A New Hope for Male Fertility After Cancer Treatment

An experimental procedure that regenerates sperm could ensure that men are able to have kids following chemotherapy.

When Branden Lischner was 18, he got testicular cancer. Between surgery and radiation, which can cause infertility, he saved a sperm sample. But he was so removed from the idea of fatherhood that he soon stopped paying for his banked sperm. Then, in 2013, shortly after he got married, his cancer came back. Lischner only wanted to worry about the surgery to remove his second testicle, but his urologist pushed him to take the time to store sperm.

Lischner saved three samples. On the way into the operating room, the urologist asked if maybe he’d try once more. By then, the insistence was annoying. But four years later, Lischner and his wife credit the doctor with giving them the family they didn’t know they wanted.

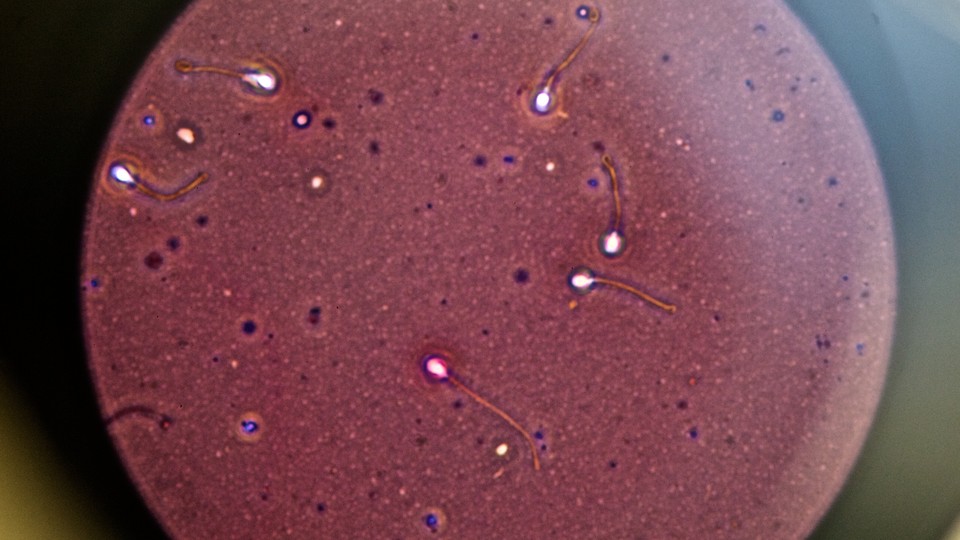

On average, men produce between 200 and 500 million sperm per ejaculate, although only a fraction of them reach the uterus. Lischner had only 13 sperm to work with. Joseph Sanfilippo, the director of reproductive endocrinology and infertility at Magee Women’s Hospital in Pittsburgh, estimates Lischner’s wife had about a one in 100,000 chance of getting pregnant. It really shouldn’t have worked. But it did.

While the Lischners got extremely lucky, researchers are now working on a new treatment that could help men like Lischner who didn’t save a sample before radiation, or even prepubescent boys who develop cancer and have no sperm to save. This experimental technique takes a sample of testicular tissue and turns sperm precursor cells into actual sperm cells. Put back in the testes, these sperm multiply, repairing normal sperm production. This holds the promise of allowing men who lose fertility through cancer treatment to have biological children not just in a lab, but the old-fashioned way.

* * *

Dylan Hanlon was diagnosed with Ewing’s sarcoma when he was 9. At first, the news overwhelmed his mother, Christine Hanlon. A busy lawyer and single mom near Tampa, Florida, she put his care entirely in the hands of his doctors. But after the treatment succeeded in preventing Dylan’s cancer from spreading, she started researching its short- and long-term effects. Furious that none of the doctors had mentioned a high risk of infertility, she did more research, and learned of Magee-Women’s Hospital’s experimental procedure.

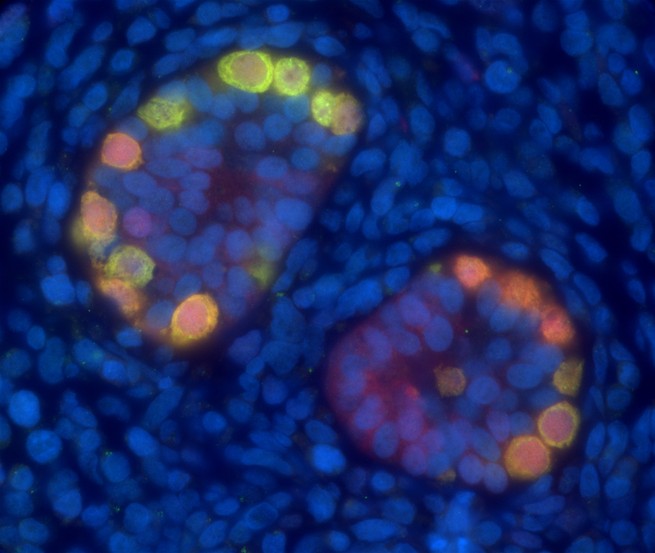

Hanlon was worried it was too late for Dylan after 12 weeks of chemo. Kyle Orwig, the head of the Fertility-Preservation Program at Magee, told her there was still a good chance Dylan had some spermatogonial stem cells. They’d do the procedure and check, and if they weren’t there, they wouldn’t save the sample.

Pioneered at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, spermatogonial stem-cell transplantation, as the procedure is called, was successfully performed on mice in 1994. Sperm are continuously created in adult men by turning spermatogonial stem cells into sperm. Prepubescent boys already have the stem cells, too; they just lack the ability to turn them into sperm. The technique collects a sample of stem cells, freezes it, and returns it to the testes. Although sperm precursor cells are damaged by radiation and chemotherapy, other cells in the testes seem to function normally after therapy. So putting the healthy, undamaged stem cells into the testis environment recreates the normal situation and promotes the nurturing of spermatogonial stem cells until they become actual sperm.

The procedure has since been done on rats, pigs, goats, sheep, and in 2012, nonhuman primates. Now, some fertility specialists are freezing testicular samples in the expectation of imminent human trials. At Magee Fertility-Preservation Program, doctors started freezing testicular samples in 2011. Although the exact amount of time these tissues can be frozen is uncertain, Orwig says there is “evidence in mice that stem cells can be thawed and transplanted to regenerate spermatogenesis after 14 years of storage.” Frozen eggs and sperm have been used to produce babies after decades of storage.

After consulting with Orwig, Hanlon talked to Dylan—alert and intelligent, it seemed to her, beyond his nine years. Dylan hated the chemo; he screamed and cried every time they tried to access his portal. He said more than once, “I don’t care if I die, just make them stop.” But he was enthusiastic about the experimental idea, according to Hanlon. “So I’d be a guinea pig?” he joked. She laughed and said yes.

Dylan’s doctors in Florida were not excited about the idea. Oncologists are concerned with saving the lives of their patients, and generally don’t want time and resources diverted from cancer treatment. If there isn’t a living patient, then fertility won’t ever be an issue. But Orwig contends that it was the right choice if Dylan was to have any chance of becoming a biological father one day.

* * *

Orwig sees it as his mission to disabuse doctors of the idea that thinking about fertility has to be a burden. Recently, he stood in front of a hospital conference room full of oncologists working within the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center health-care company system at their quarterly meeting, and explained a gap in care: His team estimates that they could do 1,119 fertility procedures a year, but they expect to do only 144 this year. Harvesting tissue need not delay treatment, he maintains; it can be scheduled to coincide with treatment-related procedures. And oncologists need not help patients decide whether or not to participate. They could merely present the option, give the Fertility-Preservation Program’s hotline number, and step back.

Orwig and his team give patients the option of saving a whole testicle or 20 percent of testicular tissue. The benefit of a whole testicle is that the team has more to work with, but the effects are more obvious. Taking 20 percent only appears as an indentation. In either case, the team keeps a quarter of each sample for future research.

What are the chances a successful procedure for restoring fertility will be available by the time Dylan, who’s now 16, is ready to have children? Sanfilippo and Orwig insist they’d never suggest the procedure to patients if they didn’t foresee progress. Orwig uses egg freezing as a comparable example: In 2011, it was experimental. Now it’s a standard of care. With childhood-cancer survival rates up to 85 percent, they see it as their responsibility to advance treatment.

Orwig also considers it his duty to educate doctors and to push men to think about infertility more generally. According to him, although a roughly equal number of men and women struggle with infertility—about 12 percent—fewer men think about fertility preservation. Their doctors talk less about it, too. Female fertility preservation is more complicated and costs more, both in the moment and in long-term storage fees.

Word is slowly spreading. In July, Donald and Jacqueline Renk took their son Paxton, not quite 2 years old, to the ER because he hadn’t urinated in 24 hours, and a tumor was found in his bladder. When they later sat with Paxton on a hospital bed waiting for his chemo—which his doctors are using to shrink the tumor because it’s too big to be removed—they told his doctor that fertility was the last thing on their minds. The doctor mentioned the procedure, but they were doubtful. He advised them to think about whether it might be worthwhile for Paxton to have the option in the future.

And Paxton has a future for his parents to consider. His cancer is predicted to be gone within a year. The oldest of Donald and Jacqueline’s four other children asked, “So he won’t be able to adopt kids?” When they said he would, he replied, “Well, then what’s the big deal?” Donald and Jacqueline loved that this is how their children think. And they decided that if Paxton might have the opportunity to have a biological child in the future and it wouldn’t delay his treatment, then there was really no reason not to do it. At the very least, they reasoned, his sample could help others.