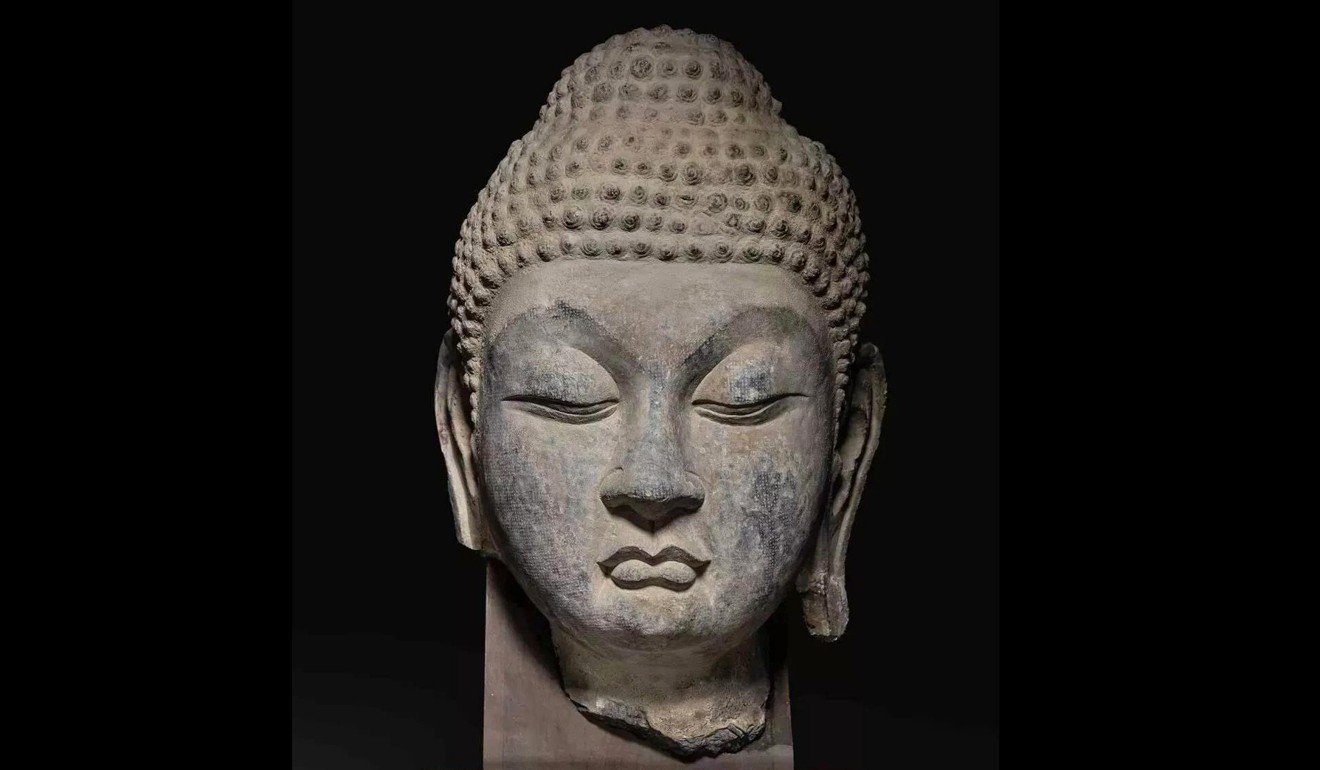

Buddha statue pulled from Sotheby’s auction on suspicion it may be from China Unesco site

A Buddha head from the Tang dynasty may have originated from a world heritage monument site

An intricately carved limestone Buddha head was removed from a Sotheby’s auction in New York this week, after evidence emerged that it may have originated from a Unesco heritage site in China.

Investigations are under way to determine if the sculpture is indeed one of the 100,000 statues from the ancient Buddhist Longmen Caves, a kilometre-long system of grottoes carved in limestone cliffs in central China’s Henan province

The item was pulled from sale ahead of the auction on September 12, but not before it was included in the list of Chinese artefacts published in the catalogue.

“Our attention was drawn to an image of a sculpture, very similar to the present work, published by a Japanese photographer who documented the Longmen Caves in the 1920s and 1930s,” Sotheby’s said on Friday.

Items in the auction, all from a private collection, were valued between US$10,000 and US$2.5 million, according to the Sotheby’s website. Although the Buddha was removed from the catalogue, an online listing showed the Tang dynasty relic was valued at between US$2 million and US$3 million.

News of the removal of the Buddha head from the sale became a topic of social media discussion in China when the resemblance was noticed to an image captured by Japanese scholars Tokiwa Daijo and Sekino Tadashi in the 1920s, according to Chinese media reports.

China’s Ming tomb raiders sent to prison for theft of ancient relics

The removal of listed items from art auctions is not uncommon, and can occur for a variety of reasons. However, this case reflects a larger, ongoing conversation within China about the repatriation of a huge number of artworks and artefacts stolen or plundered from China by foreigners and foreign soldiers, especially in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Catherine Maudsley, a Hong Kong-based curator and art adviser, has observed the growing phenomenon over the years as collectors and institutions in China look to buy back artefacts which have left the country.

“When a nation gains confidence, strength, and influence, it’s natural that looking into patrimony and repatriation will occur,” she said.

Maudsley attributed this interest both to China’s economic and political strength, as well as to the vastly expanded digital access to collections of museums and galleries around the world.

“Globally we are now more aware of what pieces are in what museums. Anyone with a computer can do this kind of research,” she said, explaining that this had raised awareness about how many Chinese artefacts were housed outside China.

While most jurisdictions do not have requirements about the documentation needed for the sale of such items, a 1970 United Nations convention regarding cultural heritage has raised standards of scrutiny on their sale.

Buyers from museums and galleries now look for a paper trail of legal ownership that at least dates back to when the conventions were established, according to Steven Gallagher, associate professor in practice of law at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

“Christie's and Sotheby’s are keen to make sure they know where these things are from because, to get the best prices, they are going to need to provide this information,” he said, referring to the major global art auction houses.

“The problem is that often the provenance is faked.”

Finding a trail of ownership in such cases can be difficult, because of the movement of art through different jurisdictions. Gallagher says that, for this reason, cases of disputed ownership and stolen art are often settled in out of court negotiations.

US-China trade war takes a cultural turn after antiques and artworks are added to Trump’s tariffs list

An unofficial online listing of the recalled Buddha head indicates that it was sold by a New York City-based auction house in 1955.

It remains unclear whether the limestone Buddha head falls into the category of an illegally removed artefact but Sotheby’s, whose art institute offers training to those in the industry on art repatriation to China, is reviewing the case.

In April, China condemned the British auction of a rare 3,000-year-old bronze water vessel seized by a British soldier from an imperial palace in Beijing in the 19th century.

The vessel, referred to as a Tiger Ying for its tiger decorations, is believed to be one of only seven similar archaic vessels in existence. It was auctioned at the Canterbury Auction Galleries in southeast of England at £410,000 (US$540,000), more than twice its estimated value.