A combination of climate change, crime and market speculation has driven the price of vanilla to record highs, simultaneously damaging the quality of natural pods. Ahead of harvest season in the southern hemisphere, and summer in the northern hemisphere, the almost default ice cream flavor choice may not be as ubiquitous as usual.

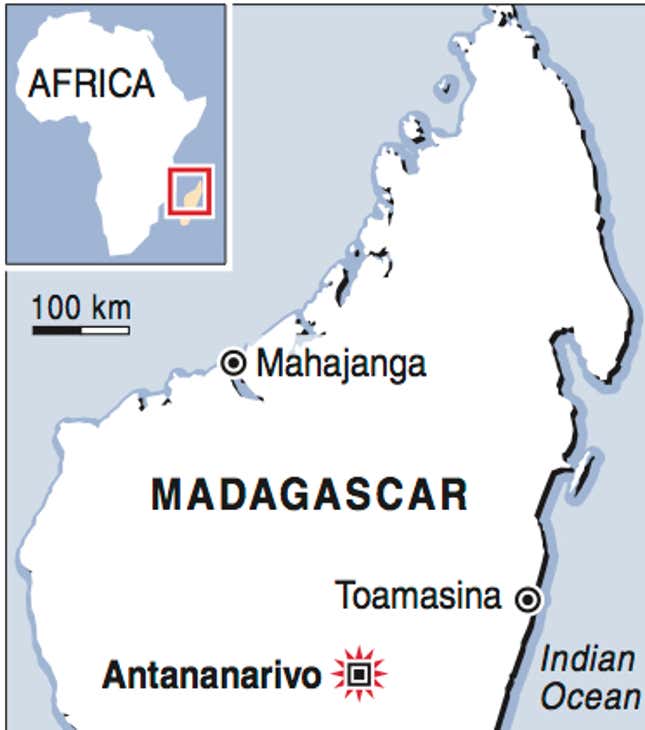

Vanilla is found in everything from ice cream to bourbon, but most of the world’s vanilla comes from one place, the island nation of Madagascar. This year, the island, located off the east coast of Africa, will produce 80% of the world’s vanilla, according to a Spring 2017 crop report (pdf) by Nielsen Massey, a US vanilla manufacturer.

As cultivating vanilla has grown more lucrative, India, Papua New Guinea and Uganda have planted more vanilla vines, with Indonesia the second largest vanilla producer. Madagascar’s dominance isn’t under threat yet—it could take five years for a new plantation to produce its first market-ready crop.

Yet, Madagascar’s vanilla production faces threats from within the island and far beyond its control. In March this year, Tropical Storm Enawo wreaked havoc in Madagascar, killing at least 78 people, displacing about 5,300 people and affecting nearly half a million people. The cyclone also damaged about 30% of island’s vanilla crop, which has already been affected by drought and desperate farming practices.

The uncertainly over this year’s harvest, set to start in June, has sent vanilla prices soaring. Vanilla prices have nearly doubled in the last year, and quadrupled in the last four years. In 2014, a kilogram of vanilla sold for about $60 a kilogram (just over 35 ounces). This year, the cured beans, the familiar darkened pod, are projected to sell at $400 to $450 per kilogram, a sharp increase from $225 to $240 per kilogram in 2016.

Vanilla exports should have helped make island life better and alleviate a poverty rate of more than 77%. Instead it has created a climate of fear and exploitation. DanWatch, a Danish investigative group, uncovered child labor and pitiful wages on Madagascar’s vanilla plantations.

The price increase has also attracted crime, with armed robbers ripping vines out of the ground. Farmers forced to sleep in their fields to guard their produce make only a fraction of the spice’s export price, according to the watchdog.

Desperation has driven farmers to pick immature green pods, which sell for about $80 a kilogram. Rather than 48 hours in a sweatbox and 90 minutes a day of sun-curing for two weeks and then aging in a wooden box for six months, the faster process relies on vacuum packing, which reduces the quality and yield of the sought-after mature beans.

The Madagascan government has gone as far as a public bonfire of the premature pods. They’ve also created a “vanilla platform” to regulate growers, exporters and the state to ensure a better product. Still industry leaders are doubtful that consumers won’t simply succumb to synthetic vanilla flavors.

“The 2017 Madagascar crop could very well be the worst quality crop delivered to the market in decades,” Aust & Hachmann, a Canadian vanilla distributor warned in May. “How can we advise anybody to buy historically poor quality vanilla at 25 times the price they paid for far better quality less than 5 years ago?”