Seven months ago, 18-year-old Bahara* was imprisoned for failing a test that she should never have had to undergo.

Bahara had run away from home to meet a man she had been in a relationship with. They had never met, but were in contact through calls and messages. That night, when they met for the first time, he raped her. But when she reported the rape to the police, instead of support, she was taken to hospital to undergo a virginity test – a practice that was banned in Afghanistan in 2016.

“I was on my period that day, too, and I pleaded for them not to send me. They wouldn’t listen,” Bahara says.

“I thought the doctors would at least take me to a private place for the test. But it was done in a room full of people – doctors, nurses, and even prying visitors and other patients who wanted a closer look at my naked body. At that moment, I would have preferred to die,” she says.

A female doctor performed the test using her two fingers, checking if the hymen was intact. After enduring the physical and emotional ordeal, Bahara was told she needed to undergo another test. “Because I was on my period they couldn’t gather accurate results,” she says.

Bahara is now an inmate at Mazar-i-Sharif high security prison in Balkh province. Many women have been imprisoned here for what are considered “moral crimes”, which include running away from home and having sex before marriage. Most will have had to undergo virginity tests and many women will spend months in jail because they failed them.

Women imprisoned for running away have usually fled dire circumstances, from domestic violence to forced sex work, and women categorised as “moral criminals” are jailed alongside convicted murderers.

Now campaigners hope that the passing of a public health policy to ban virginity testing in hospitals and clinics will bring significant change. The testing, which has been condemned as degrading and discriminatory, was officially banned in 2016, but that hasn’t stopped police taking women and girls for testing or stopped hospitals and clinics performing tests.

At Mazar-i-Sharif prison, in a small courtyard smelling heavily of cigarettes, women talk on phones, pace up and down, wash clothes and eat fruit. Inside, a female psychologist leads a group therapy session, organised by Marie Stopes International.

Following the announcement of the new policy, Marie Stopes, with funding from the Swedish government, will work with healthcare professionals in every Afghan province to ensure they know about the ban, and implement it.

The twice-weekly sessions at the prison are a chance for women to share their feelings about how they came to be in the prison, to build trust and discuss their hopes and fears for the future. The room is decorated with drawings that reflect their aspirations for life after jail.

But even though they will eventually leave the prison, the stigma of their “crime” will remain. Bahara longs to be released, but she is fearful of what awaits on the outside.

“I’m not sure I can rejoin society and go back to living a normal life. My being here has damaged my family’s reputation, and I truly fear my father might kill me once I’m out,” she says. “Even if a person is a criminal, they’re still a human. Human beings don’t deserve to go through what I went through.”

The fear of being accused of not being a virgin permeates society.

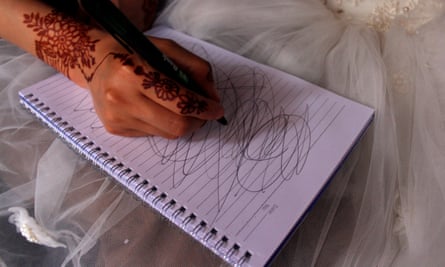

At a beauty parlour in Kabul, Hosnia is worried about her wedding night. Staring down at her shaking hands, decorated with intricate henna patterns in preparation for her wedding the next day, she says a female relative didn’t bleed on her wedding night, and was punished for it.

“Even if they’re virgins, some girls just don’t bleed after their first time. But here, it’s widely believed that if you don’t bleed, you’re not pure.”

Although Hosnia was a virgin, she was terrified that she might not bleed – a concern shared by many women in Afghanistan. In most cases, a bride who doesn’t bleed is “returned” to her father by her husband, divorced immediately, or in some cases even killed. “I’ve never talked about virginity with my fiancé before,” she says.

Before the national public health policy was passed, progress was slowly being made in parts of the capital to stop virginity testing and arrests for “moral crimes”. Colonel Bismillah Taban, police commander for District 9 in Kabul, banned police from sending women for testing, paving the way for further progress. Before he took up his post, he said, women who were seen by police in public places with other men were immediately suspected of having sexual intercourse, and sent for testing.

The Afghanistan Forensic Science Organisation, an NGO, says: “Hymen examination doesn’t only have a negative psychological impact on girls and women. It is a dangerous test, which in some cases causes physical pain, damage to the hymen, bleeding and infections.”

The organisation’s director, Mohammad Ashraf Bakhteyari, says that not only does virginity testing violate human rights, “bleeding is not a sign of a hymen’s existence or absence”. But this information is not widely known, as too few Afghan school students receive any kind of sex education.

Zahra Sepehr, director of the organisation Development and Support of Afghan Women and Children, says the school curriculum needs to change. “If sex education isn’t taught in an academic environment, our children will learn about it through porn or other unreliable sources,” she says. “Schools have to conduct meetings with parents and teachers to encourage discussion about adultery, sex education and hormone changes. These discussions will then raise enlightened, educated students who are aware of their bodies. This will also go a long way to discouraging boys from inflicting violence or unwanted attention on women.”

Back at Mazar-i-Sharif, Bahara is trying to remain positive. “I want to be hopeful and really wait for the day to see my family happy again and hug my mother, as I miss her a lot. In the future, I would love to continue my education and become a teacher to educate my students, especially girls, so they do not face what I experienced in my life.”

*Names have been changed to protect identities

Fariba Housaini is a member of Sahar Speaks, a programme providing training, mentoring and publishing opportunities for Afghan female journalists