilson also signed California's notorious Three Strikes tough-on-crime law, rolled back affirmative action and deregulated energy markets, which in part caused the energy crisis of 2000. All of his right-leaning "reforms" are now regarded as disasters, and Wilson himself a sputtering coda to Republican rule of California.

Despite that, after the recall of Democratic Governor Gray Davis in 2003, Californians elected a bombastic celebrity running on the Republican ticket: Arnold Schwarzenegger. Schwarzenegger started off in true Trump style, calling his Democratic peers in Sacramento "girlie men." He then picked an immensely costly, and losing, battle with public sector unions and statehouse liberals, before softening some of his positions. The Great Recession of 2008 proved an unfortunate capstone to his two terms. Kevin Starr, the famed California historian who died earlier this month, declared that "California is on the verge of becoming the first failed state in America." It took regulation-loving, plastic bag-hating Democrats to rescue it.

In all this, Newsom sees a microcosm of the kind of overreach he says Republicans in Washington, D.C., are about to commit, on many of the same issues. "I'm beyond convinced that in the next 10, 15 years the Republican Party is in serious, serious, serious trouble," Newsom says. "I have no trepidation about the future of the Democratic Party."

He notes that while Trump has followed Schwarzenegger into government, Schwarzenegger has taken over Trump's hosting duties on The Celebrity Apprentice. In fact, Arnold and the Donald recently feuded on Twitter over both governing and ratings.

"Cautionary tale," Newsom says of a once red California that seems destined for a blue future. "They should pay a lot of attention."

If the Lawsuit Fits

California's best weapon if war does come might be one beloved by Trump: the lawsuit. The man who would likely do the suing is a relatively unknown Los Angeles congressman: Xavier Becerra. With Harris leaving for the Senate, the state attorney general's seat was open. Brown chose Becerra, effectively making him the top law enforcement officer in the nation's largest state.

Becerra, who is of Mexican heritage, wasted no time in letting his constituents know where he stood on the results of the presidential election. "If you want to take on a forward-leading state that is prepared to defend its rights and interests, then come at us," Becerra said. "I believe with this nomination I have a chance to let California know I got their back." That kind of confrontational rhetoric quickly led to suggestions that Becerra would become the national leader of the movement against Trump, with The Nation calling him "the most important appointment since the election."

As many have noted, Becerra could simply take the playbook of conservative attorneys general and use it for liberal causes like environmental regulation and immigration. The Nation found that Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott sued the Obama administration on 46 occasions, and while these suits only infrequently succeeded, "they have swallowed up significant time and energy and effectively provided an alternative governing philosophy." Abbott is proud that his work on the behalf of Texans consists of nothing more than ideological warfare: "I go into the office, I sue the federal government, and then I go home," he has declared. Oklahoma, meanwhile, launched many anti-Obama suits concerning environmental regulations. That state's attorney general, the oil- and coal-loving Scott Pruitt, is Trump's nominee to head the Environmental Protection Agency.

But though Becerra's new position might make him Trump's chief tormenter, when we spoke in early January, just days before the first of his confirmation hearings in Sacramento, he had somewhat softened his position on Trump. "I am not picking a fight with anybody unless they try to get in our way," he told me as he prepared to depart Washington. Becerra also told me he'd been in frequent conversations with Democratic attorneys general across the nation, including New York's progressive (and ambitious) Eric Schneiderman, suggesting a potential alignment of anti-Trump forces.

Becerra's confirmation hearing in Sacramento on January 10 was a crowded affair. Brown made an appearance to voice support for the "outstanding candidate," in a clear sign that he means to anoint Becerra one of the state's new leaders. The hearing that followed was conducted with a gravity demanded by the task of staring down Trump. Reggie Jones-Sawyer, one of the state assemblymen chairing the hearing, alluded in his opening statement to potential "bloodshed" in the battle against Trump.

The nominee positioned himself as a principled defender of California law. "If we've got rights, let's protect them," he said. When one of the committee members asked about protections for LGBT individuals, he assured her he would be "a pit bull" against federal encroachments.

Becerra won't be going it alone in the courts. Just days before, the state Legislature announced it was hiring former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder as a legal adviser. Holder, now at the powerful Washington law firm Covington & Burling, is expected to help lawmakers defend California against federal encroachments, at a cost of $25,000 per month (the initial contract is for three months). Some have decried the hire as unnecessary; others wonder if Becerra is being needlessly overshadowed by a more prominent peer in Washington.

Holder was not made available for an on the record conversation. But in a statement provided by Covington & Burling and attributed to him, the former attorney general cited "expertise across a wide array of federal legal and regulatory issues." The statement downplayed the unique, combative nature of the arrangement, stressing that Holder's would be a "convention role" that "the firm has played for many clients over many years." Maybe so, but it's unlikely he would have been hired by Sacramento if a President Clinton were preparing to take office.

The Price Ain't Right

For all the forces arrayed against Trump in California, the federal government has several relatively easy ways to punish a rogue state. "We're screwed," glumly concludes University of Southern California political scientist Sherry Bebitch Jeffe when I ask how she reacted to Trump's win. All the "California resistance" rhetoric aside, she argues convincingly that the state needs the federal government much more than many will acknowledge. It doesn't help, she says, that California did nothing for Trump, who carefully files away all instances of insult and injury. "We don't have much leverage right now," she says.

Political columnist Dan Walters of The Sacramento Bee has a more harsh assessment, accusing the state's Democratic leadership of "trolling for attention, even in the national media, with risk-free, vainglorious denunciations of Trump."

Perhaps a belligerent stance is not the wisest, especially given Trump's love of dealmaking. "The key question is, Who is Trump?" says Bruce Cain, a political scientist at Stanford University. He favors a cautious approach, as with a mole that may be a cancer but may also just be a mole. "If he really is a dealer, then maybe there will be deals that allow to California to go its own way. But if Trump is really a wannabe authoritarian, then California should lead the resistance movement. In that case, I am pretty sure most Californians would think resistance is worth the cost."

But while Trump may be a paper tiger, his White House is rife with hard-line conservatives who've long nursed extremist visions they finally have the chance to achieve. In a cruel irony, some of them are Californians, including political adviser Steve Bannon, who helped found the white nationalist website Breitbart in a Los Angeles basement and who has complained about the supposed preponderance of Asians in Silicon Valley; Peter Navarro, a professor at the University of California at Irvine who yearns to start a trade war with China; and Andy Puzder, the Orange County fast-food executive who opposes the kind of minimum-wage increase that has been approved in California. Very likely, the policymaking practiced by this cast will require not the art of the deal but the art of war.

Liberals are especially worried about Alabama Senator Jeff Sessions's nomination for attorney general. Sessions shares the new president's desire to deport undocumented immigrants, having proved himself an unwavering warrior for nativism. He helped kill the 2013 immigration reform bill, Capitol Hill's most earnest attempt at reform in recent memory. As attorney general, he almost certainly will install tougher immigration judges and try to cut off federal funding to sanctuary cities. "He's been very up front in saying he wants to see the law enforced," a former Department of Justice official told Politico.

Sessions is also an opponent of legalized marijuana, a major cash crop in Northern California. The November election brought the passage of Proposition 64, which paves the way for the legalization of recreational marijuana in California (medical marijuana has been a boom industry here for several years). Estimates suggest that tax revenues from sales of legal weed could be as high as $1 billion. "Billion" is Trump's favorite number, but Sessions is chasing something other than revenue. Last spring, he said the nation was desperate for "grown-ups in charge in Washington to say marijuana is not the kind of thing that ought to be legalized." He once said he liked the Ku Klux Klan, until he learned some of its members smoked marijuana.

I believe #California has to be a laboratory of resistance, I will never be bullied by President-elect Trumphttps://t.co/w6aoPwYgpa

— Rep. Ro Khanna (@RepRoKhanna) January 11, 2017

The Obama administration has operated under the 2013 Cole Memo, which instructs the Department of Justice to leave alone states that have legalized marijuana. Sessions could have his Department of Justice draft a new memorandum, one that ended the policy of looking the other way.

Another unknown is where, exactly, Trump stands on the Affordable Care Act. On the campaign trail, Obamacare was a favorite target of derision and rage, yet since his improbable victory, Trump has indicated he might want to keep parts of the law, which has provided health care to 20 million more Americans. At the same time, repealing Obamacare has been the foremost—the only, critics might say—legislative goal of congressional Republicans, and they can do so relatively easily, now that they control both chambers of Congress. Trump's nominee to head the Department of Health and Human Services, Tom Price, is a congressman from Georgia who has called the law "stifling and oppressive." An orthopedic surgeon, Price has proposed a detailed plan predicated on beloved Republican ideas like tax credits and health savings accounts.

The repeal of Obamacare would be disastrous for California, which has implemented the law as enthusiastically as any state in the nation. The state's version of the national health care exchanges, Covered California, has 1.2 million members, while its expanded Medicaid program, Medi-Cal, benefits 4 million residents. It receives $20 billion in federal subsidies for health care, and while it could try to keep its version of Obamacare in place without the federal law, that would be "out of the realm of possibility" because of its price, public health scholar Walter Zelman told the Los Angeles Times.

Punching Up

California and Washington are like two ancient oaks standing on opposites sides of a field, their roots intertwined deep beneath the ground. As Jim Miller of The Sacramento Bee recently noted, one-third of California's budget is $96 billion in federal funds for education, transportation and health. Moreover, the state has benefited from $47.5 billion in federal contracts. It is also home to 344,919 federal employees and 132,008 members of the military. So while it is true that California gives more than it gets, it doesn't exactly get nothing.

Scott Graves, the research director of the California Budget & Policy Center, a nonpartisan think tank in Sacramento, says Trump is a "credible threat" to California and outlines three federal programs it needs to survive: the Affordable Care Act, the CalFresh food program and Supplemental Security Income. Combined, these programs have roughly 15 million enrollees in California, drawing federal funding of close to $70 billion.

Graves says Washington could punish California by making such federal programs "block grants"—that is, rigid funding streams that don't swell with enrollment numbers or worsening economic conditions. The remaining obligations would have to be met by the state itself.

"As long as the economy is humming along, and Silicon Valley and the stock market are doing well, California's state budget will be in pretty good shape, assuming that federal funding remains intact," Graves says by way of reassurance.

Silicon Valley needs skilled immigrants. The Central Valley, meanwhile, needs farm laborers to do the jobs most Americans won't. California also needs China, which is a close economic partner: A trade war could cost the state an estimated $20 billion in exports alone.

On a recent rainy Tuesday afternoon in Sacramento, Brown unveiled the proposed 2017-18 budget for the state. The nearly 200-page document was dedicated to Sutter Brown, the governor's corgi, who had recently died. Above a drawing of a paw print, there was a quote, presumably from the first canine himself: "Save some small biscuit for a rainy day." This is an allusion to Brown's enduring determination to avoid being another tax-and-spend liberal. So while a budget of $122.5 billion is enormous, it is the product of cuts in several areas, including housing and education.

The room was full of reporters, and most of their questions were about Trump. "We are not going to get hysterical, but we are going to get prepared," Brown said of his readiness to meet potential federal cuts. He seems to think that much of the bluster of the Trump campaign will dissipate once the realities of governing set in. "There are already cracks in the Republican Congress," he said, in apparent reference to the Obamacare repeal, or the GOP's badly bungled move to end ethics oversight of Congress. He also called the incoming administration's denial of climate change a mere "pause" that won't change the growing consensus about what human activity is doing to the planet.

The day after Brown's announcement, I spoke to Graves, who called the budget "really restrained." Sacramento's progressive wing wanted Brown to spend more, as it usually does. And, as usual, Brown resisted their pleas. Graves thought this a wise position, citing "huge uncertainty about major cuts that could be coming at the federal level."

Californians who dread what Trump might do to their state can take small solace in the fact that he has shown he has few core values, and his position on almost any issue can fluctuate as wildly as San Francisco's weather. He might do all of the above, or none at all.

Love him or despise him, Trump could be good for California. Economists at the University of California at Los Angeles suggest he could bring a "massive fiscal stimulus" to a state whose coffers are already full. David Shulman, the UCLA economist responsible for that forecast, predicts "Trumponomics" could result in $20 billion more in federal spending on California's infrastructure, and another $20 billion in defense, likely going to Southern California's aerospace industry and to cybersecurity firms in Silicon Valley.

At a Manhattan press conference in January, Trump said he would have the "greatest computer minds anywhere in the world" working to "form a defense" against foreign hackers of the sort who broke into the email of Clinton campaign chairman John Podesta. That could signal a major investment in California companies like FireEye and Palo Alto Networks.

That's why I suggested to Newsom that he invite Trump to tour Silicon Valley. Perhaps he could visit Twitter's headquarters on Market Street and personally thank its founders for helping him win the election without having to rely on the allegedly dishonest mainstream media. The very impressionable Trump could leave San Francisco enthralled by the California way.

Newsom did not appear thrilled by this premise. "He's welcome to come out," he said drily.

Newsom, who is frequently discussed as a potential presidential contender, became famous for issuing same-sex marriage licenses in contravention of California law. Though eventually ordered to stop by the courts, he gained a reputation as a fearless liberal willing to put moral principle above the rule of law. I asked him what he learned from that experience. "You can play in the margins," he said, "or you can punch above your weight."

Marinelli, the impressively industrious Yes California secessionist, is certainly following that advice. In December, he opened an embassy of the Independent Republic of California in Moscow.

This story has been updated with the correct number of Democratic "trifecta" states and the status of a health insurance proposal for California's undocumented immigrants.