“Maybe Basel will believe in black women, ’cos they’re going to see a lot of ’em,” says Theaster Gates with a laugh. He is standing in the middle of a room in the Kunstmuseum Basel, where he is preparing an exhibition on the theme of the Black Madonna. Amid the packing materials and exhibits waiting to be hung stands a roughly life-sized sculpture of a seated Virgin Mary. She holds an orb in one hand. On her lap sits baby Jesus, also holding an orb. Her features are eroded as if she has been cast from a weathered medieval statue. And she is very black – made of a shiny, plasticky-looking material that turns out to be tar. Gates uses tar a lot in his work; his father was a roofer and bequeathed his son his tar kettle. “I feel like this is the Mary of my youth, ’cos it’s in tar,” says Gates. He leans in and sniffs her head. “Oh yeah, I know her.”

He explains that this tar Mary was not based on a medieval statue but a plastic keyring, just a couple of inches high, that a friend gave him as a good luck charm. “The keychain was already old, so the limbs had been busted off. She was probably carried in someone’s purse or their pocket with their keys, and then the cares of this world tore her apart.”

It is often hard to get a sense of scale with Gates’s work. At college, he studied urban planning and ceramics, and his work covers all points in between. He made his name a decade ago with an exhibition of pottery supposedly crafted by a Japanese master, “Shoji Yamaguchi”, who came to Mississippi and married a black civil rights activist. It was an elaborate fiction, complete with a mixed-race actor impersonating the potter’s son, but it got the art world’s attention. “White people love Japanese people,” he later explained.

At the other end of the scale, there’s his Rebuild Foundation, which has spent the last six years buying up condemned buildings (including a neoclassical 1920s bank building) in the infamously deprived, predominantly African American South Side district of his native Chicago. With the blessing of the city’s mayor, Rahm Emanuel, Gates has refurbished these buildings and repurposed them as community facilities: workshops for artists, apartments, a library, a black cinema.

In between, Gates has made art out of everyday materials, often salvaged from his buildings. He has become a collector and custodian of archives, including the image libraries of the influential African American magazines Ebony and Jet, and the record collection of Chicago house DJ Frankie Knuckles, who died in 2014. He lectures to town planners and is a professor at the University of Chicago. He also makes wild spiritual music with his band, the Black Monks of Mississippi. You never know what he’s going to do next – and you never have to wait very long to find out.

“My hope is that people would start to see some through-lines between my works of art,” he says. The Rebuild projects, for example, were not only about community and regeneration. “They were more about one’s ability to understand space and power and politics, and then really be a player, an instigator, in one’s own environment. So even though I was a black man in a black neighbourhood, talking about black power, what I was trying to demonstrate is that an artist who reads the dynamics of a situation can change the situation.”

One obvious through-line in Gates’s work is his consciousness of African American identity and experience. Another, which emerges in his work in Basel, is spirituality. “Over the last several years, the work has not shied away from subjects of faith, of what I call the immaterial world,” he says.

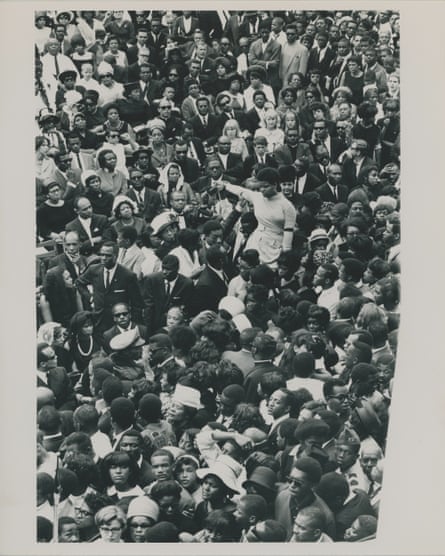

Basel is an apt location. The city is a centre of the art world (or, at least, the art market) thanks to its annual Art Basel fair, and it is virtually the geographical heart of Europe. And it is not, it has to be said, a place where you see many people of colour – either on the streets or on the walls of its galleries. Kunstmuseum Basel’s permanent collection features a wealth of European representations of the Virgin Mary (who was, let’s not forget, Middle Eastern). One of these, by 16th-century Dutch painter Maerten van Heemskerck, Gates is incorporating into his own exhibition. In the painting, Mary has smooth, rosy-white skin and blond hair. She looks quizzically at the viewer, as if to ask, “Are you sure I look like the Virgin Mary?” Van Heemskerck’s Madonna will be juxtaposed with 13,000 images of 20th-century black women from Gates’s Ebony and Jet archives, including politicians, celebrities, unknown models and everyday people.

“When I close my eyes and think of God, I see my mom,” he says. “I don’t see a white Jesus, I don’t see an oblique figure. Maybe there’s something really powerful about these unsung heroes that deserves attention today, or at least deserves my attention.” As well as cultural history, this is Gates reflecting on, perhaps even atoning for, his gender. “The work I make is really heavy, quite a substantial kind of male art – boy sculpture.” He flexes his muscles. But this is more a reflection on “the quiet and graceful power of women and of the mother”, he says. “Maybe, in this moment of the complexities of #MeToo, the retaking of power that women are asserting and articulating, that this male world, as we’ve known it, is over, that this Caucasian world we’ve known is over.”

So the exhibition is “also a bit of a redemptive moment,” he says. There are other facets to the show. Gates connects Europe’s tradition of Black Madonna icons to Detroit’s Shrine of the Black Madonna, a black liberation theology group established by Bishop Albert Cleage in the 1960s, which put African American political self-determination into a context of religious faith. It was a big influence on him. Last Sunday, he visited Switzerland’s Black Madonna of Einsiedeln, he tells me. “It was amazing to see the power of this crazy, powerful set of symbols all around. I was like, the Catholic church has this figured out! That people need things, in order to get from themselves to the thing to beyond the thing.”

Gates directs me to another piece he is installing: on the walls around his tar Madonna runs a continuous bookshelf that will contain 2,500 volumes, identically bound in black, with gold lettering. The books are another of his salvage missions: they were acquired from bookshops gone out of business and closed-down libraries, and are on African American subjects. He has arranged them so their titles can be read as a continuous poem, an “index to black experience”, as he puts it. Or as a prayer: When We March; Come Out Smoking; With Cloaks of Invisibility; Giants With Wonder; Spooks by Doors; Martyrs When Necessary, and so forth. “If people have a moment to read my prayer, it means they’re also praying,” he says.

Editions of this prayer/poem will be published throughout the exhibition in the room next door, which contains a heavy, 1960s Heidelberg printing press. Gates has borrowed it from the Basel Paper Mill museum, just up the road. “I almost feel like one part of the project is about me being a kind of new jack propagandist,” he says. “I’m Black Madonna Press, and my goal is the redissemination of the black image.”

This is another of those through-lines that connects Gates’s work. Much of it concerns history; things that might be lost or forgotten – saving them, preserving them, repurposing, reinserting them into cultural narratives, changing the situation. “One way I think about power is the ability to resurrect things that have been sleeping for a long time,” he agrees. It could be a condemned building or shop of discarded books or a 1960s image of an African American model, her hair straightened into a dynamic bob. Or it might be Knuckles’ record collection, which came to Gates simply because of his reputation for collecting things and liking house music. Rather than buying the records, Gates suggested Knuckles license them to him for 10 years. He invites DJs to come to his bank building and spin them and make mixtapes out of them. “It’s not about acquisition. The goal is to have these things keep circulating.”

Spreading the word, resurrecting the dead, writing prayers, chanting with his Black Monks, positing his mother as the Virgin Mary (and therefore himself as Jesus) – the connections between art and religion are not lost on Gates, and there is the implication he’s positing himself as a spiritual leader, but he would rather frame it as an ongoing process of enquiry.

Gates doesn’t go to church any more, but the church is always in him, he says. As a teenager, he was director of his local church youth choir. He once questioned whether to become an artist or a priest, a preacher or a scholar, a student of religion or of art. To some extent, they’ve all merged, Gates says. “Using the term ‘art’ gives me more latitude.”

He develops the thought. “I’m really trying to find my place in a world of forms material and immaterial,” he says. “Even though I may have some questions about the form of God or the form that the immaterial world takes, I have no doubt about the truth of its presence. Eighty per cent of my practice is about reaching those things out of an immaterial world and trying to manifest them.”