Why Dora Maar is much more than Picasso’s Weeping Woman

Centre Pompidou

Centre PompidouThe Surrealist photographer is primarily known as the subject of Picasso’s paintings – but she deserves to be known as an artist in her own right, writes Cath Pound.

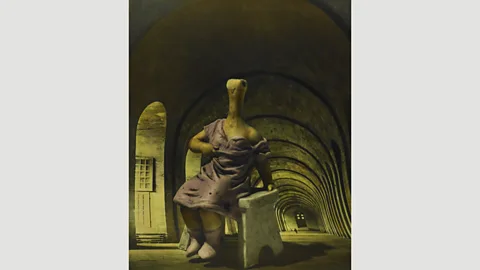

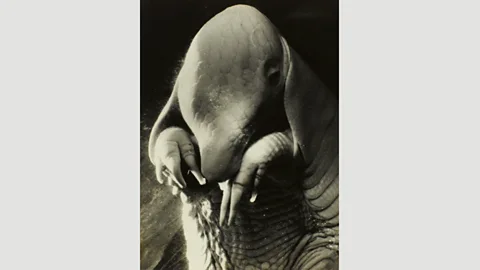

Dora Maar was one of the most important Surrealist photographers and the only artist to exhibit in all six of the group’s international exhibitions. Her photomontage 29, rue d’Astorg, in which a disturbing heavy-limbed figure sits in front of a distorted gallery, and Portrait d’Ubu, a curiously poignant portrayal of the lead character in Alfred Jarry’s play Ubu Roi as a baby armadillo, became icons of the movement.

More like this:

Yet today she is primarily known as Picasso’s Weeping Woman. Her tears, obsessively depicted in numerous canvases, seem to show a woman broken by the abusive relationship that contributed to a breakdown and her withdrawal from public life.

Although a consciously enigmatic woman who left little written evidence about her life or work, Maar deeply resented the image. “All (Picasso’s) portraits of me are lies. They’re Picassos. Not one is Dora Maar,” she told the US writer James Lord. In fact, Maar continued to create throughout her life, leaving a vast and highly varied body of work, much of which was only discovered upon her death.

Centre Pompidou

Centre PompidouThe first ever retrospective of her work has just opened at the Pompidou Centre in Paris, and will be travelling to London’s Tate Modern and the J Paul Getty Museum. Its curators hope to both restore her reputation as a photographer and reveal her virtually unknown works on canvas.

Born Henriette Théodora Markovitch in Paris, Maar spent much of her childhood and adolescence in Argentina because of her father’s work as an architect. On returning to Paris to study art she formed friendships with Jacqueline Lamba, who would become André Breton’s wife, and Henri Cartier-Bresson. The three studied under Cubist painter André Lhote but when it became evident that Lhote’s teaching methods didn’t suit her, Cartier-Bresson was one of several who advised her to focus on photography instead.

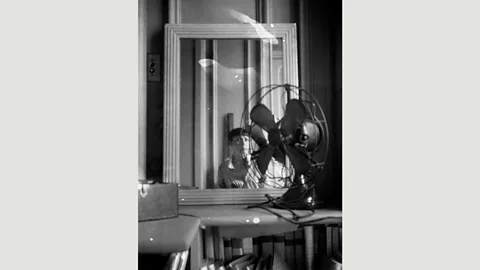

Inherently gifted and highly disciplined, Maar soon grasped the medium’s technical intricacies. In a striking self-portrait from 1930, she depicted herself reflected in a mirror, the oval of her grave face echoed by an electric fan.

Centre Pompidou

Centre PompidouBy 1930 she had shortened her name to Dora Maar and begun her career as a professional photographer. “She was part of something really new in advertising and fashion photography,” says the Pompidou’s curator Damarice Amao.

‘Left-wing ideology’

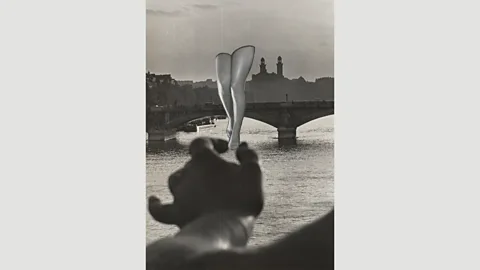

The fact that these genres were yet to be rigidly defined meant that she was free to let her imagination run riot. In her work for Le Figaro, she superimposed bikini-clad models onto the rippling water of a swimming pool – while in the more avant-garde Heim, she experimented with proto-Surrealist photomontages by placing images in mirrors held by severed mannequin hands.

Centre Pompidou

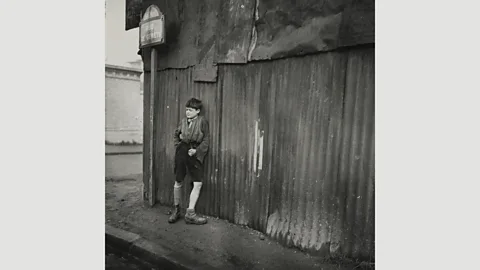

Centre PompidouAt the same time she was expressing her vehemently left-wing ideology via her street photography in Paris, Barcelona and London. In an untitled work from 1933, a child, his face stripped of all youthful exuberance, leans sullenly against a corrugated iron wall, a powerful reflection on the poverty which spread throughout Europe following the financial crisis of 1929.

Here too she explored what Breton referred to as the “bewildering strangeness” of the familiar, making curiously enigmatic images with shop window mannequins abandoned in niches of walls, or reflected in window panes.

“Both her street photography and her commercial work provided spaces wherein she would experiment and play and begin to think about Surrealism,” says Amanda Maddox, curator at the J Paul Getty Museum. “She was thinking about how these kinds of work interrelated and I think that separated her from a lot of other photographers.”

Centre Pompidou

Centre PompidouMaar was drawn to the Surrealists for their left-wing politics as well as their artistic ideology. She joined political meetings at the Café de la Place Blanche in Pigalle and added her signature to manifestos such as Contre-attaque (Counter Attack) which Breton had set up to protest the rise of fascism.

Her set included Man Ray and Brassaï, both of whom would photograph her – Man Ray as a sultry solarised beauty and Brassaï in more contemplative mode amongst her canvases at the height of World War Two. The poet Paul Éluard was also a close friend and she captured the delicate essence of his wife Nusch in some of her most dazzling portraits.

Centre Pompidou

Centre PompidouIt was Éluard who introduced Maar to Picasso at a press screening in January 1936 when she was working as a stills photographer on Jean Renoir’s film Le Crime de Monsieur Lange. They became lovers soon afterwards.

At the time Picasso was in a difficult situation both personally and professionally. His marriage to Olga Khokhlova had broken up following the pregnancy of his lover Marie-Thérèse Walter and he was lacking artistic inspiration.

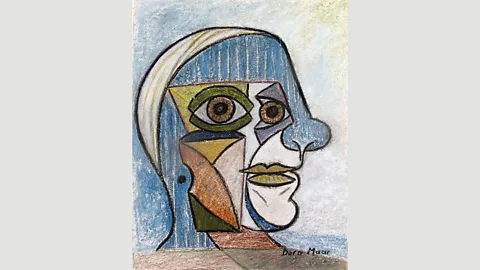

Courtesy Galerie Brame et Lorenceau

Courtesy Galerie Brame et Lorenceau“When he met Dora Maar it was like the starting of a new Picasso,” says Amao. Indeed, without Maar it is unlikely that he would have created what is considered one of the greatest works of 20th-Century art; certainly not in the form we know it.

Channelling anguish

Following the outbreak of civil war in Spain in 1936, both she and Éluard persuaded the previously apolitical artist to take an anti-fascist stance. When German and Italian forces decimated a rebellious Spanish town on Franco’s request the following year, the intense discussions he had with Maar prompted not only the creation but also the black and white photo-like format of Guernica.

The fact that Maar was also invited to document the different stages of Guernica’s creation is a testament to their close artistic relationship. But this did not prevent Picasso engaging in intense cruelty towards his lover. In what he allegedly described as one of his “choice memories” he even had Maar and Walter, from whom he had never separated, fight over his affection.

Despite the fraught nature of Maar’s relationship with Picasso, Maddox believes that through it she was “reinvigorated as a painter”. Early canvases show his unmistakable influence, but the trauma of the war years saw Maar’s talent come into her own.

Maar had to contend with her father’s return to Argentina, her mother’s unexpected death in 1942 and the exile of close friends such as Jacqueline Lamba. She channelled her anguish into a series of melancholic depictions of the banks of the Seine and still-lifes painted in grey and brown tones that echoed the dreary, unsettling nature of life under occupation.

Galerie Makassar-France, Paris

Galerie Makassar-France, ParisExhibitions at the Salon d’Automne and Galerie Jeanne Bucher won many accolades, including from her former tutor André Lhote, and solo and group shows followed. However, the following year the combined pressures of the war years and the gradual disintegration of her relationship with Picasso took its toll and she had a breakdown.

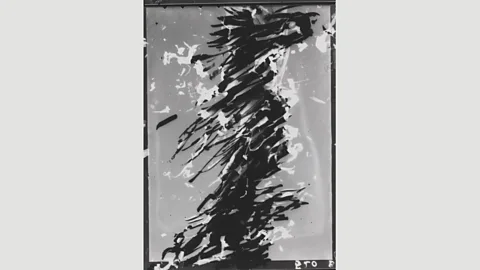

Maar gradually withdrew from the world, seeking refuge in religion and mysticism, but she never stopped creating. In the late 1940s and 50s she turned to portrait painting, that of Gertrude Stein’s partner Alice B Toklas being the most notable example. The 1960s saw sketches she made of stained glass windows during mass turned into abstract painting and in the 1980s she even returned to the darkroom to create a series of imaginative photograms (photographic images made without a camera).

Collection Centre Pompidou, Paris

Collection Centre Pompidou, ParisThe critical response to her oeuvre, which remains virtually unknown has yet to be seen but Maddox hopes people will appreciate that Maar “was producing work that was complicated and fascinating and merits re-examination”. Forget The Weeping Woman and look at what she created. Passionate. Daring. Innovative. Contemplative. That is Dora Maar.

Dora Maar is at the Pompidou Centre until 29 July; at Tate Modern from 20 November 2019 to 15 March 2020 and the J Paul Getty Museum from 21 April to 26 July 2020.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.