Neuroscientists have used brain scans to spot the difference between people who committed crimes on purpose and those who broke the law through sheer reckless behaviour.

It is the first time that people’s intentions, or otherwise, to perform criminal acts have been decoded in a brain scanner, revealing that legal categories used to draw up sentences reflect real brain activity.

The researchers believe the work puts legal debates about criminal culpability on firmer scientific ground, but stress that it is not about to take over such decisions from the courts. The scientists could only decipher people’s intentions when they performed mock crimes while having their brain images taken.

“In most cases, when someone is committing a crime they are not doing so while inside a scanner,” the researchers point out in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The punishment a criminal receives can be profoundly influenced by their intentions when the crime is committed. If a person kills a family by driving into them, the penalty for doing so on purpose is much harsher than causing death through dangerous driving.

But while judges and juries must decide whether a person meant to break the law or not, it has never been clear whether the legal distinctions of knowingly committing a crime, versus doing so through reckless behaviour, are a true reflection of how the brain works.

“Other than dying of something, I can think of nothing more important than the categories that can deprive you of your freedom,” said Read Montague, a computational neuroscientist who led the research at Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute.

The researchers scanned the brains of 40 people while they took part in a computerised task that offered them rewards to carry suitcases across a border. On some occasions, the suitcase was known to hold drugs, but on others it was less clear. The scientists also varied the risk of the would-be smuggler being searched at customs.

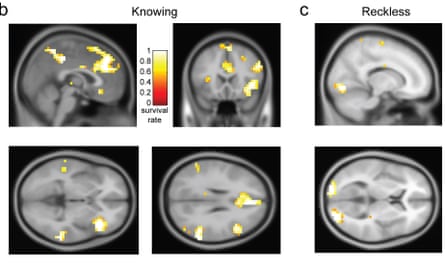

The scientists then set a computer to work on the brain images. Using an artificial intelligence technique called machine learning, the researchers found they could spot, with high accuracy, those who knowingly broke the law, and those who did so by simply taking a risk.

“You’re not going to do an experiment on someone accused of something and reconstruct a mental state last August and decide they were reckless instead of knowing,” said Montague. “But it’s a starting point for taking these sorts of things seriously and asking in what sense are these reasonable boundaries?”

Scientists will want to see similar scans from hundreds, if not thousands, more people before drawing any strong conclusions. With more brain images from people committing mock crimes, it should be possible to work out which areas of the brain are involved, and how differences in development, the drugs people take, and mental disorders, change brain activity patterns.

Writing in the journal, the scientists describe how future experiments might test whether a person’s mental state when they committed a past crime could be recreated by showing them pictures from the crime scene.

“Unless you were able to assess by fMRI the mental state of the accused at the moment of the crime it is unlikely to be useful in assessing the culpability of a particular defendant,” said Lisa Claydon at the Open University. But she said the research raised interesting questions about how we categorise criminal responsibility. If the findings are replicated in future work, such scans could help us understand how criminal categories equate to different levels of criminal culpability.

Paul Catley, also at the Open University, called the work “fascinating”, but added that while the research appeared to support the law’s classifications, the research did not explain how the different brain states influenced people’s behaviour. “The idea that in the future one could look back and find someone’s intention at the time of an offence seems along way off,” he added.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion