It’s only a small corner of west London, but it speaks volumes about the recent history of the city. Inside a converted factory is the HQ of Stella McCartney’s design business. Two minutes’ walk away is a similarly refurbished building now owned and used by the photographer Mario Testino. Across the cacophonous link-road that connects the A40 to Shepherd’s Bush is the ever-expanding Westfield shopping centre. And looming over everything is an unspeakably unsettling symbol of the 21st-century capital and its awful inequalities: what remains of Grenfell Tower.

On the walls of a new local gallery are 50 or so black-and-white prints that vividly capture a decade-long experiment in different ways of living and tell a fascinating tale that would be inconceivable in the modern capital. It all happened 40 years ago, when 120 residents of a squatters’ community threatened with demolition, eviction and dispersal decided to fight back – by becoming a self-styled independent republic named Frestonia, attracting the interest of the world’s media and embarrassing the authorities into taking them seriously, and allowing many to carry on living here.

The photographer responsible is Tony Sleep, now 67. He came to the area in 1974, having become immersed in London’s thriving counterculture via work for a “hippie work agency” called Gentle Ghost – a kind of proto-TaskRabbit that offered help with everything from removals to cleaning services and charged people according to their financial situation. Well aware that “west London was where everything was happening”, he eventually gravitated to an address on Freston Road, W11, and was allocated a bed. In those days, squatting was a civil rather than a criminal offence (the law was changed by the coalition government in 2012), and across the capital an archipelago of squatter communities defined hundreds of lives.

“We never knew how long we were going to be here,” Sleep says. “It might have been six weeks, it might have been six months. We had no idea. If you’re in a squat, you’re there for however long it takes before the landlord says, ‘Go away.’” He ended up staying eight years, keeping a pile of bricks by his bed as a way of scaring off the would-be burglars who would regularly try and kick the front door in.

The group of people Sleep had joined lived in a clump of 19th-century houses that had been condemned around 20 years before due chiefly to all-pervading damp. Most of their residents had been rehoused on new high-rise estates, their former homes left empty. The area in which the houses sat was now a weird no-man’s land of car breaker’s yards, tyre dumps and businesses that were breathing their last breaths – the kind of place that could be used to develop an ad hoc community that lived largely outside the law.

Sleep’s photographs capture a mixture of young families, industrious bohemians – who included jewellery makers, car mechanics and one resident who made beautiful lutes – and people who evidently saw squatting as a means of doing nothing much at all. Rumours of imminent eviction, he says, would frequently fly around. And in the autumn of 1977, things got serious. At that point, the Greater London Council (the capital-wide authority abolished by Margaret Thacher’s government in 1986) served notice that the houses were to be demolished, the first part of a plan to turn the area into an industrial estate.

By this time, the squatters’ community included Nicholas Albery, an energetic product of 1960s hippiedom. Having organised a screening of the classic Ealing comedy Passport to Pimlico – in which the titular London neighbourhood declares independence from the UK – he suggested that the people in the GLC’s sights should do the same, an idea he had devised in collaboration with another hippie activist called Nicholas Saunders, and the poet Heathcote Williams.

“He presented it to us, like, ‘This is what we could do,’” Sleep recalls. “And everybody said, ‘You’re completely mad – why would we bother to do that?’ But that quickly became, ‘Okay – why not? We’ll go along with that.’ Nick did it all, really. It wouldn’t have happened without him. He was an extraordinary guy.”

In tribute to Freston Road, the new republic was to be called the Free and Independent Republic of Frestonia. It ceremonially seceded from the rest of the country on 31 October 1977, and appealed to the United Nations for help. The new nation had its own council of ministers, as well as its own stamps – which, when stuck to letters, often made it through the postal system. Visitors could have their passports stamped. Frestonia’s foreign minister was David Rappaport, an actor of small stature who would soon star in Time Bandits and who made it his business to talk to visiting journalists, often charging £50 a time.

“We found out we’d left the United Kingdom,” says Sleep, cracking a smile. “And it was a snowball that started rolling, and getting bigger. Normally, squatters had terrible, terrible press. But journalists found this really amusing. The tabloids loved it. They came down here and starting interviewing people, and before you knew it, it was a big story. Then as word got around, the streets started filling up with Japanese and Danish TV crews.

“The great thing about Frestonia being a joke was that it was non-threatening,” he says. “If we’d turned it into a riot, we’d just have got beaten over the head and thrown out. But the GLC found it hugely embarrassing: ‘Why the hell have you got all these people living in all these ridiculously empty houses that you’ve done nothing with, and why do you now want to turn it into a load of rubble and make all these people homeless?’”

Shelley Assiter was a young mother who had come to Frestonia after travelling around Europe with her husband and daughter. Soon after the declaration of independence, she recalls the GLC offering the squatters “hard to let” flats across London, an offer that some took up but plenty of others refused. “What was not acknowledged or honoured was the fact that we were a community,” she says. “They wanted to make us a non-problem: divide us, and scatter us to the four corners of Greater London. But all of a sudden we were in the news.”

‘A huge political victory’

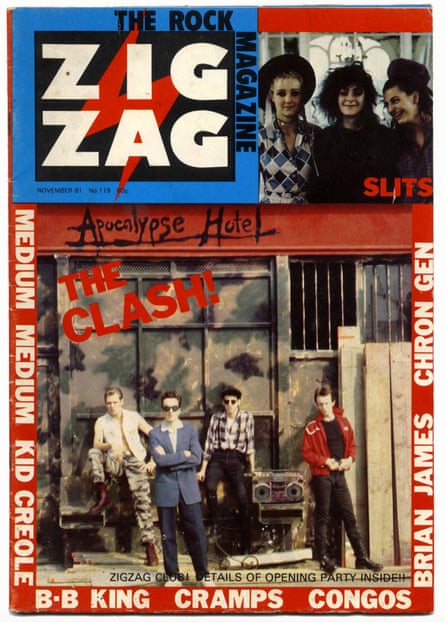

Life in the squats went on for another five years. At one point, scores of residents took the surname Bramley – Bramley Road was a Frestonian street – so as to try and appeal for rehousing as a family (it didn’t work). Meanwhile, the declaration of independence was a catalyst for a great burst of community activity, including the foundation of a Community Law Centre and an arts venue, located in the People’s Hall, a big Victorian structure that included a rehearsal space used by those famous west London desperadoes the Clash as they worked on 1982’s Combat Rock.

The GLC – led by a Conservative politician called Horace Cutler, who seemed to view the Frestonians with no little admiration – started to negotiate. Meanwhile, serious work had gone into the creation of a legally recognised housing co-operative, which was central to what the squatters were trying to achieve.

Everything came to fruition in 1982, when the co-op went into partnership with the Notting Hill Housing Trust on a new development, designed in collaboration with the squatters. Not everyone was interested. “Some people still wanted complete freedom, so they left at that point,” says Sleep. But many of the people who had been involved in the nascent republic signed up for new rented houses and flats.

Several veteran Frestonians – including Assiter, who now works as a psychotherapist and sits on the local housing management committee – still live in them. A Frestonia party takes place in their communal garden every year; the new art space displaying Sleep’s photographs is called the Frestonian Gallery. “As far as I’m concerned, this is still Frestonia,” says Assiter. “We still have an identity.

“And we won. We won big time, and it was a huge political victory. That’s the message we can still pass on: that there is power in numbers, and you can do things if you get together.”

Now, though, she has new fears about the future. As housing associations increasing resemble huge property developers, the organisation now called Notting Hill Housing has plans to merge with another provider to create a giant organisation in charge of 64,000 homes, which many tenants fear will make it far less accountable. Thanks to an ongoing drive to deregulate social housing, people are being pushed into a new, far more market-based reality in which there are different kinds of tenancy and various levels of rent – something Assiter says is anathema to Frestionia’s surviving ethos.

To cap it all, the government has plans to extend the so-called right to buy to housing association properties, which would mean that the homes built at the insistence of the Frestonians could simply blur into the increasingly gentrified neighbourhood that surrounds them and be thrown into the London property market.

“It all threatens the future of this place,” says Assiter. “When it was all starting to become clear, Tony and I wrote to each other and he said, ‘It sounds like Frestonia is in danger again.’”

She looks at me with the same expression of steely determination that must have defined the autumn of 1977. “And I said to him: ‘Frestonia is always in danger’.”

Welcome to Frestonia is at the Frestonian Gallery, London, until 11 November. Instagram: @frestoniangallery

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to join the discussion, and explore our archive here

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion