Women who survived cancer in the past 30 years were a third less likely to become pregnant than women in the general population, according to study into the impact of the disease and its treatment on patients.

The research provides the first broad assessment of how cancer, the fertility-harming therapies that patients receive, and the decisions women make on leaving hospital, can affect their plans for a family.

“This really allows us to quantify the effects of cancer and its treatment, in the broadest sense, on women and girls having a pregnancy afterwards,” said Richard Anderson, professor of clinical reproductive science, who led the work at Edinburgh University.

The scientists analysed medical records for more than 23,000 women in Scotland who survived cancer after being diagnosed between 1981 and 2012. The cancer survivors had only 6,627 pregnancies, far fewer than the 11,000 or so expected for an age-matched group of women in the general population.

The impact of the disease was most striking for women who had not carried a baby before their diagnosis. The records showed that these women were about half as likely to conceive as similar but healthy women, with pregnancy rates of 21% versus 39%.

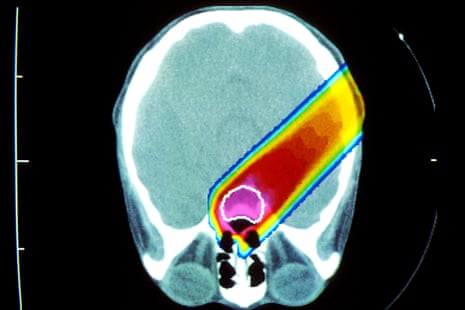

Many anti-cancer therapies are known to destroy fertility either chemically or through radiation, but many other factors will affect whether or not cancer survivors go on to have children. “As well as the treatment damaging their fertility, it’s also women choosing not to complete their family,” said Anderson. “Some women may not want to bring another child into the world when they are not sure about their own health.”

While the findings highlight the serious impact that cancer can have on female fertility and the choices women make around having children, the records point to a stark improvement in recent years, with some types of cancer now taking far less of a toll. In the 1980s, women who survived cancer were half as likely to conceive as others, but since 2005 pregnancy rates have risen to 75% of that seen in the healthy population.

Speaking from the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology in Geneva, Anderson said that doctors had seen clear improvements in pregnancy rates among survivors of some cancers but not others. For example, girls diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma today have far less radiotherapy than 30 years ago, causing less damage to their fertility. Similar improvements have not been seen in other cancers such as leukaemia, however.

The work highlights the need for more widespread access to new procedures that aim to preserve the fertility of girls and women who face cancer therapy. One approach is to remove ovarian tissue from the patient and freeze it until the patient has the all-clear and the tissue can be re-implanted. Last year, Anderson announced the first British birth using frozen ovarian tissue, to a 33-year-old woman who had part of an ovary removed 11 years earlier. Anderson said the latest findings should help doctors to counsel women who are diagnosed with cancer and direct services, such as ovarian tissue preservation, to where it is needed most.

Gillian Lockwood at Midland Fertility Services said that chemotherapy could add a decade to a woman’s reproductive age, an issue that must be taken into account in patient counselling. “A 30-year-old who has chemotherapy will have the reproductive potential of a 40-year-old, which is not good,” she said. “It’s important for these young women to know that even though their life expectancy – thanks to good, modern oncology treatment – is near normal, their reproductive life expectancy may not be as good.”

Nick Macklon, professor of obstetrics and gynaecology at Southampton University, said the results were positive for many cancer patients. “The knowledge that they can have a good chance of having a baby will be very important to women, and the addition of fertility preservation over the past few years has really changed the scene for them. Not so long ago, having a cancer diagnosis was seen as the end of your chances of having a baby,” he said.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion