Police in Indonesia believe they have uncovered a clandestine fake news operation designed to corrupt the political process and destabilise the government.

In a string of arrests across the archipelago in recent weeks, authorities have revealed the inner workings of a self-proclaimed cyber-jihadist network known as the Muslim Cyber Army (MCA).

The network is accused of spreading fake news and hate speech to inflame religious and ethnic schisms; fan paranoia around gay men and lesbians, alleged communists and Chinese people; and spread defamatory content to undermine the president.

Police say the network was orchestrated through a central Whatsapp group called the Family MCA.

One wing was tasked with stockpiling divisive content to disseminate, while a separate “sniper” team was employed to hack accounts and spread computer viruses on the electronic devices of their opponents.

The arrest of 14 individuals is the second such syndicate police have busted in the last year – deepening fears around Indonesia’s vulnerability to the pernicious spread of fake news.

False accounts and lies

In the world’s largest Muslim-majority nation, among the top five biggest users of Facebook and Twitter globally, some say it is unsurprising that rising religiosity and racial division is playing out viciously online.

It is in this environment that the Muslim Cyber Army was born and has since thrived, in a digital ecosystem flush with fake accounts, lies and bots, or automated accounts.

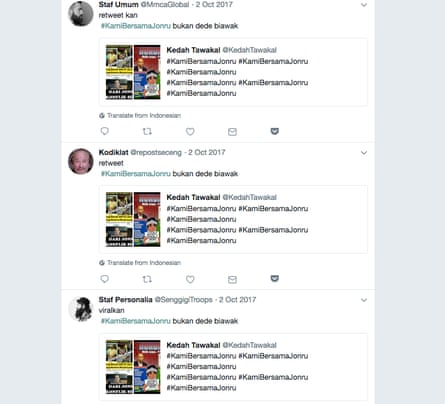

A Guardian investigation conducted over several months uncovered one coordinated cluster of the Muslim Cyber Army on Twitter.

The investigation identified:

- A Russian-doll-like system of more than 100 bots or semi-automated accounts.

- Links between the cyber army and opposition parties, as well as the military.

- Details of 103 cases of brutal “bounty hunting” incited by the “cyber-jihadists”.

The network identified by the Guardian was created for the sole purpose of tweeting inflammatory content and messages designed to amplify social and religious division, and push a hardline Islamist and anti-government line.

Tell-tale signs of a bot

The messaging was cleverly designed to appeal to broad Islamic sympathies.

Posts about the persecution of Muslims in Myanmar and Palestine, for example, were mixed in with domestically inspired vitriol, hatred for the Chinese minority, or support for hardline Indonesian figures and their protests.

The network, which functioned between July and November 2017, had all the tell-tale signs of being a network of bots and semi-automated accounts.

Posts were often identical in nature, with the same text, meme or hashtag repeated dozens of times. The accounts would sometimes tweet up to 30 times a day. All accounts were opaque, with no name or location, and followed identifiable patterns.

One group of 30 accounts, for example, featured striking profile photos of bearded, Viking-esque men, with the names of different Indonesian military bases or agencies, or government posts. Another set featured accounts with pictures of pigs.

The discovery illuminates how different interest groups operated within the MCA network for nefarious political ends. It also highlights how easy it is to game social media networks, especially Twitter.

With an army of bots, semi-automated and fake accounts, it is relatively simple to sway public perception, propel a hashtag into a trending list, or engineer an online poll.

In the lead-up to what is expected to be a heated 2019 presidential election – a likely replay of the bitter 2014 contest – the MCA has regularly generated questionable surveys. The polls often feature a picture of the two expected candidates, current president Joko Widodo, and his rival, former army general Prabowo Subianto.

Under pictures of the two men, users are asked to retweet for Prabowo or “like” for Widodo.

The results, retweeted by thousands of seemingly fake accounts and bots, invariably sway in the former general’s favour.

Viciously targeted

Last year there was 103 cases of so-called bounty hunting orchestrated by the Muslim Cyber Army, which circulated lists of people to attack – including their names, addresses, and identities of family members.

People deemed to have criticised Islam on social media accounts were viciously targeted, intimidated, beaten, and forced to record video apologies. In some cases these activities had explicit approval from the military, with officers present.

Analysts believe the MCA is a vast umbrella network utilised by various interested parties, united by its intolerant views and vocal mission to topple the president.

Damar Juniarto, from SAFEnet, the Southeast Asia Freedom of Expression Network, has been closely studying the Muslim Cyber Army.

“I found there are four clusters of the MCA,” he said. “Each cluster has its own agenda but they are coordinated in groups, with buzzers and also bot machines.”

“Buzzers” refers to accounts with large followings, in some cases more than 100,000, which are used to amplify messages from accounts with less traction.

Junianto’s clusters also reveal some interesting bedfellows: links to opposition parties, the military, and an organisation of increasingly influential Islamists.

The Twitter battlefield

Police have so far been tight-lipped about who is behind the network, but it is understood they are aware of at least one politically influential financier.

Digital strategists describe the recent onslaught of bots and cyber armies such as the MCA as akin to psychological warfare playing out “in the dark ages of the internet”.

Shafiq Pontoh, from the data consultancy firm Provetic, said Twitter in particular “has become a huge, bloody battlefield”.

“The first victim in the polluted ecosystem was the governor election, Ahok,” said Pontoh, referring to former Jakarta governor, Basuki ‘Ahok’ Tjahaja Purnama, who last year was jailed on controversial blasphemy charges.

“It was all because of fake news, bots, black campaigns, prejudice and racism.”

Clusters of bots in the Indonesia Twittersphere appear and disappear quickly, seemingly employed for short-term political gain. One cluster identified by the Guardian, which was used to pump out anti-Ahok material last year, stopped tweeting two days after the governor election and has been quiet since.

Savic Ali, online director at Indonesia’s largest Islamic group, Nahdlatul Ulama, suggested the Muslim Cyber Army is not really about the true values of Islam.

“This is the political imagination,” he said. “It’s about power.”

With concerns over rising intolerance and intense jockeying around the 2019 election already underway, few doubt Indonesia’s social networks will be increasingly gamed and weaponised.

Even after the recent arrests, Junianto believes it is just a matter of time before new manifestations appear.

“This is only the beginning,” he said. “They are getting equipped for 2019.”