Researchers may have found the first signs of an exomoon

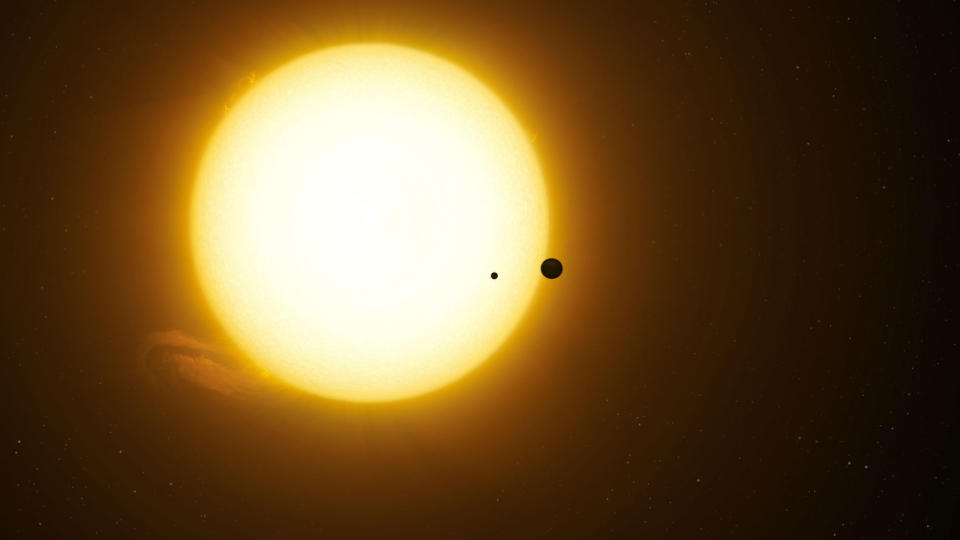

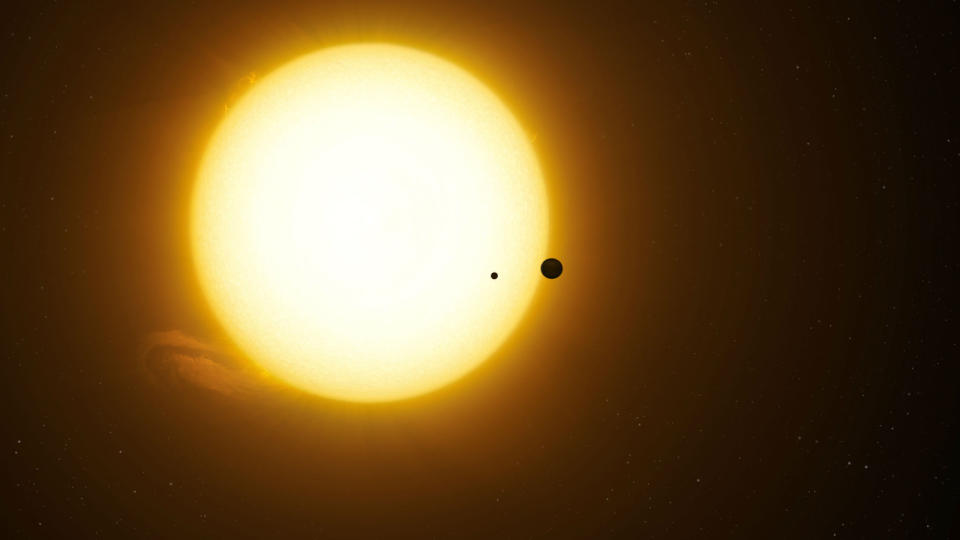

The Neptune-sized object is orbiting the star Kepler-1625.

Over the last couple of decades, we've spotted thousands of planets outside of our solar system -- Kepler alone has confirmed more than 2,600. But so far, we've haven't found any exomoons, despite the likelihood of them being prevalent in our galaxy. Because moons tend to be much smaller than their planet counterparts, they're harder to spot, which is probably why we have yet to find any. However, researchers at Columbia University have now found evidence of what might be an exomoon located thousands of light-years from Earth.

The scientists analyzed data from 284 exoplanets discovered by Kepler, looking for signs of an exomoon. And last year, they announced that they might have found one. More observations were needed before they could draw any conclusions, but the evidence scored them 40 hours of observation time with the Hubble telescope.

With the Hubble, they monitored the exoplanet Kepler-1625b as it passed between the star it orbits -- Kepler-1625 -- and Earth, and they looked at how the brightness of that star dimmed as the planet passed in front of it. They found two signs suggesting an exomoon could be in tow. First, after the planet passed by, the star's brightness dimmed a second time, though by a smaller amount, which suggested a smaller object, like a moon, was trailing the exoplanet. Secondly, the planet's transit time occurred earlier than expected, which could be caused by an orbiting moon pulling at the planet and causing it to wobble. Our moon does the same to Earth.

"A companion moon is the simplest and most natural explanation for the second dip in the light curve and the orbit-timing deviation," said Alex Teachey, one of the researchers on the project. "It was a shocking moment to see that light curve, my heart started beating a little faster and I just kept looking at that signature. But we knew our job was to keep a level head testing every conceivable way in which the data could be tricking us until we were left with no other explanation."

The scientists note in a paper published in Science Advances that the existence of the exomoon is still unconfirmed, and follow-up observations are needed. "If confirmed by follow-up Hubble observations, the finding could provide vital clues about the development of planetary systems and may cause experts to revisit theories of how moons form around planets," said study co-author David Kipping, an assistant professor of astronomy at Columbia University. An alternative explanation could be that a second planet is orbiting Kepler-1625 alongside Kepler-1625b. However, Kepler didn't find evidence of any additional planets in this system.

The potential exomoon is about the size of Neptune and the planet it orbits is several times larger than Jupiter. The large size of the possible exomoon is likely why it was first to be spotted, but the James Webb Space Telescope -- NASA's Hubble successor that's scheduled to launch in 2021 -- will be able to track down smaller objects. "We can expect to see really tiny moons with Webb," said Kipping.