Every year, feminists take this day to point out that despite women entering the labor market in droves over the last 50 years, we're still paid less than men for the work we do—79 percent of what men with the same work schedules make, with smaller percentages for women of color. And without fail, wage gap truthers use this day to argue that the gender wage gap is a myth. The raw gap isn't worth talking about, their story goes, because it can be narrowed when a variety of factors are taken into consideration, like education or age. Even more importantly for this cohort, the real cause of any gap is not unfair pay or even bias against working women, but personal choices. If women wanted to enter more lucrative fields or stay away from the temptation to be home with their children, then of course they would earn the same as men.

There is some truth to the counterpoints made against the gender wage gap, but none of them fully explain the disparity. The gap does indeed get narrower than 79 percent when economists take into account education, experience, race, industry, and occupation. If women and men with similar characteristics are compared, women make just about 90 percent of what men make. And women do stay home with young children at higher rates than men.

So if women want to earn equally, then it should stand to reason that they should simply get more education, add experience to their resumes, choose high-paying industries and jobs and stick with their careers.

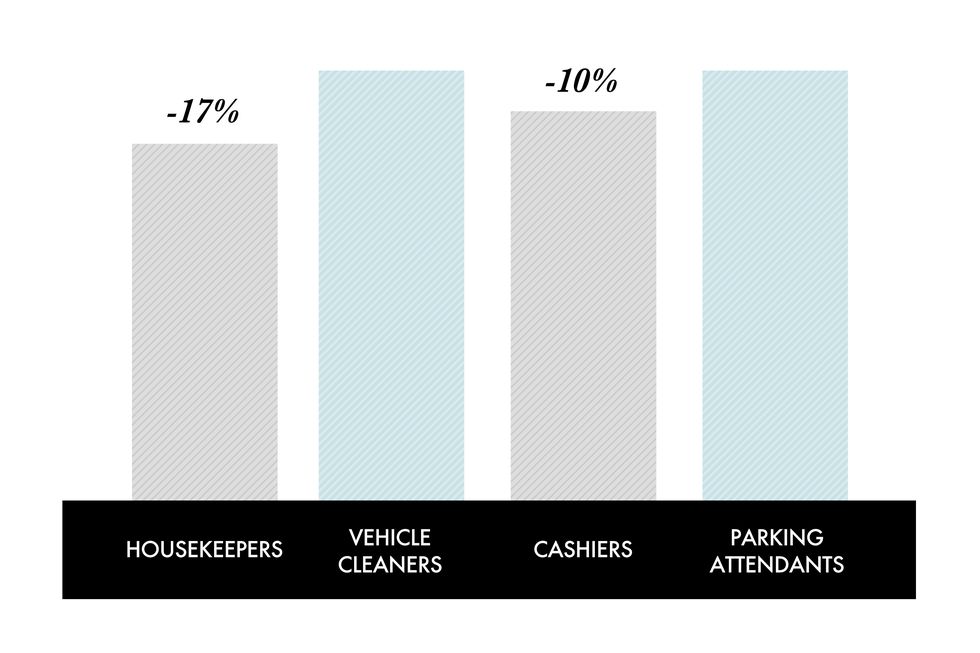

First let's take the idea that women chose lower-paying work. It's sad and true that median pay in female-dominated occupations (where women hold more than half the jobs) is 17 percent lower than those where men hold most of them. But women make less than men in every industry, even for work that's remarkably similar. Low-wage jobs dominated by women pay just three-quarters of what low-wage jobs held by men pay. For example, housekeepers, who are mostly women, make 17 percent less than people who clean vehicles and equipment, mostly men. Cashiers—women—make 10 percent less than parking lot attendants—men. And it's worse on the other end of the spectrum: High-paid female-dominated jobs pay just about two-thirds of what male-dominated jobs pay.

If women were to try to crowd themselves into the top jobs that are now monopolized by men, they wouldn't end up closing the wage gap. A comprehensive study looking at half a century of Census data found that when the share of women in a particular occupation increases, the pay drops. When women took over working in parks and camps, wages fell 57 percentage points, 34 points in designing, 21 points in housekeeping, and 18 points in biology. By contrast, computer programming used to be done mostly by women, but when men took over, prestige rose alongside pay. Employers simply value work less when it's done by women.

This holds true even when you zoom in to look at particular jobs. In virtually all of the hundreds of job categories tracked by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, women earn less than men at the median. To get even more specific, Glassdoor recently took crowd-sourced pay information and compared women and men with the same characteristics in the same exact jobs at the same companies. It found that women still make 5.4 percent less.

Education won't make up the difference either. Women are now getting Bachelor's degrees at the same rate as men, yet the gender wage gap hasn't significantly closed over the last decade. In fact, a study found that young, childless women graduating from the same colleges with the same majors and grades as their male peers—who should, by all rights, be primed for equal pay—still made less in their first jobs. Women make less than men, on average, at every educational level.

There are other factors that make it easy to blame women's choices. Differing experience levels can account for about 15 percent of the overall gender wage gap—meaning that women are spending less time in their careers than men, so they're not accumulating the promotions that would increase their earnings. The wage gap gets widest right as women enter their prime childbearing years.

But when you look at the reason behind this disparity in experience, it seems less a matter of choice than necessity. Women are still expected to take on the notorious second shift after they get home from work—not just raise the children, but care for aging parents, clean the house, and cook dinner, too. Many of them cut back or quit their jobs to take on that substantial care work, far more frequently than men do. Without affordable child care and more reasonable work hours, someone is going to have to pick up the labor that so frequently conflicts with paid work. That someone is still almost always a woman.

Recently, two highly respected economists updated their 2001 analysis to take everything into account as many of these variables as possible, and they still wound up with 38 percent of the gap unexplained—something that has been mirrored in other studies. It's impossible to say for sure that the unexplained forces driving men and women's salaries apart are due to discrimination or sexism. But it's not hard to imagine that's at least partly true. Studies have found that women's abilities are consistently devalued, even when they're doing the exact same things as men.

I wish that the gender wage gap was a figment of feminists' imagination. But as women are reminded not just on Equal Pay Day, but every time they get a paycheck, it's very real, and at the moment it doesn't appear to be going anywhere.