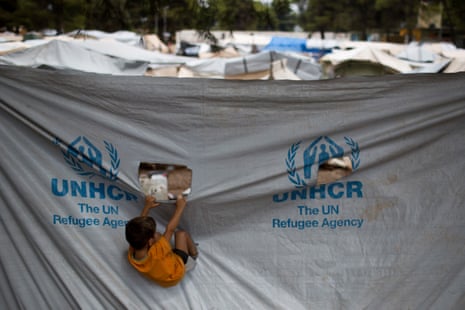

Urgent action is needed to help at least 23,000 unaccompanied child refugees stranded in squalid and unsafe Greek and Italian refugee camps, an official EU audit has warned.

Camp life in Greek and Italian “hotspots” – holding centres set up at migrant arrival points – is plagued by a lack of security safeguards, water, decent food, blankets and medical facilities, the new study says.

Claude Moraes, the chair of the European parliament’s justice and home affairs committee, described the report as “an alarm bell being rung” about the failures of EU states.

“The amount of child abuse, rape and smuggling that is going on is horrific,” he said. “If the EU is to have any sort of value it has to care for unaccompanied minors when they arrive in Europe.”

Reports indicate widespread child sexual exploitation in the centres, which Pope Francis compared to “concentration camps” over the weekend.

“Many unaccompanied minors have been held for long periods at the hotspots in inappropriate conditions, despite the law requiring that they be prioritised,” says the report by the EU’s Court of Auditors.

“The [European] commission should insist on the appointment of a child protection officer for every hotspot/site,” it adds.

EU states committed to rehousing 34,953 migrants from Italian camps but, by last September, had only made 3,809 formal “pledges” to do so and less than 1,200 actual relocations, according to the auditors. None were unaccompanied minors.

Catherine Woollard, the secretary general of the European Council on Refugees and Exiles, said that the EU’s treatment of lone children was “one of the most shameful aspects of the refugee crisis”.

“This report adds to a large volume of evidence about the exploitation and maltreatment that highly vulnerable unaccompanied minors are suffering,” she said. “Getting them to safety is now vital.”

While the EU’s hotspots approach improved the fingerprinting and security vetting of migrants, the auditors said that funding and relocation “bottlenecks” had extended the detention of migrants, with disastrous consequences for children.

Many slept rough or in unsegregated adult facilities with little security, surrounded by the constant threat of violence. On the Greek island of Chios, EU staff themselves had to be evacuated because of riots and aggression.

Hans Gustaf Wessberg, the study’s lead author, said that the accommodating and processing of unaccompanied infants in the hotspots fell short of international standards and needed “to be addressed as a matter of urgency”.

Children often travel alone to the camps from war zones in Syria, Afghanistan or Iraq, because their parents can only afford to pay for one family member to leave. But minors are also targeted by smugglers in the sex trade, according to Europol.

The law enforcement agency’s briefings suggest that a new surge in the number of refugees and migrants trying to reach Europe could begin as soon as June. More than 5,000 people lost their lives in the Mediterranean in 2016.

“We are about to see another wave in the crisis,” Moraes said. “It is partly seasonal and partly because of even more problems in Libya, the final movements of people from Syria, and because Turkey is creating pressure again.”

Almost 90% of the 2,500 child migrants in Greek hotspots come from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq. In the Italian camps, at least 20,500 children are predominantly from African nations affected by conflict and persecution, such as Nigeria and Eritrea.

Last year, only five children are thought to have been relocated to the UK from the hotspots under family reunion rules in the Dublin regulations.

“It is appalling that the UK did not sign up to the Dubs scheme,” Moraes said. “The UK showed a lack of leadership and solidarity in a refugee crisis that will affect both Europe and the UK.”