Ramata Modou, 58, holds a photograph of herself. Ramata is community leader at an internal displacement camp for women and children in Mémé

When armed men entered Ramata’s village her husband suffered a heart attack and died. Her 17-year-old daughter was kidnapped, her three-month-old daughter strapped to her back. When she first fled to Mémé she slept under trees for two months with her six children.

She now lives in a camp for internally displaced women and children. All the women here have lost the men in their lives – husbands, fathers, brothers, sons – to the conflict. They built their own makeshift homes from sticks and thatch. There is a water pump but no sanitation.

Ramata holds her half-eaten lunch of ground red maize, white rice and crushed mango leaves. It is the only meal she and her children will eat today. The food was gathered by going house to house in the village to beg.

“Leaving my village was very difficult. We used to own cattle and sheep, but we had to leave all of those things behind. We had no choice, we had to leave. Even the roofs of the houses have now been stolen.”

People have fled violence in their village, often in the middle of night, leaving with nothing, sometimes not even their shoes. Those who arrive in Mémé are forced to rely on the kindness of new neighbours to provide clothes and food. Most families arrive with nothing, and even a battered spoon is a gift to be treasured.

- Remains of the daily meal for seven - ground red maize, white rice and crushed mango leaves. This plate is the half-eaten lunch of Ramata Modou, 58, and her family

- This battered spoon belongs to 20 year-old Amina, a young pregnant mother of two

Mahamat Blama, 27, a Cameroon Red Cross volunteer, stands outside a health centre in Mémé supported by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC)

The ICRC health centre provides free medical care. After an attack in Mémé last year the Red Cross built a high barbed-wire wall around the centre to protect patients and staff.

Many health facilities in the area close at 4pm, because it is too dangerous for staff to stay overnight. While the team here do a night shift, they still feel insecure and cannot sleep.

“I have been a volunteer for ten years,” Mahamat said. “Most of the children here are very thin – they’ve lost weight. I feel for them, but even the villagers here are affected because of the extra people in the community. I myself have four families living in my house. I share my food with them, we eat together. What do you do? If you have people in your house you cannot eat and they go hungry.”

Conflict in this area is having a direct impact on food. For the last four months, roadside crop growth has been restricted to one metre in height to protect towns from armed men, limiting the production of the most staple food products in this area: millet, sorghum and maize. Distribution of fertiliser, sometimes used as an ingredient for explosives, is also banned in this region. This, combined with a rainy season that now arrives two months later, sees agricultural livelihoods on hold, as land lies desolate next to the roadside.

- A plate of ground red maize, surrounded by a green sauce made from mango leaves

- A stick of red maize

Tchelou Bossomi, 20, with her 18-month-old daughter Khalfoumi, and son Abba, 4, in an IDP camp on the outskirts of Mémé

Armed men entered Tchelou’s village at night while she was asleep. Those who were outside were shot at, so they fled. Her brothers were killed and three teenage girls were kidnapped. Tchelou walked for two days to reach safety.

Tchelou said: “When we first arrived here we slept under trees in the village. Then people came and brought us to this camp. We have been here for nine months.”

“The major problem is food and the food that is given to us gets finished very quickly. We have to beg when the food gets finished. We never used to have to do that. Sometimes you have to put shame aside. You know you’re hungry, you know your kids are hungry.”

As more people arrive and food is scarce, prices have risen. It is onion season this month and some stalls in Mémé market have dishevelled red onions to sell. There is only one stall that sells tomatoes. This stall is divided into three sections based on quality. They all look battered and bruised – the majority are unidentifiable. The long-term effects of an unvaried diet, without fresh fruit and vegetables, sees children develop chronic malnutrition, with physical and mental stunting as a consequence. From Mémé market one red onion is 10 CFA (1p). Displaced families have nothing – so even this is an unaffordable price.

- Tomatoes - a luxury in Mémé, costing 160CFA (21p) for three at Mémé market

- A cracked bowl of food, containing a few grains of rice and some beans – the last few morsels of a lunch

Awana Abo Boukar, 50, holding a photo of himself with his two nephews, Al Hadji Dalla, 25, and Rawa, 15, in a dry riverbed in Minawao

Awana and his family left north-east Nigeria four years ago after conflict came to their village. They have been collecting water from this riverbed every day for two years. The rainy season now arrives two months late, which has exacerbated water scarcity in this area. Most people use traditional wells or dig dry riverbeds in search of water. This water is not safe to drink.

Awana said: “We left Nigeria because of the attacks. There were a lot of people killed. I lost my older brother. I brought all my family here.

“I have a family of 11: myself, my wife and nine children. We used to have four bags of rice a month to live on; now we only have two. We used to have more food, but not now. We have half the amount to live on. Even if I am worried, what choice do I have?”

- Niebe (black-eyed) beans. Found in the crack of a wall at Ali’s home on the outskirts of Maroua

- A bowl of fish bones for flavour. When you only eat one meal day, people look for anything to add flavour. A bowl of fish bones is all that remains of this meal. These small, brittle, dried fish are used to season bland staple foods, such as maize. These fish have almost no meat on their bones

Ali, 15, his mother, Amina, 50, and 80-year-old grandmother Aché Mal at a rented home in the outskirts of Mémé, north Cameroon

At 15 Ali is very small for his age, chronic malnutrition has stunted his physical growth and delayed his mental development.

Ali’s father was killed when armed men attacked his village. He fled, walking for two months and taking refuge along the way. He now shares a small house in Maroua, extreme-North Cameroon with his mother, grandmother, three aunties and 16 children.

His mother, Amina, said: “Food is our main hope as it’s the main problem here. Most of the time the children are sick.”

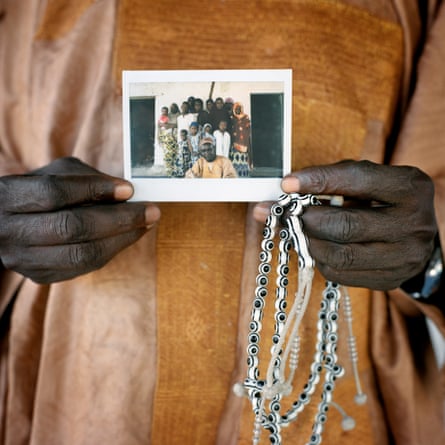

Ibrahim Sanda, chief of the village of Sarki holding a photo with 19 women and children he hosted in his home in Mokolo, north Cameroon

Originally home to 100,000 people, over 12,000 people have arrived in Mokolo during the conflict. Ibrahim Sanda is one of the many residents who have welcomed people into their home. He is currently housing 19 women and children.

Ibrahim said: “It’s important that people know they can come here. Since August 2014 people have been running here after the attacks in their village. There was no assistance for these people, so we brought them into our house.

“In the past I had one bag of maize to feed myself and my family. Now with all these people I need three bags of maize and it’s quite difficult for me. The costs are increasing. I need more money to support all these people.”

Climate change now sees the rainy season arrive two months late. Venturing into the wilderness to find wood is a huge undertaking in such a desolate area. Without the firewood, there would be nothing for people to sell to purchase food for their one meagre daily meal.

- This woven bowl contains maize husks. Food is so scarce here that even the chaff of maize is saved and eaten

- A piece of charred firewood. Firewood is an important commodity here. Not only is it used to cook, but people forage for wood in the bush and sell it in the village to earn money to buy food

Falta Oumara, 40, with her badly burned son Modou, 7, at an informal IDP camp for women and children in Mémé

Falta’s village in Cameroon was attacked in the middle of the night. The room where her children were sleeping was set on fire. One of her children died. Falta fled with her children that same night. Two of her sons aged seven and nine remain in hospital, while her seven-year-old son Modou suffered severe burns.

Falta now lives in an IDP camp with her children. She forages for firewood in the open bush to sell for money to buy food.

Fatimatou Amadou, 35 (Al Haj Boukar’s wife) and her nephew, Osman, 8, in a rented home on the outskirts of Maroua

Osman’s father was killed when armed men entered his village. Osman has malnutrition and has just returned from hospital. He is very quiet and lethargic.

Fatimatou said: “The food is not enough these days. In the night the children keep having stomach pains. They keep crying.

“Their temperatures rise. I do not eat well because of the children. I’m worried because when he falls sick I remember that he is an orphan and his parents are not here. Before we were eating three meals a day, but now we only eat when we can. I feel angry. I want the children to go to school so they can become something.”

- A sardine tin toy. Found in a rubbish dump, this tin is part of Aichadou and Ibrahim’s play kitchen. Pretending to cook dinner, the closest they now get to eating sardines is make-believe

- Small, brittle, dried fish such as this are used as a food seasoning. One small black plastic bag of seven fish costs 200 CFA from Mémé market.

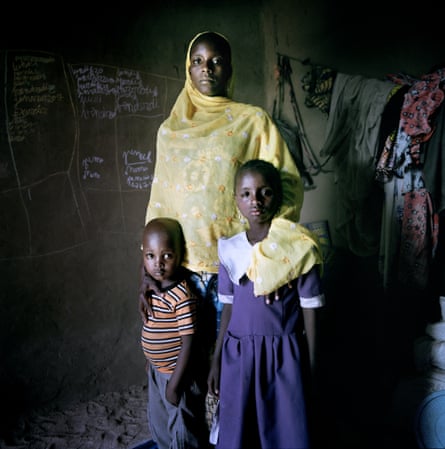

Aichadou, 6, with her heavily pregnant mother, Amina, and four-year-old brother, Ibrahim, at an IDP camp for women and children, Mémé

Aichadou and her family are Nigerian refugees living in the only permanent structure in the camp: a small, derelict, concrete outbuilding. Aichadou practises writing the French days of the week in chalk on the wall of her small home.

Amina said: “In the night they came. They took the village and said, ‘who wants to come with us?’ Those that didn’t want to come with them, they killed. I have not seen my husband since the attacks. I’ve had no news from him.“I may not eat, but not my children – they have to eat at least once a day. And if we don’t have anything, I go to the forest and take some leaves and eat those. All day all I can think about is my children – how do I feed them?”

Most people here do not have ID cards – they were lost or destroyed in the conflict. Securing a new one is very difficult, often requiring a birth certificate from one’s place of origin. Because of the conflict many places no longer even exist. Without an ID card, children like Aichadou cannot apply for a place at school and must make do with practising French on the wall of her house.

Sa Majesté Lougoumana Alhadji, local leader, Mémé

Situated about 30 miles from the Nigerian border is the village of Mémé. About 19,000 people fleeing conflict have arrived here, increasing the population to about 83,000.

Although peaceful now, the last attack in Mémé happened just over a year ago: a suicide bomb on market day injuring 112 people and killing 24.

The welcome and hospitality of Mémé, in particular from local leader Sa Majesté Lougoumana Alhadji, is so strong that people fleeing conflict will pass many other villages to reach here.

“Personally, for me this is very hard,” Sa Majesté said. “Some of the children live in tents, others are living in open spaces. Some of them are naked. These people cannot go back to their villages.

“We share our water. We share our food. This has increased poverty in the community. Unless we have an intervention, I don’t see a bright future for Mémé.”