Beirut's waterfront speaks of opulence and wealth. Yachts fill the new marina which lies beneath the shadows of newly-built, high-end high-rise hotels.

Well-heeled visitors walk casually along the sun-drenched boardwalk, stopping to browse in the expensive shops or pay over the odds for lunch in one of the Lebanese capital's many fashionable restaurants.

The scars of a war-torn country appear to be healing. But this is a city of two tales. The second is a tale of poverty and desperation, more familiar and representative of life for many in Beirut.

In the southern suburbs, a little more than a 15-minute Uber ride from the waterfront, lies Shatila, a densely populated ghetto, an area with such a notorious reputation, most Beirut natives have never set foot in it.

In the minds of most, Shatila represents chronic poverty, criminality and drugs, with danger lurking at every turn through its dark alleyways. Yet Shatila is also home to a resilient community, one that survives on its own self-contained economy and the strength and industry of its people.

Shatila was hastily built in 1948 as a refugee camp for Palestinians escaping the war with Israel. Today, over 20,000 people live in a one square kilometre area. Palestinian militants control the camp.

The Lebanese authorities avoid the area, leaving the community to manage its own affairs. Palestinian organisations, Fatah and Hamas, form the de facto government in this ghetto. Palestinian flags fly proudly throughout. This enclave is Palestinian in everything but GPS location.

I’m joined at the main entry point in to Shatila by Emily Whitehead, Trócaire’s director in Lebanon. Emily has arranged for aid workers from Basmeh & Zeitooneh, a grassroots community organisation, to accompany us in to the camp. It’s one of Trócaire’s many partner agencies helping to deal with the refugee crisis in Lebanon.

Amal, Ghifar and Sana, three women who have been working tirelessly with refugees in Shatila, come to greet us. Permission to enter the camp has been sought and secured from Palestinian militants controlling the ghetto by a reliable contact. However, I’m advised to hide my camera equipment as we walk through specific streets and that certain buildings cannot be filmed under any circumstances.

I’m hoping to meet a Syrian family who have fled the war and found refuge in Shatila. The steady flow of Syrians since 2011 has swelled the population in the camp, doubling it according to some estimates.

Lebanon is struggling under the weight of the sudden influx from Syria. The United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR) estimates that there are just under one million Syrians in Lebanon at present. The Lebanese government and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) say the number of displaced Syrians in Lebanon is closer to 1.25m. That’s almost a quarter of the country’s entire population.

As we make our way through Shatila, the narrow winding streets are a labyrinth of poverty. Those in clapped-out cars, on bicycles and mopeds compete with pedestrians in the three-metre wide tracks.

Street-hardened children play and roam as they please. The stale smell of rancid waste water mingles with the rich aromas of the street stalls.

Streets are lined with traders turning their hand to anything that will sell. Overhead, stretching between the buildings, hangs a tangled cobweb of electrical wires.

The intermittent electricity supply here is driven by diesel generators, while homemade electrical solutions create a deadly hazard hanging a couple of metres above our heads. The water supply is undrinkable and sanitation services in Shatila are chronically insufficient.

We quickly weave our way through the chaotic hustle and bustle, before swinging right on to a quieter, narrower alleyway.

We then pass through a gate and enter the back of one of the crumbling concrete buildings. Amal knocks on a door. We are greeted by a friendly-faced young woman. Her playful children excitedly scamper about her.

Her name is Elham and she invites us in to her two-room flat. Her kitchen area is nine feet by six feet, enough to hold storage units, a hand basin, a cooking stove and small kitchen counter.

The second room is dark and has one large double bed against the wall and a small table in the centre. Clothes are neatly piled on the far side of the room. The walls are decorated with distant memories of home, photographs of relatives, many lost, including her husband.

The tiny space is tidy and proudly maintained by Elham. With the help of Sana, our translator, Elham proceeds to tell us her story.

"I came here with my husband and our three children five years ago. We fled the war. Then my husband returned to Syria to help get his sister out but he was killed. It was a terrible shock. I did not know what to do."

Elham and her children are in virtual 'limbo', the family’s identity documents having been destroyed during the war in Syria. Without an income to sustain the family, the widowed mother is heavily reliant on the food programme offered by Basmeh & Zeitooneh.

As well as food relief, the organisation offers support for the renovation of shelter, training and education programmes. The agency has helped Elham secure schooling for her three children. Its small office is an oasis of comfort in the midst of the desperation.

In the face of poor infrastructure and fragile institutions the Lebanese government says it doesn’t possess the means to support so many refugees. The Trump administration’s decision to cut its funding for UNWRA (the UN’s relief agency for Palestinian refugees) from $360m in 2017 to zero this year has dealt a traumatic blow to aid efforts in Lebanon.

Last May, the government, through its Higher Defence Council instated a new deportation policy as one of several measures to increase pressure on refugees to return to Syria. Other measures include the forced demolition of refugee shelters and a crack down on Syrians working without authorisation. Between 21 May and 28 August 2,731 Syrians were deported.

Emily Whitehead of Trócaire says the change in government policy has the Syrian community in Lebanon living in fear.

"The fear of being deported is real. 78% of Syrians do not have the right paperwork because of bureaucratic hurdles and the cost of getting that paperwork. If they are arrested by the authorities there’s a risk they could be deported and given straight back to the government of Syria without having their case and claims for asylum heard," she said.

Despite the terrible living conditions, places like Shatila appeal to refugees who fear deportation. Shatila is recognised as a 'no-go' area for authorities and therefore offers a safe sanctuary for unregistered refugees.

Their great difficulty, however, lies in the fact that once they are in, the chances of getting out and finding a better life beyond Shatila are greatly reduced. It also means they are extremely vulnerable to exploitation as they seek to protect their anonymity.

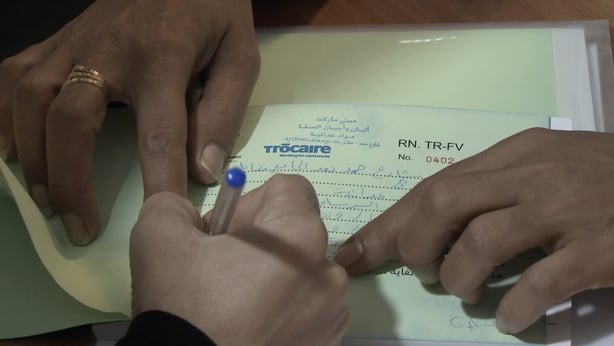

I accompany Elham as she seeks to collect her food voucher. Basmeh & Zeitooneh’s office is situated just off one of the busiest streets in the heart of Shatila.

We enter a dark corridor and climb two flights of concrete stairs. There she is warmly greeted by Amal who prepares her food voucher. Elham signs it. This piece of paper will ensure that she and her children won’t go hungry tomorrow.

Despite the harsh realities and the endless poverty of Shatila, Elham is grateful for the refuge and support she receives there and sees it as her only hope. Her hope is not for herself, but is that which she has invested in her children.

"I can’t return to Syria. There is nothing there for us. I must remain here and try to find a better life for my children. I am happy to sacrifice my own life for them. It is my duty as a mother. I have dreams for their future."