16 February 2017

Ancient cave reveals recent droughts in the Middle East were most severe for over a millennium

Posted by Lauren Lipuma

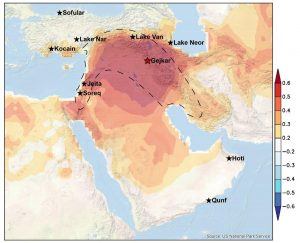

Map of the Middle East and Fertile Crescent (dashed line). Locations of currently available high-resolution and well-dated paleoclimate records (black stars) covering the last 2,500 years and Gejkar Cave (red star), where the stalagmite was collected.

Credit: Geophysical Research Letters/AGU.

By Pete Bryant

A stalagmite collected from a remote cave in the Middle East has revealed that recent droughts there were more severe than previously thought, and therefore possibly an important contributing factor for the turmoil in Syria.

A research team led by the University of Reading traveled to Iraq to collect the stalagmite and used it to present the first ever detailed climate reconstruction for the eastern part of Middle East’s most important region for agriculture – the Fertile Crescent – extending back 2,400 years.

The new and detailed rainfall record, published in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union, reveals that the catastrophic droughts in 1998-2000 and 2007-2010 were the most severe in around 1,100 years. The researchers also found the effects of these droughts were made worse by the climate having become steadily drier since the 10th century, something climate models failed to identify when simulating rainfall over the last 800 years.

“Using stalagmites formed below the Earth’s surface to study the climate above appears to be strange, but stalagmites are formed from precipitation above the cave,” said Dominik Fleitmann, an archaeologist and paleoclimatologist at the University of Reading in the United Kingdom and lead author of the new study.

“By taking measurements from the layers of minerals that form the stalagmite, changes in the amount of rainfall can be reconstructed from year to year back to several hundred thousand years,” Fleitmann said. “We found the recent droughts, in combination with the increasing demand for water in Syria and Iraq by a fast-growing population, created the perfect storm for societal turmoil. Our new and unique stalagmite record has also exposed flaws in the complex climate models currently used to predict droughts in the Middle East.”

The Middle East now has the largest water deficit in the world due to population increase, added water demands and climate change. The devastating droughts between 2007 and 2010 caused the displacement of more than a million people and have been argued to be a contributing factor to the ongoing Syrian civil war*.

Understanding the nature of droughts in this region is therefore vital to prepare for ongoing and future climate change, and to convince governments to prepare more effectively for future droughts. However, current knowledge about the frequency and duration of droughts is very limited, as meteorological records go only 50 to 100 years back in time.

Researchers collecting a stalagmite from Gejkar Cave in Iraq. Climate reconstruction using the stalagmite has revealed that recent droughts there were more severe than previously thought, and therefore possibly an important contributing factor for the turmoil in Syria.

Credit: University of Reading.

An international team, including palaeoclimatologists and archaeologists from the University of Reading, carried out nearly 25,000 tests on the 38-cm (15-inch) long stalagmite collected from Gejkar Cave in northern Iraq to reconstruct fluctuations in rainfall within the eastern Fertile Crescent (Iraq and Syria). The area, covering parts of Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel and Palestine, is where farming started and the first civilizations emerged several thousand years ago.

The team used state-of-the-art chemical analysis, including critical isotope measurements in Reading, to learn more about the timing, duration and severity of droughts in the recent past in unprecedented detail. Studying this data will allow them to learn how to better predict future climate in the region.

They discovered that the Middle East has experienced a long-term trend towards drier conditions, unseen by climate models and tree ring records, which began at the latest around 940AD. Comparing the data from the stalagmite with that produced by simulations showed they did not match, suggesting the climate models currently used to predict droughts may be producing inaccurate results.

The continuous decrease in rainfall coincides with a general decline in settlement density since the Medieval times, indicating that societies in the Fertile Crescent endured a long strife against climate.

“Unlike tree rings and current simulations, this stalagmite shows us the bigger and more complete picture about climate trends in the Fertile Crescent,” said Pascal Flohr, an archaeologist at the University of Reading and co-author of the new study. “It reveals droughts lasting several decades, which can have a cumulative and devastating effect on vulnerable societies. We hope that our results will help to improve our predictions and lead to a more responsible water management policy in the region to mitigate the effects of future mega-droughts.”

*The two droughts (1998-2000 and 2007-2010) in the eastern Fertile Crescent forced approximately 1.5 million people to move from rural areas into cities, where social tensions began to rise due to increased poverty. The effects of the droughts were amplified by very poor management and overexploitation of groundwater resources in the last 40 years.

—Pete Bryant is a press officer at the University of Reading. This post originally appeared as a press release on the University of Reading website.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.