Forty years ago, Mohammad Ali Chaudry, a Pakistani-born economist, made his home outside New York City. He came for an executive job at the telecoms company AT&T, and ended up working there for decades. Like many immigrants to the US, Chaudry came to wholeheartedly believe – perhaps more fervently than his native-born neighbours – in the triumphal story that Americans tell about their nation: how it was always growing stronger through change, melding the many into one through the process of assimilation. Chaudry was a devout Muslim. But to him, it always seemed the things that made him different mattered less than the ways in which he had proved he was the same.

Chaudry and his wife, who is from Italy, raised three children on a street called Manor Drive, in the town of Basking Ridge, in the centre of the state of New Jersey. This is not the “Jersey” of popular imagination – the land of belching smokestacks immortalised in Bruce Springsteen’s working-class anthems. Basking Ridge is out in horse country, an area of rolling green hills and white-steepled churches, not far from Bedminster, where Donald Trump has his summer estate. In keeping with the values of his adopted community, Chaudry became an active member of the local Republican party and a conspicuous civic presence, running for various elected boards. In 2004, at the height of George W Bush’s war in Iraq, Chaudry became the first Pakistani-American to serve as mayor of a municipality in the US.

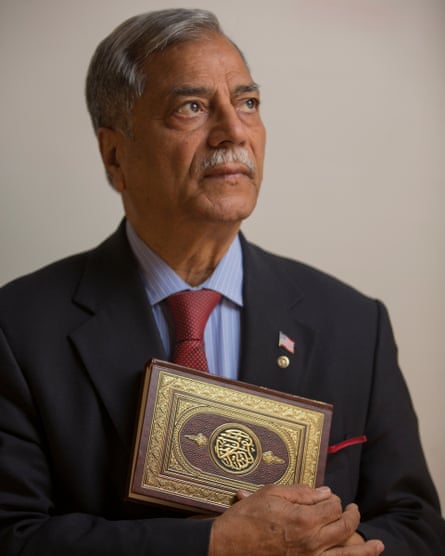

Long after Chaudry retired from both AT&T and electoral politics, he continued to keep a busy schedule of volunteer activities, most focused on building religious tolerance. He ran a small nonprofit organisation called the Center for Understanding Islam, and taught classes at local universities. Chaudry is bantam-sized, with a silvery moustache and a starchy manner, and despite his age – now 75 – he possesses a bottomless reservoir of diligent energy. He would travel the state, speaking to audiences young and old, always dressing the part of a politician, with a little American flag badge in his lapel. If there was prejudice around him in his adopted hometown, Chaudry later said that “it was not obvious, or visible, or overt”.

That changed in 2011, when he found a new cause: building a mosque in Basking Ridge. For years, Chaudry and other local Muslims had been using a community centre for a makeshift Friday service. But Chaudry decided that the Islamic Society of Basking Ridge needed a permanent place to pray, and he located what he believed to be a suitable site: a four-acre lot occupied by a rundown Dutch Colonial house. Soon after purchasing it, Chaudry held an open house to greet the neighbours. “There was not too much tension,” he said. “It was kind of jovial.” He put the letters “ISBR” on the mailbox in front of the house, to announce the Islamic Society’s arrival.

Then someone smashed the mailbox. “I was, of course, very surprised,” Chaudry said. Under New Jersey’s planning laws, the Islamic Society had to secure the approval of the municipal government to build the mosque, and from his experience as a public official, Chaudry knew that the town, which prided itself on its quaint homes and a history dating back to colonial times, was resistant to new development of any kind. But this was a house of worship, and he was someone well-known to the community. “It’s not that I was expecting any favours,” Chaudry said. “I expected them to be fair.” What shocked him, though, was the hatred.

That was seven long years ago, before some townspeople formed a group calling for “responsible development” in furious opposition to the mosque, before the 39 planning board hearings, before the mosque was rejected, before Chaudry filed a lawsuit alleging religious prejudice, before his lawyers uncovered racially charged emails among officials opposed to his plan, before the Obama administration accused the town of civil rights violations, before national rightwing activists took notice of the dispute and began smearing Chaudry as a terrorist sympathiser, and before Trump dragged anti-Muslim conspiracy theories from the disreputable fringes into the White House. Today, Chaudry knows his town – and America – better.

Long before Trump came along to capitalise on it, though, Islamophobia was building in the US, bubbling up like swamp gas from the depths. Often, racial conflict would manifest itself in small, seemingly isolated local planning fights over proposals to build mosques. The US Department of Justice, which staunchly defended the rights of Muslims during the Obama administration, noted a sharp increase in such mosque disputes between 2010 and 2016. Many took place in conservative locales such as rural Murfreesboro, Tennessee. But they also broke out in unexpected places such as Basking Ridge: a wealthy and well-educated community in the outwardly tolerant north-eastern US.

Basking Ridge is governed by a five-person elected committee, which meets in a repurposed Tudor-style mansion. (It previously belonged to John Jacob Astor VI, an American aristocrat whose father perished on the Titanic.) One evening last year, I attended a meeting – the first of many – at the town hall, where the committee members sat on a long dais, discussing their usual business, such as preparations for an upcoming celebration of the signing of Basking Ridge’s royal charter, in 1760. When the meeting was opened to comments from the public, however, all anyone wanted to talk about was Chaudry and the mosque.

“The neighbours near this proposed mosque did not sign up to live next to this house of worship,” said one resident, who broke down sobbing as she spoke. “They have been members of a quiet residential neighbourhood for decades, and do not look forward to having their routines and lives disrupted.”

The residents said the mosque would create traffic and commotion, and would ruin their property values. But they also complained about the tactics Chaudry had employed in his bitter court battle. One middle-aged woman gestured toward the mosque opponents in the audience, saying that many had been subjected to “a hateful harassment campaign” by the Islamic Society’s attorneys, who had served them with subpoenas seeking the contents of their personal email and social media accounts, in an effort to prove that they were motivated not by planning concerns, but animosity toward Muslims.

“Mr Chaudry has waged an expensive PR campaign that has talked about people as if they’re bigots,” the woman said. “And personally, I think it is the ISBR group that has been bullying and bigoted.” Then she invoked Trump, the inescapable presence. “They talk about our current president and how he speaks about Muslims. Well, I find ISBR’s rhetoric to be just as harmful.”

Finally, Loretta Quick, a schoolteacher who lived next door to the mosque site, got up to speak. She was one of the neighbours who had come to Chaudry’s initial open house years before. She had even voted for him, back when he was a politician. Now she was a die-hard enemy of the mosque. “If you cave,” she told the board, in a furious voice, “you’re saying that we are bigots, that we based the decision on discrimination against Islam.”

Quick was one of those who had been served with a subpoena, and was being represented by the Thomas More Law Center, an advocacy group that claims its mission is to defend “America’s Judeo-Christian heritage and moral values” against forces waging a “Stealth Jihad” to “transform America into an Islamic nation”. Quick referenced a recent press release the Law Center had put out, which had plucked a few verses from a searchable English translation of the Qur’an that could be accessed on the ISBR website – “Fight and slay the Pagans wherever ye find them”, etc – to suggest that Chaudry was somehow in league with religious extremists.

“These are words that seem quite intimidating and threatening to me,” Quick said. “I want to be protected, and you owe that to me, this township and this nation.”

How did a small-town property dispute turn into a religious war, with legal and symbolic implications for all of America? Part of the answer has to do with the country’s labyrinthine land-use laws, which leave most control to state and local governments, which are in turn vulnerable to the furies of angry mobs. Part of it has to do with America’s love of litigation. The inherently confrontational and intrusive legal process had a radicalising effect on the town, driving some opponents of the development to extremes.

But something else deeper and darker seemed to be at work. Some residents openly discussed Islamophobic conspiracy theories, such as the idea that the mosque was meant to send a message of conquest, due to its proximity to the town’s September 11 memorial. Such crackpot notions, promoted by far-right ideologues such as Pamela Geller and Frank Gaffney, used to be confined to the margins of the internet. Then Trump embraced the Islamophobes, unabashedly.

“It’s like his election has given permission to people,” Chaudry told me the first time we met. We were at the proposed site of the mosque, sitting in the old suburban house that he was still hoping to demolish. Its living room, dominated by a large stone fireplace, was filled with boxes of donated clothes that he was preparing to deliver to a family of Syrian refugees. The many bookshelves were lined with theological texts and stacked copies of a paperback that Chaudry likes to give out, Islam Denounces Terrorism. Standing on an easel in a corner was a poster-sized rendering of the proposed mosque. In an effort to make it fit into its suburban surroundings, it had been designed to resemble a mini-mansion, with gray clapboard siding, a pitched roof with asphalt shingles, dormer windows and minarets disguised as chimneys.

But the architecture did little to defuse tensions with the surrounding neighbourhood. Liberty Corner considered itself separate from the older and wealthier village of Basking Ridge, though they were both part of the same larger township, and few outsiders recognised the geographical distinction. And as even Chaudry and his allies admitted, some of the locals had a stubborn and ecumenical commitment to protesting anyone who dared to build anything, including Christian churches. People in Liberty Corner expressed an obstreperous ideology often abbreviated as “nimby”, for “not in my backyard”.

The opponents of the mosque told their own story of victimisation, in which they were merely objecting to Chaudry’s oppressive development scheme. “It was always about land use,” one Liberty Corner resident told me. “They made it about religion.” The nimby complainers claimed that the mosque site – a marshy plot on a mainly residential street – was a poor location for a busy house of prayer. When the township planning board took up Chaudry’s proposal in August 2012, signs soon appeared in front yards around town, reading “Preserve Liberty Corner”.

At one of the first planning hearings, a resident named Lori Caratzola stood up to challenge Chaudry. A law graduate, she cross-examined him about the size of the Islamic Society, accusing him of understating its membership. She revealed that she had done surveillance of a Friday service, counting 125 worshippers going into a space with a capacity for 60. After her confrontational performance, Caratzola became a leader of the opposition.

At the public hearings, Caratzola and others confined their criticisms to the nimby issues: drainage, parking, landscaping and the like. They convinced the board that a mosque would need more parking spaces than a church, because midday worshippers would come alone. When the Islamic Society submitted a new plan, with a larger parking lot, the mosque’s opponents protested that, too. It quickly became clear that the opposition was not solely concerned with parking.

Around the time the hearings began, some residents received an anonymous piece of mail. Inside was a letter entitled “Meet Your New Neighbor”, and a CD containing a recording of a radio interview in which Chaudry had offered some mildly nuanced opinions on Israel, Hamas and Hezbollah. “Here in Basking Ridge, on the surface, we see the serene, grinning academic Ali Chaudry, always willing to help us better understand the version of Islam he wants us to know,” the letter read. “Scratch the surface a little and an uglier picture emerges.”

The author of the letter tenuously linked Chaudry to the Muslim Brotherhood and the “Ground Zero mosque” – a proposed Islamic community centre in Lower Manhattan that Pamela Geller and Fox News had recently whipped up into a national controversy. It cited the term taqiyya, an obscure theological concept that Islamophobes often twist to suggest that Muslims are encouraged to lie about the true nature of their violent beliefs.

“So, welcome to the neighbourhood, Ali,” the letter concluded. “Let’s ask Ali about those Koranic verses regarding Jews and Christians in your Koran. Why are so many terroristic acts propagated by Muslims? Is it something they are taught in your mosques and at home? And what will you teach in your new Liberty Corner mosque? You wouldn’t lie to us, would you? Taqiyya is wrong, right?”

Just as the author of the letter accused Muslims of deception, the Islamic Society, in its lawsuit, alleged that many of the neighbours were presenting a false front, using preservationist sentiment to disguise their real, less respectable fears. “The key thing to remember,” said Adeel Mangi, an attorney for the Islamic Society, “is that these complaints are commonly used as a smokescreen.”

There is, literally, an anti-mosque playbook. Tactics were once unwritten, spread through websites and word of mouth, but more recently they were set down in a book titled Mosques in America: A Guide to Accountable Permit Hearings and Continuing Citizen Oversight. Written by a Texas attorney, it was published by the Center for Security Policy, an organisation headed by Frank Gaffney, a former Reagan administration official who has long espoused the theory that Muslims are engaged in a secret plot to impose sharia law on the US. Gaffney writes in the book’s introduction that it is a “how-to manual for patriotic Americans who are ready to counter the leading edge of Islamic supremacism”.

The manual offers lessons from cases like the one in Basking Ridge. “It may be startling to consider, but Islamists are entitled to exploit liberal free speech rights to advance their political and legal operations,” the author warns. It advises residents to express objections in the manner most likely to sway the authorities, avoiding mention of religious issues. “Concerned citizens must learn to express questions and reservations in a manner appropriate to the relevant civic forum’s purpose,” the manual says, instructing readers that “rather than expressing alarm as hysteria, speaking to local government officials and media requires a strategic response based on reason, facts, precedents, and the law”.

Sure enough, the transcripts of the dozens of hearings held by the town’s planning board, which run to nearly 7,000 pages, contain no mention of sharia, the Muslim Brotherhood or other rightwing hobgoblins. Most residents swore that religion had nothing to do with their opposition. But the Islamic society’s lawyers suspected – and would later allege in court – that their opponents were showing another face when they talked to each other on the internet. A commenter named “LC” – who appeared to be Caratzola – often expressed anti-Muslim sentiments when the mosque was debated on local web forums and national sites with names such as Bare Naked Islam. (Motto: “It isn’t Islamophobia when they really ARE trying to kill you.”) Caratzola was also listed as a member of a Gaffney-affiliated group set up to defend against the supposedly creeping influence of sharia on US courts. (“I stand by that,” Caratzola later told the New York Times, claiming that “every single terrorist attack in the last 20 years was committed by Muslims”.)

In December 2015, a few days after a Muslim husband and wife killed 14 people in a terrorist attack in San Bernardino, California, and shortly before candidate Donald Trump proposed a “total and complete shutdown” of Muslim immigration, the town’s planning board voted to reject the mosque.

At Caratzola’s urging, the town government also adopted a new ordinance that raised the minimum size of the plot required to build any new house of worship – which would effectively prevent the Islamic Society from building on its own site in the future. The Islamic Society quickly filed a lawsuit against the township, alleging the opposition was a “well-funded machine” that was “substantially grounded in anti-Muslim animus”.

The lawsuit particularly highlighted Caratzola’s role as a ringleader of the opposition. In a letter to a local newspaper, she accused the Islamic Society of “slander” – and invoked the concept of taqiyya to suggest that Chaudry’s mosque proposal was not what it seemed. “Many people and groups in the Muslim community,” she wrote, “are trying to quash what we so fervently cherish in America – the freedom of speech.”

The Islamic Society also claimed it had the constitution on its side – specifically, the first-amendment protection of the freedoms of religion and assembly. And Chaudry could call upon a powerful ally: Barack Obama. Under his administration, the Justice Department intervened on behalf of Muslims in many mosque disputes, including a highly publicised case in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, where the construction of a mosque was opposed with lawsuits, protests and an arson attack. It was able to rely on a powerful legal tool: a law, originally passed with bipartisan support in 2000, that specifically bans local governments from discriminating against religious organisations when it comes to land use.

The enforcement policy “reflected the fact that Islamophobia is a real problem across America”, said Tom Perez, who handled the Murfreesboro case as a director of the Civil Rights Division. (He is currently chairman of the Democratic National Committee.) “I think as you see the proliferation of social media, the world has gotten smaller,” Perez told me. “People who harbour these extreme views have a virtual platform to spread their hate.”

In 2016, the US Justice Department filed its own lawsuit, claiming that the local planning board violated the Islamic Society’s rights in rejecting its building plan. To Islamophobic activists, who spent the eight years of Obama’s presidency promoting conspiracy theories about his birth certificate and suggesting he was secretly a Muslim, such moves were yet more evidence of the administration’s suspiciously sympathetic stance toward Islam. “Islamic supremacists and Muslim Brotherhood organisations … called upon their running dogs at the Department of Justice to impose the sharia and usurp American law for Islamic law,” Pam Geller wrote in a blogpost about the Basking Ridge mosque case. “What small town can go up against the US government’s vast resources and endless taxpayer-funded muscle?”

The federal government’s intervention had a radicalising effect in Liberty Corner. The neighbourhood’s enemy was no longer a pushy former mayor; it was President Obama. Then, as if a Justice Department investigation wasn’t intrusive enough, private citizens started receiving knocks on their doors from people carrying subpoenas, seeking to probe their email and social media accounts. The Islamic Society’s lawyers – members of a prestigious Manhattan firm that was working pro-bono – wanted to prove that Caratzola was really the commenter “LC”, and that she and her allies were communicating their true attitudes to each other – and to their elected leaders – outside of the public meetings.

Understandably, though, the private citizens felt threatened by the intrusion. Their complaints attracted the attention of the Thomas More Law Center, which intervened on the behalf of residents seeking to quash the subpoenas, claiming that the demand would have a chilling effect on free speech. On its website, the Law Center decried the “outrageous unconstitutional intimidation”, alongside a heroic photo of Caratzola standing in front of an American flag. “Lori Caratzola,” the caption read. “Persecuted for opposing the mosque.”

On 31 December 2016, a federal judge issued a preliminary decision in the Basking Ridge case, finding that the planning board had exercised “unbridled and unconstitutional discretion” in requiring the mosque to have more parking than other houses of worship. Though the case was far from over, it was clear that the law favoured Chaudry. The victory rang hollow, though. Trump had just been elected president, giving a jarring rebuke to liberal values, and placing Muslim-Americans like Chaudry in a newly precarious position.

As a candidate, to bolster his call for a ban on Muslim immigration, Trump had often cited the research from the Center for Security Policy, Gaffney’s group. (“Very highly respected people, who I know, actually.”) Some of his most important advisers, such as Steve Bannon and Mike Pompeo, soon to be named the CIA director, were outspoken Gaffney admirers. Gaffney saluted the new attorney general, Jeff Sessions – the 2015 winner of the Center for Security Policy’s “Keeper of the Flame” award – for his vigilance “against all enemies, foreign and domestic”. With Sessions and other members of the nativist right in charge of the federal government, the Justice Department’s commitment toward protecting Muslims and their mosques looked shaky.

On a chilly Friday in April last year, still early in Trump’s presidency, I helped Chaudry as he performed his weekly ritual, carrying items from the garage of the old house in Liberty Corner to his gold Toyota SUV. In went eight rolled-up prayer rugs, then the plastic donation boxes, the folding music stand that serves as a lectern, the sound system, the digital clock, which was synchronised with Mecca, and four decorative mats, which Chaudry uses to slightly sanctify the drab walls of the community centre that the Islamic Society currently uses for its Jummah service. When the SUV, known as the “Mosque Mobile”, was full, Chaudry would drive it across town for prayers. “I’m just overwhelmed with everything that is going on,” he said as we got in the car. For the past few months, Trump had been fighting to impose his ban on travellers from seven Muslim-majority nations, sparking court confrontations and massive protests.

Chaudry was responding to the crisis with a characteristic burst of civic activity, participating in political forums and interfaith vigils. The relationship between Muslim communities and their government was wary at the best of times, and Trump was making it much worse, but Chaudry saw himself as a trust-building emissary. He served on advisory panels to law enforcement. A few weeks before, he’d spoken about discrimination and the travel ban at a worried meeting between Muslim leaders and many prominent New Jersey politicians. At the forum, as he did nearly everywhere he went, Chaudry promoted an earnest personal cause, asking everyone present to take a formal pledge he’d composed, to “Stand up for the Other”.

The Mosque Mobile turned on to Church Street, the main road through Liberty Corner. The neighbourhood traced its name back to the American revolution, and the whole town took great patriotic pride in the role it had played in the independence struggle, as a stronghold for George Washington’s army. Chaudry took a roundabout route, pointing out horse farms and new tract developments, and a park where the Islamic Society prayed when the community centre was used for a summer camp. “Where the flag is, this is the 9/11 memorial,” Chaudry said. “I was on the township committee when we did that. Eighteen people here died.” A wooded road took us into Basking Ridge. In the yard of its Presbyterian church, founded in 1717, stood an ancient tree known as the “Holy Oak”, where Washington is said to have picnicked with the Marquis de Lafayette.

At the community centre, we were joined by Chaudry’s wife, Victoria. We rolled out the mats and set up the speakers, and used a 30-metre (100-ft) sound cable to connect the small main room with an adjacent annex, which was used for overflow. Chaudry pointed, proudly, to his name on a plaque on the wall – he had helped to establish the centre. About a decade before, he and around a dozen other Muslims had started gathering there. But there were more Muslims around than he realised, working as doctors in the area’s hospitals, or as scientists in its many pharmaceutical firms, or as engineers at a big telecommunications company. The Islamic Society had long ago outgrown its temporary space.

The worshippers began to arrive, most of them men coming from office jobs, plastic ID badges hanging from their belts. They dropped their shoes in an unruly pile near the centre’s doorway, and used a cramped galley kitchen to perform wudu, the Muslim washing ritual. Then they knelt down as the muezzin sang a call to prayer.

Because it lacked a permanent home, the Islamic Society had no imam, and it relied on a rotating cast to lead services. This week’s visitor, Chaudry told me, was known as “the crying imam”. That week, dozens of Syrian civilians, including many children, had been killed in a poison gas attack, and the night before, Trump had fired cruise missiles in reprisal. The imam, dressed in a long black robe, led a prayer for “our brothers and sisters in Syria”. His voice trembling, he sobbed, “Give peace to this region.”

“That’s one of his characteristics,” Chaudry said after the service. “He does become emotional.” Most of the worshippers, who numbered around 70 in all, quickly returned to their cars and hurried back to work. Chaudry repacked the Mosque Mobile.

“I’ve been carrying these rugs for more than 10 years now, and I’m tired of doing it,” he told me. “We need to have a place of our own.”

As we drove out of Basking Ridge, Chaudry pointed out the Holy Oak, standing tall in the churchyard. The tree was rotten, he told me. Later that month, it would be cut down, and its dead branches handed out to townspeople as patriotic keepsakes.

Despite Trump’s election, Chaudry still retained his hope for justice, at least for his congregation. The case was now in the courts, which meant the Justice Department couldn’t easily abandon it. The town’s government, facing an almost certain legal defeat, was under pressure from its insurance company to settle its lawsuit with the Islamic Society quickly, before a trial.

Throughout the spring and summer of 2017, negotiations dragged on over a settlement, which would include a large damages payment to the Islamic Society. I attended endless meetings of the township’s elected committee, at which angry citizens would demand information from stone-faced board members, inveighing against the settlement in increasingly apocalyptic terms. Chaudry attended with other members of the Islamic Society. He sat in the front row but said nothing, keeping his head down and scribbling in a pad, showing no emotion even in the face of incendiary provocations.

The opponents were a surprisingly diverse lot. There were some old-money Protestants, who complained that the hubbub would bother their horses. But some of the most emotional speakers were new residents, many of them immigrants from south and east Asia. At one meeting, one of the Islamic Society’s closest neighbours, a medical professional from India who was building a large house directly behind the mosque plot, stood up and addressed the Muslims in the audience directly.

“If you are somehow able to get a mosque built, you will create a divide which you will not be able to bridge,” he said. “On the other hand, if the site would move to another appropriate location, you will earn our respect, and you will truly earn the right to build a mosque in this town. What is it that you want, to just build a mosque, or set an example for the whole country?”

By the perverse logic of the mosque opponents, it was the Islamic Society that had brought discrimination upon itself, by suing over discrimination. There was only one thing the Muslims could do to prove themselves worthy neighbours: go somewhere else.

It wouldn’t be fair to say, though, that everyone who spoke against the mosque was religiously motivated. Many, if not most, of the adversaries appeared to be genuinely impassioned in their opposition to development in Liberty Corner. “Sure, there’s a 5% lunatic fringe,” Paul Zubulake told me one evening while sitting on a bench outside the town hall, waiting for yet another meeting to begin. But he said that for him, and many others, religion was beside the point: “It’s about our quality of life. It’s going to destroy our community.”

To show me what he loved about Liberty Corner, Zubalake invited me to visit his home, a few doors down from the Islamic Society property. When I arrived, on a rainy Memorial Day in late May, a soggy town parade was making its way down the main thoroughfare, Church Street. As Zubulake was introducing me to his family – explaining that his son has autism, and they had moved to the area for his schooling – he spotted the mayor marching by with other members of the township committee. He dashed down to the roadside and shouted: “There’s still time!”

The politicians frowned and kept marching down Church Street. “I just want them to know how pissed off I am,” Zubulake said.

Chaudry, meanwhile, had organised a contingent from the Islamic Society to march in the Memorial Day parade. They met in front of the house, next to a sign that Chaudry had staked in the yard, reading: “Proud to Be An American.” Whether by chance or intention, the parade’s organisers had put the Islamic Society at the very rear, right behind another marginalised group, the local Democrats. Chaudry coaxed the children who were marching with the Islamic Society’s banner to stay in a tight formation. “Good morning!” he called from beneath a big black umbrella, waving an American flag with his free hand. The parade route ended at a war memorial, where Chaudry left a wreath with a mosque insignia.

“My advice to the community has always been that this is not the time to hide,” Chaudry told me later. “You have to be out there, fighting for your rights.”

To some people in Basking Ridge, Chaudry’s struggle looked less noble. They saw his battle with the town government as a local political feud, which dated back to his tenure as an elected official, long before he ever proposed the mosque. Chaudry had first run for a seat on the town committee in 2001. After September 11, which hit the commuter town hard, he told the local newspaper: “We are all under attack.” But a Republican party leader called him to suggest it might be better if his campaign signs, which read “Ali Chaudry”, just used his last name. “I said everyone knows who I am,” Chaudry told me. “I’ve never kept it a secret.” He won the election. But he was not universally popular.

The way the local government worked, the office of mayor rotated annually among the elected members of the township committee. In 2004, it was Chaudry’s turn. As the US’s first Pakistani-American mayor, he made a triumphant visit to his homeland, where he met with the foreign minister, and gave interviews in which he hinted that he had ambitions for higher office. But local critics found him arrogant and high-handed. The next time he was up for election, he held on to his committee seat by just 11 votes.

The local Republican party was also in the midst of a schism, and Chaudry and his allies were ultimately driven out by a more conservative faction, which ran on the slogan: “It’s Time To Take Your Town Back.” The bad blood spilled over into the mosque dispute. The most damning evidence produced by the Islamic Society in the course of its lawsuit came from the correspondence of the town’s elected officials, many of whom had formerly served and clashed with Chaudry. They expressed their hostility in raw, racially offensive terms.

A town committee member named John Malay compared Chaudry to a stereotypically shifty native character in the 1930s film The Lives of a Bengal Lancer. “We [finally] ousted him, whereupon he went to Mecca, got a funny hat and declared himself the imam of a new mosque here in town,” Malay wrote. “Religion trumps even politics as a refuge for scoundrels, I guess.”

Other emails contained jokes about Muslims, pigs and Barack Obama. “Man child,” John Carpenter, another committee member, wrote of Obama. “The product of fools, raised by idiots and coddled by affirmative action. Behold the beast.” The emails revealed that Carpenter had even lobbied to prevent Chaudry from participating in a September 11 commemoration ceremony, alleging he was an extremist. “[Find] a real moderate Muslim,” he wrote. “There must be one. We shouldn’t look the other way on his views – we owe that to our dead residents. Let’s make it happen without that fool.” When the correspondence came out in court filings, Carpenter offered no apologies. “You should not confuse contempt with bigotry,” he told a newspaper. “I’m allowed to not like the guy.”

“He’s just a funny guy with this identity thing,” Carpenter told me when we met for coffee at a diner over the summer. “He was known as, quote, ‘Mr Muslim’.”

Carpenter, a tall, balding salesman, had served on the town committee for more than a decade, and was running for re-election. He was outraged that his unguarded words had been used to portray him – and the entire township – as racist. “When government tries to see into someone’s heart, that’s when we fall into totalitarianism,” he told me.

He advanced a conspiratorial theory, which I heard from other mosque opponents, that Chaudry had been “engineering failure” all along, so that he could sue and win millions in damages, as other mosques had done. He said he believed that Chaudry and the Obama administration had been conspiring. A Justice Department official involved in the investigation of the township, he noted, served with Chaudry on the board of a local university’s Center on Religion, Culture and Conflict. (Chaudry says they never discussed the case.)

“I find it ironic that he served on this council for religious conflict, and what he really was trying to do here – and I don’t think he succeeded in the end, because people see through it – is create a religious conflict,” Carpenter said. “I don’t think what happened is fair to the people of the town, and I think it’s important for other people around the country to know what’s coming their way.”

Carpenter said he had been hopeful that Trump’s election would bring “a little sanity to the Department of Justice”, and a reversal of its stance on the mosque case, but so far, he had been disappointed. He knew the president was spending his summer vacation at his private club in Bedminster, though, just a quick drive away from Basking Ridge. “He’s there for three weeks,” joked Carpenter, an avid cyclist. “Maybe I could sneak in, ride my bike up the back road: I need to speak to the president!”

All year long, as I kept returning to see Chaudry, Donald Trump loomed over our conversation. One Saturday morning in September, on my way to meet Chaudry at a Lutheran Church’s symposium on “Race, Hatred and Bigotry”, I looked up in the sky and saw the presidential helicopter heading toward Bedminster. Trump’s embrace of the worst in politics – fanning terrorism hysteria, retweeting racist memes, refusing to condemn the white nationalist demonstrators in Charlottesville – had real consequences on the ground. “People are emboldened to come out and say things that they never felt they could say before,” Chaudry told the symposium. “They have a licence, because the person in the highest office of the country is engaging in that kind of language.”At one point, the room suddenly filled with a disconcerting roar from low-flying military jets.

Chaudry introduced a pair of high school girls, one of whom was wearing hijab, who eloquently described their experiences with bullying confrontations on the school bus and social media platforms. “I would say to my non-Muslim friends: this is the Muslim community,” Chaudry said when they finished their presentation.

As the controversy over the mosque moved toward a settlement, the town committee held a series of heated public hearings. Many members of the Islamic Society attended, to show a human face to their neighbours. They always took care to present themselves as model citizens: upscale professionals, and the parents of striving children.

“We are not some strange boogeyman that came out of nowhere,” Yasmine Khalil told me. She was a doctor and a vocal mosque supporter, who had moved to the township from Manhattan a few years before. Khalil said she had been dismayed to see the ugliness infiltrate even a private Facebook group for local mothers, where she had got into commenting wars about Islam. “When I wasn’t just quiet and silent and in the background,” she said, “they took it upon themselves to kick me out.”

At one public meeting, a white-haired man – one of the crustier opposing voices – tripped and fell, and Khalil rushed across the room, thinking he might need medical assistance. He was fine, and the meeting went on. Khalil gave a speech, introducing herself as a mother. “We are your friends, we are your neighbours – I could be your doctor,” Khalil said. “I want my kids to feel like they’re welcomed. I want my kids to feel proud of the people that we have chosen to surround them with.”

The old man she had just rushed to help piped up: “Move to an appropriate place!”

Chaudry said non-Muslims in Basking Ridge would often pull him aside, to quietly confide that they were ashamed about what was happening to the town. He hoped that, at some point, the forces of conciliation would make themselves heard. Instead, the tenor of the debate only grew more hysterical. It reached its climax when a particularly vociferous mosque opponent named Nick Xu, a Chinese-American volunteer for Trump’s campaign, gave a speech claiming that the Islamic Society’s lawsuit was part of a “systematic plot” to wage war through the courts. “If you google ‘Islamic Lawfare’,” he said, “you’re going to see dozens, dozens of these kind of lawsuits.” In response to Xu, a man named James Rickey – a member of one of the town’s old Scots-Irish families – came to his feet, full of righteous contempt. “The tone that has been used here tonight is disgraceful,” Rickey said. “We’re all human beings. We should respect each other.”

With that, and without debate, the town committee grimly voted to approve the settlement, agreeing to reverse the planning board’s rejection while paying the Islamic Society $3.5m. John Carpenter was the lone dissenter. The townspeople again raised a loud clamour. “We understand your frustration,” the mayor told them. “But this is what we are required to do by federal law.”

A few weeks later, the Islamic Society celebrated the end of the holy month of Ramadan beneath a white tent set up next to a practice green at the Basking Ridge Country Club. Chaudry addressed the service while standing next to a poster-sized rendering of the mosque. “As many of you know,” he said, “we now have – alhamdulillah, alhamdulillah, alhamdulillah – a settlement with the township, which calls for us to submit a revised plan, and I am honoured to tell you that at 4.49pm yesterday I received from our engineers the plan that we intend to submit tomorrow, inshallah. Many people thought this was impossible. As Nelson Mandela said once, things seem impossible until they are done.”

For the holiday, Chaudry had secured the services of a guest imam who spoke of the “constant shockwave” that Trump’s election had sent through the Muslim community in America. When the prayers were finished, Chaudry stood at the front of the tent and accepted congratulations from members of his congregation. “People said, why are we doing this here, where people don’t like us?” he told one. “I say, where can you go where people like you?”

It is not yet clear what the Trump presidency will mean for the Justice Department’s policy on mosque disputes. Eric Rassbach, an attorney with the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, an anti-discrimination advocacy group, told me that so far the department “seems to be staying the course”. Still, ideological shifts take time to assert themselves within government bureaucracies, and Tom Perez said there is “every reason to be concerned” about the Justice Department’s direction. “Donald Trump certainly adds gas to the fire,” he said. “That will bring additional pressure to bear on the DOJ to do the wrong thing.”

Chaudry no longer considered himself a Republican, for obvious reasons, but he was still guarded in his criticism of Trump. All summer, while the president vacationed nearby, a few self-proclaimed members of the resistance would protest on a street corner in Bedminster. Chaudry never participated. Instead, he organised interfaith prayer services, and tried to be a moderating force. When an alleged Islamic State supporter from New Jersey killed eight people with a truck on a Manhattan bike path in October, Chaudry hastened to arrange a reassuring visit of police officials to a mosque near the suspect’s home, which was receiving death threats. Meanwhile, every time Trump tweeted something horrible about Muslims, Chaudry would wearily draw up a public statement. “With him, you can never tell what he’s going to say,” he said.

Under the terms of the Islamic Society’s settlement, the mosque was granted a rehearing before the planning board in August, at which “no commentary regarding Islam or Muslims” was to be considered. The procedure was a mere formality, and the mosque was approved. Lori Caratzola, who recently moved out of Basking Ridge, was not present for the vote. She did not respond to interview requests; neither did the Thomas More Law Center, the rightwing group that came to her aid in the Islamic Society’s lawsuit. With the federal case concluded, the issue of the subpoenas to private citizens is now moot. But the Thomas More Law Center has continued to file lawsuits on the behalf of other mosque opponents, including neighbour Loretta Quick, claiming that their elected representatives had “colluded with ISBR’s ‘Civilization Jihad’”. Another lawsuit, brought by a former member of the planning board, is challenging the mosque’s approval on procedural grounds.

“It’s far from over,” Zubulake told me. “We’re going to keep fighting it to the bitter end.”

While continuing to fight on the legal front, Chaudry is now raising funds – much of the settlement went to pay his lawyers, who are in turn donating the money to charity – while also going through the permitting process. He hopes to demolish the house soon, so he can hold a groundbreaking ceremony some time in 2018. One person who won’t be attending is the current town mayor, John Carpenter. He promptly appointed Nick Xu – the “Islamic lawfare” guy – to a pair of township boards.

Chaudry hopes, though, that constructing the mosque will pave the way for reconciliation with those opponents who are willing to listen. “I am a firm believer – perhaps I am more of an optimist than many people – but I feel that in human nature, when something has been done, people are more willing to accept it,” Chaudry said. “They will find that their fears were baseless.” He has a strong – religious – faith in the notion that differences among people are best overcome through cultural interchange. “Mosques are places where you build those bridges,” he said.

A recent Cato Institute survey found that 47% of all Republicans – and a quarter of Americans overall – would support a ban on building new mosques in their communities. Yet Islamophobia, like all prejudices, is rooted in ignorance, and Chaudry felt that if people could just see the inside of a mosque, they would lose their apprehension. “We want to dispel some of these misperceptions that exist,” he said.

In addition to his many other activities, Chaudry often teaches about Islam, lecturing at venues ranging from universities to the New Jersey state police academy. Last autumn, he offered a continuing education course to some senior citizens, and he invited me to a culminating event, a tour of a large mosque in the town of South Brunswick. The retirees shuffled across the carpeted floor, awkward and shoeless, as the midday prayer began. The imam, Hamad Ahmad Chebli, welcomed what he called “60 messengers”.

After the service, in an adjoining room, Chaudry and the imam took questions. Why were the women and men separated for prayers? Does the Qur’an prohibit women from driving? What’s the deal with sharia, and is it practiced in America? They answered each query patiently, providing some basic theology with a leavening dash of humour. A warm feeling of fellowship inflated like a soap bubble.

“I live nearby, and I’ve driven by this Islamic Society any number of times,” said one woman. “And I always wondered, what’s going on in there?”

“Making Islamic bombs!” Chebli interjected, eliciting a big laugh.

“What we’re doing,” she went on, “is we’re dispelling the mystery.”

“There was a strong feeling in the mosque, a feeling of peace,” said an elderly Jewish man. “I was crying, because there was this beauty to all of it.”

“I think occasions like this really help us all to understand what Islam and being a Muslim is all about,” said another woman. “And my biggest concern right now is what is happening to this country with our current president.”

There was a loud groan of disapproval.

“I didn’t mean to bring politics into it … ”

“Then why are you?” shouted another audience member. The bubble was punctured.

“America does not belong to any president,” the imam said. “America does not belong to any religion. This is our country.” Chaudry sought to defuse the sudden tension. He said he looked forward to welcoming more groups to visit, and learn, in Liberty Corner.

“Inshallah,” he said, “when we have our own mosque.”

All photographs by Fred R Conrad