Homework is a fraught issue. Some people think it’s necessary to help kids learn; others think it’s a waste of time. And many parents are confused about how much they should get involved with their kids’ homework.

A new study of 27,000 parents in 29 countries, conducted by the Varkey Foundation, sheds some light on how parents handle homework around the world. In India, Vietnam, Turkey, and Colombia, parents are putting in serious hours—on average, 12 hours, 10.2 hours, and 8.7 hours per week, respectively. Meanwhile, Japanese parents put in a paltry 2.6 hours on homework per week and Finnish parents offer a meager 3.1. Overall, 25% of parents worldwide spend seven or more hours a week helping their children with schoolwork.

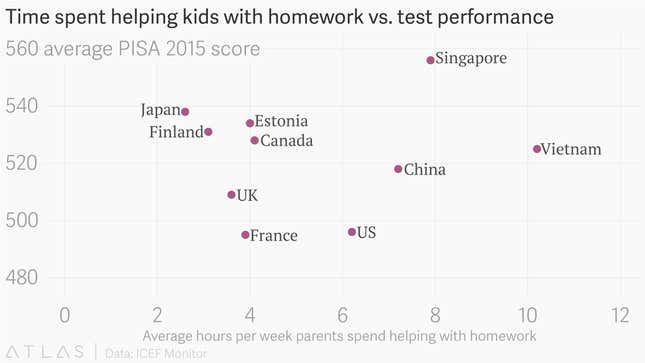

The thing is, spending more time with kids on homework doesn’t always seem to pay off—at least in terms of student scores on PISA, the critical-thinking test the OECD gives to 15-year olds every few years.

Here are the top performers in PISA:

With the exception of three countries—Singapore, China and Vietnam—the top-performing nations, in terms of test scores, are places where parents invest notably little time in their kids’ schoolwork. Here’s what that relationship looks like:

Of course, parents who spend less time on homework may well want to help. Nearly a third of parents worldwide feel that they spend too little time helping their children out of school. The most common reason they don’t help as much as they want to? Too busy, said just over half of parents.

Vikas Pota, CEO of the Varkey Foundation, said there are a few reasons high-performing education systems might have lower parent engagement in homework. Some of those countries might have parents who work long hours. In others, parents might not think it’s their role, with academics best left to a high-performing school system. ”It is also possible that the converse applies—that parents in emerging economies feel a greater sense of responsibility to work with schools to help their children improve their life chances,” he said.

In general, parents seem satisfied with the teachers in their schools, with Kenyans and Americans the happiest. And 78% of parents around the world rated their confidence in the quality of teaching at their schools as “good” or “very good.”

But just as parents spending more time on homework doesn’t necessarily correlate with test performance, there was little relationship between how highly parents rated their kids’ teachers and how well the country did on PISA. South Korea and Japan, two PISA superpowers, reported the lowest levels of confidence in the quality of their child’s teaching.

Those two countries were also the most pessimistic about whether their children were well-prepared for the future. Whereas 64% of parents globally say their child’s school is preparing them well for the world in 2030 and beyond, only 37% of South Korean parents and 48% of Japanese parents felt this way. Perhaps a bit of pessimism is what adds extra motivation for academic success.