The New Populist Playbook

Matteo Salvini is not merely a Donald Trump facsimile—the Italian politician has been testing whether Facebook likes translate into votes, and is remaking his country along the way.

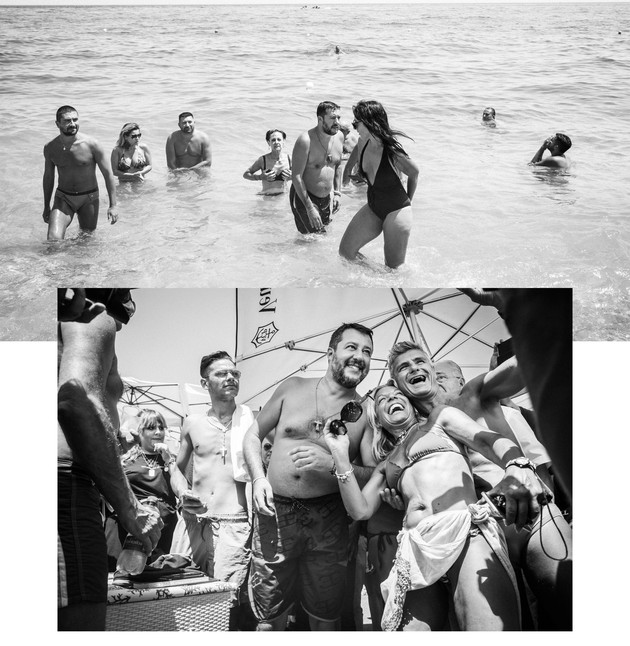

In May, Matteo Salvini, then the interior minister and deputy prime minister in Italy’s first populist government, stood in front of a Milan cathedral with other European far-right politicians, holding a rosary, and called for a defense of Christian Europe against its replacement by foreigners. In August, he campaigned and DJed—shirtless, cross around his neck, mojito in hand—at a beach club where female dancers in low-cut leopard-print bathing suits gyrated to the Italian national anthem. Throughout, his social-media accounts posted a steady stream of videos of cats, dogs, food, and immigrants behaving badly.

Salvini’s formula has been to combine tough “us versus them” talk on immigration and emotional, yet vague, defenses of national identity with an Italian-everyman relatability. “Buongiorno, amici!” is his standard form of address. “Hello, friends!” After each rally, Salvini poses for selfies, sometimes for hours. Every selfie a vote, is his strategy. His clever use of social media—his Facebook page has more overall engagement than President Donald Trump’s—has helped him build a cult of personality that’s painstakingly curated so as to make him seem unscripted. His popularity has allowed him to transcend his party, the right-wing League, and become the face of Italy, eclipsing the prime minister in the public imagination.

In 15 months as the junior member of the government, Salvini’s relentless campaigning—while interior minister—helped his party double its standing in opinion polls, clearly outpacing any other party, including his former coalition partner, the anti-establishment Five Star Movement. The League placed first in Italy in elections for the European Parliament in May, with 34 percent of the vote. All the while, Salvini has shrugged off unanswered questions about the League’s ties to Russia and whether he really wants Italy to stay in the euro.

The seemingly unstoppable momentum emboldened Salvini to put his popularity to the test. He withdrew his party’s support for the government, forcing a crisis in a bid for new elections that he hoped would make him prime minister of the first far-right government of a major European power. He didn’t get his wish this time. Instead, the Five Star Movement and the center-left Democratic Party—one representing the populist anti-establishment, the other the establishment—put aside their long-standing mutual animosity to form the strangest new government in recent Italian history, one with a sole purpose: to block Salvini.

Salvini may have miscalculated—out of hubris, perhaps—yet he is still at the forefront of Italian and European politics; he is the center of gravity, the man whom rivals fear most. The rise of this charismatic former talk-radio host, political chameleon, and turbocharged techno-populist is instructive, and marks a new and notable chapter of democracy in the age of social media. Salvini has swiftly and dramatically changed the culture in Italy, humanizing far-right rhetoric and making public discourse and the mood on the street rougher and more aggressive. He is not simply a Donald Trump facsimile in Europe, nor merely the archetype of an angry anti-immigrant nationalist in the Viktor Orbán mold. Salvini has been writing an entirely new playbook for 21st-century populism.

More than a Mediterranean hothouse, Italy has always been a political laboratory, a harbinger of things to come. Its revolutions have all been right-wing—from fascism to futurism to Silvio Berlusconi. Yet what has been unfolding with Salvini has implications beyond Italy, across Europe and for other democracies. More than any other politician in the world today, he has been testing the relationship between clicks and consensus—whether slow-moving institutions in Italy and Europe, to say nothing of rival political parties, can withstand the use of lightning-fast, reactive social media. Whereas Trump has used Twitter, both while campaigning and in office, to set the news agenda, Salvini goes a step further. He uses it to bring his supporters closer to him, making them feel as though he is one of them. While Trump’s rallies are where he seems to feel most at home, for Salvini it is also the moments after, when he spends hours, arm extended, taking selfies with his supporters. And though Trump’s social-media missives give off an air of haphazard responsiveness, Salvini’s are part of a well-honed machine that has given significant thought to experimenting with whether Facebook likes translate into votes.

In many ways, Salvini, whose supporters call him “Il Capitano,” or “the captain,” is a product of circumstance. Berlusconi, who stepped down as prime minister in 2011, paved the way. His Forza Italia was also a charismatic movement and stunted the growth of a non-personality-driven Italian right. It was Berlusconi’s private television networks that created a viewership that then became an electorate years before Trump did the same with The Apprentice. On his watch, Italy’s economy lost years—it has barely grown in two decades—and its electorate, already cynical, became even more disillusioned. Then came Trump, who emboldened nativist copycats worldwide. Salvini shares a siege mentality with Trump. He has championed a bill that legalizes shooting intruders in self-defense, and another that would allow chemical castration of rapists. What the southern border is to Trump, ports are to Salvini, and he has pledged to close them to what he calls an “invasion” of immigrants entering the country illegally.

In the process, he has started a battle over the soul of Italy: whether it’s a country of the big-hearted “do-gooders” Salvini disparages, or of tough border defenders. Salvini’s focus on migrants isn’t just about immigration. It’s a fluid frame that easily and quickly expands into vaguer and more emotional questions of national identity, race, and belonging. A savvy politician can fish for years in these deep waters. There’s something of the “return of the repressed” about Salvini. He is a product of Europe’s (and Italy’s) mishandling of the immigration crisis and the debt crisis. He has easy access to Italian sentiments of anger, powerlessness, economic instability—feelings that helped populists come to power in 2018, when the Five Star Movement, with its promises of a minimum basic income for low-earning Italians, placed first, the center-left Democratic Party second, and the League third.

Trump’s tweets cause international incidents; Salvini’s are a running ticker of the Italian subconscious. This allows him to be at once ubiquitous and totally opaque—and to keep everyone guessing about his motives and beliefs, ever present online but rarely clarifying his stance on major issues. The near-total control Salvini exercises over his party and its message makes it extremely difficult to pin him down. How far to the right is he, exactly? Would he moderate if he became prime minister? Would he push Italy closer to the Visegrád group of central and eastern European countries, or work with Brussels? Italy has seven NATO bases; where does he stand on NATO? What are his views on race? What about the euro? What does he believe in, exactly, beyond his own will to power?

I asked these questions in Italy for months, as Salvini rose and rose in the polls, and interviewed dozens of people. And for months, I was gaslit by Salvini advisers who dismissed my questions as typical of the “mainstream” media, or who told me Salvini didn’t intend to alter any existing treaties, but then wouldn’t go on the record because they didn’t have permission to talk. I was met with blank stares, and looked at as if I were crazy. What do you mean, “political evolution”? What do you mean, “believe in”? Some of the best minds in Italy told me they thought not even Salvini knew what he wanted or believed in, besides polls.

Many Italians see Salvini’s rise and his transformation of the League in terms of pure Machiavellian power politics. “There’s no ideology,” Maurizio Molinari, the editor in chief of La Stampa, an Italian daily, told me. Salvini would “even sell his mother” if it helped him get votes, Molinari said. Flavio Tosi, a former mayor of Verona from the League who had a falling-out with Salvini, told me Salvini believes in “whatever helps him electorally” at any given moment. “If tomorrow Italians wanted immigration, he’d want it, too,” Tosi said. Alessandro Trocino, who’s followed Salvini for two decades as a reporter for the Italian daily Corriere della Sera and written a history of the League, describes a Jekyll-and-Hyde quality to Salvini. At dinner, “he’s totally reasonable, he says sensible things, he’s never extreme. He’s very nice and is a great communicator,” Trocino told me. Then, at his rallies, he says “monstrous” things, like that Italian cities need a “mass cleansing” to rid them of immigrants.

Trocino, like most veteran Italian political journalists, shrugs this off as a naked power play. Salvini saw an opening on the right after the decline of Berlusconi and he claimed it, which meant tacking right on immigration and values issues. Trocino told me he still has a T-shirt Salvini gave him when he was leader of the Young Padanians, the League’s youth group, back when the party was called the Northern League and railed against Rome’s stealing its hard-earned tax revenue and sending it to what the party saw as the lazy bums of the violent, organized-crime-ridden south. It reads: Milan works, Rome steals, Naples shoots.

The League was founded in 1989 as the Northern League, a separatist party that mostly wanted more tax autonomy for Italy’s wealthy north. Its rhetoric tended toward the xenophobic even then, and had folkloristic elements—a veneration of the Po river and a belief in a fictional, vaguely Celtic-inspired homeland called Padania, which the party claimed it wanted to secede from Italy. The party’s color was green and its logo a wagon wheel whose spokes were leaves. When Salvini was elected party leader in December 2013, it was polling at 4 percent and in the throes of a scandal in which its co-founder and other officials were charged with absconding with €49 million, or $54 million, in public funds. (A court dropped the fraud charges, saying the statute of limitations had expired, but ruled that the party must still repay the funds.)

Salvini has transformed the League into a national party, replacing Rome with Brussels, the de facto seat of the European Union, as the enemy and subjugator. He now rails against the tyranny of the EU—in particular its failings on immigration and its irritating rules, including one requiring Italy to keep its budget deficits low. The party’s color has changed to blue and its logo is a knight on horseback wielding a sword, a kind of male Joan of Arc defending the nation. Under Salvini, the League has been courting, and winning over, voters in the Italian south, land of economic stagnation and high unemployment—the same southern regions from which his party once wanted to secede.

A model for the party’s transformation is France’s far-right National Rally, led by Marine Le Pen. Both parties have over the years absorbed working-class voters who used to vote Communist. But under Salvini, the League’s rise has been astronomic, whereas Le Pen has yet to hold national power, due in part to differences in the two countries’ electoral systems. A year ago Le Pen was Salvini’s mentor. Today he has become an exemplar for far-right politicians.

The League’s expansion has created some internal tensions. It governs the prosperous northern Lombardy and Veneto regions, which still want more tax autonomy, even as Salvini courts southern voters. But Salvini has done to the League what Trump has done to the Republican Party—the old guard may have different priorities, but they’ve been afraid to break with a leader who’s so powerful and so popular among the growing rank and file. (Or at least who was until his gamble pushed his party into opposition.)

Salvini’s takeover of the League marked a rare generational change within an Italian political party, but one he had been preparing for his whole life. Salvini was born in Milan in 1973 to a middle-class family. His father had an office job at a chemical factory and his mother was a German-language translator. He joined the then–Northern League’s youth wing as a teenager, while a student at one of Milan’s most prestigious public high schools. (His family wasn’t very politically active and supported a small center-right government party.) Salvini left the University of Milan several exams shy of a history degree to become a Northern League activist.

Despite his long political career, though, his intellectual and ideological evolution is hard to pin down. Before leaving college, Salvini had contemplated writing a thesis on the Italian industrialist Adriano Olivetti, a Catholic socialist with innovative ideas on improving society. “He said, ‘I can’t graduate, I’m obsessed with politics,’” Giulio Sapelli, a professor of economic history at the University of Milan whom Salvini had asked to advise on the thesis he never wrote, told me. Back then, Sapelli said, he’d recommend books to Salvini—Paul Kennedy’s The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, books by Henry Kissinger and the French philosopher Simone Weil, as well as Emmanuel Mounier’s The Personalist Manifesto, a book he said Salvini “appreciated a lot.” Mounier founded Personalism, an anti-Marxist school of thought that valued the individual. Sapelli told me he didn’t really recognize the youthful Salvini in the Salvini of today. “He’s a very different person,” he said.

Salvini’s performative talents were evident at a young age. As a teenager, he excelled as a contestant on Italian television game shows. In 1993, when he was 20, Salvini was elected to the Milan City Council with the blessing of the Northern League’s cigar-chomping leader and co-founder, Umberto Bossi. (Bossi was among those charged in the party-funding scandal.) A few years later, Salvini became a journalist for La Padania, the Northern League newspaper, where he edited letters to the editor. But his real breakthrough came in 1999, when Bossi plucked him to work for Radio Padania Libera, the Northern League’s rough-and-ready talk-radio station, known for its call-in programs. Here, Salvini excelled at fielding questions from (often angry) listeners.

“It was a great school,” Alessandro Morelli, a Salvini loyalist who ran Radio Padania after Salvini and is now a League lawmaker who was head of the Italian Parliament’s transport committee in the previous government, told me. “It’s the only radio that lets people call up without a filter.” The hosts picked the hot topics of the day and took the pulse. Salvini was a natural. To this day, he comes alive in the rapid-fire give-and-take of a press conference or a television debate. (He has also benefited enormously from the relative docility of the Italian press, which tends to focus obsessively on minor political tensions rather than the bigger picture—and which tends to cozy up to power. Some of Italy’s most popular television hosts and newspaper columnists aided in Salvini’s ascent by writing favorably of him, flattering him or letting him talk about how he gained weight on the campaign trail rather than asking him probing questions.)

As we sat in Morelli’s office in Parliament—he’d arrived late, fresh from a meeting with Salvini at the interior ministry, he said—I pressed him for anecdotes about Salvini’s Radio Padania days. Surely he must have a few good stories? No, Morelli said, nothing came to mind. Really? No, really, he told me. Just that Salvini was a great leader and a great communicator.

Morelli’s remarks—friendly and polite, yet vague—fit a pattern: The League is an extremely disciplined party, especially under Salvini. When they don’t talk, they don’t talk. And the few who do tend to say the same thing. League members told me so often that Salvini was his own media strategist—“Who’s Matteo Salvini’s spin doctor? The answer is Matteo Salvini,” Morelli told me, unprompted—that it began to sound like a kind of self-incrimination. Sure, Salvini understands that cat videos and attacks on immigrants get traction online, but the more his loyalists preemptively dismissed the idea of algorithms guiding his message, the more I began to suspect that his secretive social-media machine may be even more significant than what little of it the public knows.

Salvini wouldn’t grant me an interview, and neither would many of the League’s top officials. It and the Five Star Movement have mostly shut out the foreign press. Their brand of populism means controlling their own message. Salvini did deign to speak to Time, which put him on its cover as “the most feared man in Europe.” Things weren’t so different under Berlusconi, and it’s not uncommon for European leaders—Angela Merkel, Vladimir Putin, and Orbán, for example—to decline interviews with foreign media, but there’s one difference in Italy today, with Salvini (and the Five Stars) setting the tone: No western European G7 country has ever been run by such an inward-looking government in the postwar era.

Over the years, Salvini has shown consistency in a handful of areas: skepticism about the EU and the euro; anger at the perceived threat immigration poses to Italy; a belief in the traditional heteronormative family; and an admiration for autocrats.

In his 2016 autobiography, Secondo Matteo (“According to Matteo”), Salvini compares the EU to a “‘Super State’ that’s not that different from the old Soviet Union.” Never mind that the EU never sent anyone to the gulag; Salvini captures genuine frustration in Italy with the euro. The country didn’t manage the transition from the lira particularly well, with prices rising sharply compared with salaries, and to this day, many Italians blame their economic woes on the single currency.

Those feelings multiplied in Italy after the European debt crisis began, sending borrowing rates soaring and toppling governments in Greece, Spain, and Italy. By the fall of 2011, Berlusconi was out of power, stepping down when Italian bond yields were so high that it looked for a minute like the country might need a bailout. He was replaced by a government of national emergency led by Mario Monti, a technocrat, which had support from both right and left. (The League was in the opposition.) Monti’s government put in place austerity measures, including raising the retirement age, which the populist government had been working to reverse—although where Italy would find the money is anyone’s guess.

Where Salvini stands on the euro remains ambiguous. The League has governed for years at the local and regional level in Italy’s richest northern regions, home to businesses that have thrived under the euro, but when Salvini first took over the League, he, Morelli, and a few others drove a camper around Italy campaigning for 2014 elections for the European Parliament on a platform of “Basta euro,” or “enough already” with the euro. The effort was masterminded by Claudio Borghi, who was head of the Italian Parliament’s Budget Committee until the government fell. When I met him in his palatial office in Parliament this spring, he told me leaving the euro was no longer on the table—because the League governed in a coalition “whose program doesn’t include leaving the euro.” Salvini and other senior League officials have said they want the EU to change its rules, including the one requiring countries using the euro to keep their budget deficits under 3 percent of GDP.

This would require changing European treaties, which is a long shot. It’s also too technical for most voters to comprehend. Instead, Salvini rails against what he calls a Europe run by “bankers, do-gooders, and bureaucrats.” And he often singles out the billionaire financier George Soros in conspiratorial tones. In Salvini’s speech in Milan before European Parliament elections in May, he accused some “elites”—Merkel, France’s Emmanuel Macron, Soros—of betraying Europe, and said Soros was paying NGOs to bring immigrants to Europe. Is his targeting of Soros not a classic anti-Semitic trope? I pressed Borghi on this. “Salvini talks about Soros because he’s a speculator, not because he’s Jewish,” he said. The Hungarian-born financier was indeed a currency speculator in the ’90s, but Salvini mentions him only in the context of immigration. Here Italy seems to be following Orbán’s Hungary: a country with few Jews but dog-whistle anti-Semitism.

Salvini has long been obsessed with immigration as a negative force in Italy. When he was growing up, his family moved to a new apartment, only to find that the previous tenants refused to leave. “Strange to say it, but history repeats itself: The tenant wasn’t an Italian!,” Salvini wrote in Secondo Matteo. (The book’s title, with its clever reference to the Gospel according to Matthew, is trademark Salvini: at once grandiose and ironic about his own grandiosity. This strategy is key to his image—he plays the strongman but winks at the audience. He acts tough but disarming at the same time.) In 2009, when Salvini was a member of the Milan City Council, he suggested the city consider reserving special seats on public transport for “the Milanese” and for “people with good manners”—the implication being that foreigners didn’t meet that criteria. His critics at the time, including in the party then led by Berlusconi, said Salvini’s suggestion was reminiscent of asking Jews to wear yellow stars.

In speeches and in his autobiography, Salvini more than flirts with the rhetoric of the “great replacement” theory, most recently elaborated by the French philosopher Renaud Camus, who posits that Europe’s white-majority population is being replaced by people of color. This conspiracy theory has been adopted by far-right extremists, including the perpetrators of recent mass shootings in the United States and New Zealand. Salvini has not endorsed such violence, but nor has he backed away from a theory that has motivated it. (The Italian investigative journalist Claudio Gatti has reported in a recent book that one of Salvini’s closest friends in high school went on to become a leader in Forza Nuova, a neofascist group that has celebrated Salvini, and that the two men have remained friends for decades.) In 2016, Salvini went so far as to call the arrival of immigrants to Italy “an ethnic substitution.” Salvini offers a watered-down version of this claim in Secondo Matteo. “Italy today isn’t undergoing a phenomenon of immigration but a real and true substitution: Our young people are leaving and being replaced by foreigners,” he writes.

To counter this, Salvini proposes French-style bonuses to boost the birth rate—but only for families of Italian citizens. “We want to return to the joy of being able to have children without resorting to the horror of population change by means of out-of-control immigration,” he argues in his book. He never misses a chance to depict the left as people who will destroy families and harm children. In just about every rally and public speech, Salvini defends the traditional family against what he sees as the threat of same-sex couples, saying, “a family is a mamma and a papà.”

The League now has the governorship of Lombardy and the Veneto, and governs in a right-wing coalition in Friuli Venezia Giulia, Sardinia, the central Abruzzo region and Basilicata in the south, and has been gaining strength at the municipal level across once-left-leaning Tuscany, Umbria, and Emilia Romagna. (The latter two hold regional elections this fall.) Even if the new government has pushed the League into the opposition nationally, the party remains strong across Italy.

Salvini may be a traditionalist, but he’s not a moralist. He has two children from two different relationships: an elementary-school-age daughter, Mirta, and a teenage son, Federico. He constantly posts pictures of them on social media. He talks a lot about being a dad and about the challenges to staying married. (He never depicts himself as a son; his parents are all but invisible, although he does mention pearls of wisdom from his grandmother.) Salvini is now dating Francesca Verdini, a 26-year-old restauranteur whose father is a former Berlusconi ally convicted of misuse of public funds and of organizing an illegal Masonic lodge. The couple made their first public appearance this spring at the Italian premiere of Dumbo. Italian tabloid magazines—popular with older women who were crucial members of Berlusconi’s electorate—showed Verdini doing a walk of shame the next day, wearing Salvini’s clothes, an image that winds up making him seem virile.

By his own admission, Salvini has never been particularly religious, but in his efforts to court voters, especially in the south, he has taken to brandishing rosaries and crucifixes in his public appearances, an image that nationalizes his message of “Italians first.” It goes beyond left and right; it’s about defending Christian values. This has also opened a debate in Italy about the political instrumentalization of religious symbols. (By contrast, in France, Le Pen has cast herself as a great defender of French laïcité, an insistence on the absence of religion from the public sphere.)

In my quest to try to understand where to place Salvini, I paid a visit to Gennaro Sangiuliano, the head of the Italian state broadcaster RAI’s Tg2 news program, which has become a crucial part of Salvini’s media machine—one newspaper nicknamed it “Telesalvini”—and asked him what Salvini believed in. Sangiuliano is Neapolitan, and his discourse tends toward the baroque. Whenever I’d ask about Salvini’s strategy, Sangiuliano responded with long discourses on philosophers and scholars. He is the author of several books, including The Fourth Reich: How Germany Subjugated Europe, as well as biographies of Winston Churchill, Hillary Clinton, and Putin, whom he admires. At one point, Sangiuliano began a detour into American history and an (inaccurate) discourse on the origin of the word conservative, which he said came from a word for a person who in ancient tribes kept the flame alive. Then, finally, Sangiuliano answered my question. “I think—I think, I don’t know—that Salvini believes in conservative values, in the sense of returning to the old values of God, fatherland, family,” he told me.

These three words have more than echoes of the pillars of fascism. And Salvini is well aware of that. In May, he gave a campaign speech from the same balcony in the city of Forlì from which Mussolini once spoke. Salvini’s supporters include CasaPound, a far-right group that relishes demolishing Roma encampments on the impoverished outskirts of Rome. (It takes its name from Ezra Pound, who late in life defended Mussolini’s fascist regime.) Salvini has not disowned the group’s support, and has in fact made a point of ordering the bulldozing of Roma encampments. But he tends to downplay his own rhetoric by mocking it. Last month, just after Parliament passed a security bill that gives the interior ministry more powers, Salvini campaigned in Sabaudia, a beach town outside Rome, in front of a fascist-era memorial to Mussolini—surely a careful choice—and joked that he’d “get in trouble” for being there, saying he was surprised politicians on the left hadn’t had it torn down yet.

This ambiguity is at the heart of Salvini’s style: He taps into admiration for Mussolini while also winking at how such admiration is transgressive. In announcing he was withdrawing from the government, he said he wanted early elections and “full powers”—the exact words Mussolini used in the speech that brought him to power in 1922. Salvini’s defenders often dismiss concerns about his flirtation with fascist tropes as a kind of totalitarianism of the left. But Salvini’s behavior is always raising this question: Is he a fascist or a “so-called fascist”? Italy is a democracy, but with Salvini, something new has been unfolding. Ezio Mauro, a columnist for La Repubblica, has described it as “fascism 2.0.” “The growing and spreading banalization of fascism that has been under way in recent decades has had as a result the erasure of history, the removal of its meaning, the weakening of its judgment,” Mauro wrote. No, the tanks aren’t rolling in, he wrote, but the Italian right—and Salvini—need to clarify where they stand in their respect for the Italian constitution, the foundation of the Italian republic created after the Second World War, which Italy began on the side of the Axis powers and ended on the side of the Allies.

Even before his bare-chested beach tour, Salvini showed a soft spot for strongmen. He has professed great admiration for Trump, Orbán, and Putin. In Secondo Matteo, Salvini dwells on Putin’s visit to Milan in 2015. “I have to admit there has never been anyone in my life … who mesmerizes me the way Putin does,” he writes of the meeting. “His way of being, his decisive voice, his firm handshake: Everything confirmed that I was facing a real leader.” The League opposes European sanctions against Russia over its invasion of Crimea, on the grounds that they hurt Italian businesses. In this, the League is not alone in Italy, but it’s the only party in the country to have signed a cooperation agreement with Putin’s United Russia party, which it did on Salvini’s watch, in 2017. Heinz-Christian Strache’s Freedom Party in Austria and Le Pen’s National Rally signed similar accords with United Russia.* After Le Pen’s party signed the agreement, it secured a loan from a Russian bank. The League has said that no money changed hands in its agreement.

Yet the relationship with Russia could damage the League’s credibility. In recent months, the Italian magazine L’Espresso and BuzzFeed News have published damning scoops about a meeting in Moscow last fall in which close associates of Salvini discussed an energy deal that allegedly would have diverted funds to the League ahead of European Parliament elections in May, in violation of Italian campaign-finance law. In July, BuzzFeed published audio recordings of the meeting—one of the clearest signs to emerge yet of how Russia is trying to influence and destabilize European politics. There’s no evidence that the energy deal happened, and Salvini and his associates have denied wrongdoing, but magistrates in Milan have opened an investigation.

Salvini has refused to answer specific questions from journalists or members of Parliament. So far, the scandals haven’t stuck. Berlusconi’s scandals didn’t stick either. The Italian electorate tends to take a pretty dim view of the ethics of politicians.

Until the government changed, Salvini had always been on the offensive. Although he excels at playing the victim, mostly he forces others to debate and challenge him on his terms. He has done this by weaponizing migration as a threat.

Under European law, countries must process would-be asylum seekers in the first country of arrival. Since 2014, more than half a million people—asylum seekers and economic migrants—have landed in Italy, a country that is home to 60 million people and is 80 percent coastline. Many of these migrants have been dispersed in ill-named “welcome centers,” where they are stranded for years, unable to work legally, subject to exploitation by organized-crime groups, until Italy processes their applications. This has created a powder-keg situation, especially in smaller towns unaccustomed to immigration.

For Salvini, as for Trump, the rhetoric of “invasion” is fundamental. Under this government, the nightly news on RAI became filled with images of dark-skinned foreigners arriving on boats on Italy’s shores, as well as more coverage of crime, often committed by people of color. There has been a new focus on Nigerian organized-crime groups operating in Sicily and the Italian south, even though the territory is still controlled by Italian groups. (Italy’s crime rate has dropped, though racist incidents are on the rise.)

The images of the boats arriving have persisted even though the flow of migrants to Italy dropped sharply after 2016, when the EU struck a deal with Turkey, paying it billions of euros in exchange for Ankara not permitting would-be asylum seekers to leave. The flow decreased further after Rome struck a questionable accord with Libya in 2017, in which the North African nation agreed to detain would-be migrants in camps that critics say violate the Geneva accords. “There is no invasion,” Flavio di Giacomo, the spokesman for the International Organization for Migration, which tracks migration and human trafficking, told me. “What’s changed is public opinion.”

In the fall of 2013, just before Salvini took over the League, there was a wave of public national solidarity after nearly 500 migrants died when their boat caught fire off the island of Lampedusa. “People said, ‘These poor people,’ and ‘Anyone who’s lost at sea should be saved,’” di Giacomo said. Not so today. The day I met di Giacomo this summer, there were reports from the U.S. border with Mexico of children being separated from their families. Things were bad all over, I pointed out. “Your country has antibodies,” di Giacomo said. How strong were Italy’s?

In Italy, Salvini has mastered turning complex problems like immigration into simple images—boats arriving, boats being turned away. Here he has made use of Laura Boldrini, a former spokeswoman for the United Nations High Commission for Refugees who was later elected to Parliament as part of a small left-wing party, eventually becoming speaker of the lower house. She has never lived down saying that she believed immigrants were a resource for Italy, and Salvini now depicts Boldrini in regular Twitter attacks as the embodiment—feminized—of everything wrong with how the Italian left handled immigration. At a campaign rally in 2016, Salvini held up a blow-up sex doll and said it was Boldrini, to cheers from the crowd. Ahead of the European Parliament elections in May, he hate-tweeted about her, saying that if she was voting for the center-left Democratic Party, that was just another reason to vote for the League.

For Boldrini, the equation is simple—Salvini’s support is built on the previous wave of migrants, and the threat of more to come. “He’s a bully,” she told me. Boldrini said that she’d received rape threats and death threats after Salvini’s blow-up-doll attacks, and that someone sent a bullet in the mail to her office. Since Salvini was always campaigning and rarely at the interior ministry, Boldrini began tweeting back at him with the hashtag “WhenDoYouWork?,” which briefly went viral. Roberto Saviano, the author and media figure who has lived under police protection for more than a decade because of death threats from the Camorra, the Neapolitan organized-crime group, has emerged as another vocal critic of Salvini. Salvini, in turn, attacks him regularly in speeches and has threatened to remove his police protection (a peculiar stance for a minister who had been overseeing the Italian police).

As it happens, I first encountered Boldrini in March of 2011, on Lampedusa, as the Arab Spring was just beginning to unfold but before the United States invaded Libya and enlisted a reluctant Italy in the operation to depose Muammar Qaddafi. Europe’s migration crisis was just beginning then, and the island’s small cemetery was filled with the unmarked graves of those who had died at sea. I asked Boldrini if she ever would have imagined, back then when she was still with UNHCR, how this all would have unfolded, and that one day a Salvini-like figure would have appeared in Italy. “In 2011 we couldn’t have imagined that,” she told me. And the European Union was slow to react. “There was a flow of people before they realized this isn’t an Italian problem or a Greek problem, but a European problem. It took too many years for them to understand this.”

But Salvini hasn’t exactly been working to get more European help. This summer, he skipped a meeting of other European interior ministers, hosted by France, to discuss immigration. People familiar with the inner workings of the former government say he lacks a command of policy and avoids situations where he feels out of his depth. “They ask technical questions and he doesn’t know the answers,” Stefano Folli, a columnist for La Repubblica, told me.

What Salvini excels at is propaganda. “Stranding people at sea isn’t a policy, it’s media,” Nathalie Tocci, the director of the Institute for International Affairs, a Rome-based think tank, told me. Immigration—that is, the number of arrivals to Italy on boats from North Africa—is a concrete, governable issue, one that it’s not in Salvini’s interest to solve. “He’s built his whole political career on this, so what happens when the barbarians leave?” Today, every time a boat with 50 people is stranded off the coast of Italy, Salvini makes a federal case. “This isn’t management,” Tocci said. “This is cinema. It’s a fiction. It’s a shame.”

But lately Salvini has championed some policy changes. Newly approved security bills give the interior ministry far greater powers and further criminalize illegal immigration by imposing fines on boats that rescue migrants from drowning at sea, in possible violation of international search-and-rescue norms and the Italian constitution. The legislation also cancels “humanitarian protection,” a status that gave people the chance to apply for asylum in Italy if they’d been found to have been victims of torture or human-rights violations not only in their country of origin but also in a country of transit—such as the detention camps in Libya. This change is significant, but too technical for most voters to process.

And that’s where Salvini’s social-media skills come in. Just before announcing that he wanted to withdraw from the government, Salvini tweeted a video of two black men fighting in the street in Padua, which is governed by the center-left Democratic Party, with the words “Scenes from tolerant and welcoming” Padua. “And then those do-gooders call my Security Decree ‘inhumane’ and Salvini ‘criminal,’” he wrote. The next day he tweeted a video of a man he said was Nigerian, washing himself in public in Salerno. “He was washing himself completely naked in public, upsetting people in Salerno. Is this the ‘style of life’ that someone on the left wants as our ‘future’?”

In almost every public appearance and on social media, Salvini preemptively says that his critics like to call him “a racist” and “a fascist,” and even “a Nazi,” but he claims to be color-blind. “You can have brown, green, red skin,” he said at a recent rally, as long as you respect “our traditions.” His posts are racially coded, and he has shifted the debate to a kind of clash of civilizations that transcends a traditional right-versus-left frame. Catherine Fieschi, the author of Populocracy and a scholar of populism, told me she sees Salvini’s approach as a kind of “nationalism of the ignorant.” It’s less about “superiority and inferiority, but an incompatibility between cultures and values.” Either you’re one of us, or you aren’t. “People tend to think of populism as a politics of emotion. I don’t think it is emotion. That gives a bad name to emotion. It’s instinct,” she said. “You either know it in your gut or you’re not really one of us.”

Many politicians have capitalized on the emotional aspect of politics, but not all have Salvini’s fierce social-media operation. Salvini’s Facebook account has 3.8 million followers, and more engagement—that is, comments and reactions—than Trump’s, according to CrowdTangle, an analytics tool owned by Facebook. On Facebook, Twitter (1.1 million followers), and Instagram (1.7 million followers), he loves posting videos where he holds the phone himself, a pose that’s not entirely flattering and shows his bearded chin, now flecked with gray, but that lets him speak directly to the people.

Funny, self-aware, and sardonic, he disarms his own tough talk with self-deprecating humor. While Macron, another European leader of Salvini’s generation, acts like the smartest student in the class, Salvini comes across as the kid who might not have done so well in school but was always more popular, a bit of a rebel. He wears hoodies that say ITALIA and shows off his flabby stomach at the beach. He talks about his difficulties quitting smoking. He’s relatable, the guy next door, talking common sense. “We’re not promising miracles,” Salvini says at all his campaign rallies. He just wants to make Italy great again.

Salvini’s social-media feeds are a window into the brain, or the stomach, of the average Italian. He loves emojis and posts lots of videos of cats and dogs, “our four-legged friends,” as he calls them, as well as food—spaghetti, Nutella, a glass of wine—and alternates these with clips of immigrants portrayed in a negative light. While the American president’s tweets often come as a surprise to even his closest advisers, there’s something slightly reverse-engineered about Salvini’s feeds, a canny combination of genuine personal charisma and extreme calculation.

To collect data on audience engagement, Salvini’s social-media team uses sophisticated media software nicknamed “The Beast.” The team of about a dozen people is led by Luca Morisi, a 30-something marketing expert and League loyalist. Morisi rarely gives interviews, but when he does, he stays on message—remember, Salvini is his own spin doctor. In an interview last year with YouTrend, an Italian polling and communications outfit, Morisi explained how he had encouraged Salvini to do more Facebook Live videos, which let him get his message directly to voters. “There’s a mirroring game with traditional media: The leader speaks in real time but then his words are commented on in the public discussion, such as in talk shows,” Morisi said then.

I spoke with Morisi in Milan at an event in April where Salvini and other far-right leaders from Europe had announced an alliance ahead of elections for the European Parliament. Pale and slightly elfin, Morisi wore AirPods and looked as if he hadn’t seen the sun in days. While Salvini campaigns in piazzas and beaches, Morisi runs the back office. I asked him whether he’d seen a connection between Facebook likes and political support. “There's a lot of symmetry between the two fields,” he told me, in fluent English. In the summer of 2018, for instance, Salvini closed Italy’s ports to a boat called the Aquarius, which was carrying hundreds of migrants, forcing it to dock in Spain. After Salvini posted about the boat, “we had this increase of likes on the Facebook page from 2 million to 3 million in just three months and in the polls from 20 to 30 percent,” Morisi told me. “There was a connection.”

(There may be other factors. A 2018 study, “Mainstreaming Mussolini,” by ISD, a nonprofit aimed at fighting extremism and polarization, found that far-right groups in the United States and Europe had been working with far-right Italian organizations online to drum up support for the League and the far-right Brothers of Italy party ahead of the 2018 national elections. The New York Times has also reported that an Italian site promoting pro-Russian news shared a Google tracking account with Salvini’s official campaign site, as well as with other pro-Kremlin sites.)

Morisi attributed Salvini’s success to his ability to dominate in three arenas at once: social media, television, and the piazza. Then there are the selfies. In March, I followed Salvini on the campaign trail ahead of regional elections in Basilicata, the instep of the boot, the poorest region of Italy, an area, like so many in the Italian south, whose chief export may well be its emigrants. I wanted to see how he was faring among voters who had so recently been the appointed enemy of the then–Northern League. It turned out he was doing very well: Basilicata voted for the Five Star Movement in national elections last year, but a center-right coalition including Salvini’s League won regional elections this spring.

What I witnessed in Basilicata was Salvini’s genuine, undeniable charisma. One morning in Muro Lucano, a town of 5,000 souls, a handful of older men wearing wool caps sat under a magnolia tree, not yet in bloom. People of all ages wandered into the piazza, and a local politician warmed up the crowd. “Do we want to throw out the left? Yes! Do we want change? Yes!” And then, soon, “Il capitano è in arrivo!” “The captain is coming! Move to the side, everyone will have time for photos!” With his Milanese accent, Salvini gave a standard speech—You are the masters of your own homes; let’s lock up immigrants who come here to deal drugs; I’ll block the ports, lower the retirement age, fix your broken health-care system.

But it was what happened after the speech that got my attention. I stood on a bench as people took selfies with Salvini, watching their faces as they emerged from the stage. They were glowing—as if they’d been blessed by a deity, or at least a celebrity. They felt seen. Their friends and family gathered around the phone screen to see the picture they’d snapped. Women called him un bell’uomo, a handsome man, and un simpaticone, a nice guy. Others called him una persona sincera, sincere. Un uomo concreto, down-to-earth. No other politician in Italy, or even Europe, today has anything near this kind of star power.

One evening in Tolve, a town of 3,200 people in Basilicata, hundreds gathered in the piazza to hear Salvini. He gave his usual campaign speech and at the end of the performance, after Vasco Rossi’s song Un Mondo Migliore, “A Better World,” blasted through the speakers, I chatted with a few people who’d taken selfies with Salvini. Vito Gruosso, 22, said he shared Salvini’s line on immigration. “I don’t think he’s a fascist or a racist. He’s for the rights of Italians. People who come from Africa, they should adapt to our country,” Gruosso told me. Salvini, he said, was “close to the people.” When I asked if he meant very present on social media, Gruosso and a friend nodded yes. “It helps make him seem normal,” Gruosso said.

This has been Salvini’s cleverest move: He has understood that being close to the people means being on their screens all the time. Buongiorno, amici! He is the man of the moment for a social-media age when outrage runs high, attention spans low, and historical memory lower.

Salvini’s gamble of trying to force early elections came up against one thing: He had the numbers in the polls, but not in Parliament. The selfies had gone to his head. The fear of a far-right government in Italy jolted the EU and the Italian ruling class enough that sworn political enemies reversed their previous positions entirely in order to team up. This alliance looks to be an uneasy one, based more on tactics than on policies. The differences of style, substance, and party organization run deep. Salvini has already accused the new government of having been engineered by “Paris, Berlin, and Brussels.” His base remains strong.

What we’re seeing in Italy today is uncharted territory. The country is at the forefront of anti-politics politics. It is not a meritocratic place, but one whose networks of power often transcend left and right. Today, left and right, north and south have been scrambled into an angry, cynical, and disillusioned protest vote that elected a messy coalition in which government and opposition have been functionally interchangeable. In France, the “yellow vest” protest movement took to the streets for months with calls to depose Macron. In Italy, the equivalent of the yellow vests have been running the country since 2018.

Berlusconi may have laid the groundwork for Salvini, in his ability to disconnect image and reality. But Salvini has forged on in new directions, further divorcing words from meaning, or from consequences, banalizing some of the worst chapters of Italian 20th-century history. For months, as I’ve followed Salvini across Italy and watched his face rise to the top of my social-media feeds, I’ve thought back to some lines from Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism. She writes of people who come under the sway of autocrats, of the “curiously varying mixture of gullibility and cynicism with which each member ... is expected to react to the changing lying statements of the leaders.” This describes something in the Italian electorate, as does another passage from Arendt, in which she writes that “in an ever-changing, incomprehensible world the masses had reached the point where they would, at the same time, believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible and nothing was true.”

In the mid-1930s, not far from where I watched Salvini campaign in Basilicata this spring, Italy’s fascist regime sent Carlo Levi, a doctor, writer, and painter born into a Jewish family in Turin, into internal exile as punishment for his antifascist activism. He wrote about this, and about the poverty he witnessed in Basilicata, in his haunting 1945 novel, Christ Stopped at Eboli. Levi described the mentality of people who had been governed by foreign rule, including that of Rome, for centuries. This part of the south, he wrote, was a land of family ties and tenant farming, an economy that hadn’t changed much since feudalism. It was a place, he said, that resisted the very notion of progress. Today it feels bypassed by the global economy.

As I looked at the faces in the crowds of Salvini’s rallies in Basilicata, I thought of Levi. Some had come out of curiosity, or because Salvini was a rare government minister who had deigned to pay a visit. But there was something more. They wanted to be in his presence. They wanted to be close to power. In their eyes I saw resignation but also hope. No matter that the League faced corruption scandals, or that Salvini admired autocrats like Putin and Orbán. These were the faces of people who felt left behind. They were fed up, and Salvini seemed to understand. He saw them. He took pictures with them. They wanted change, and he seemed like change. Some were waiting for a strongman, others for a leader. And, well, when they looked out on the horizon, Salvini was the only one they could see.

* This article originally misstated the Austrian political party that signed a cooperation agreement with United Russia. It was the Freedom Party, not the People’s Party.