Sperm donation after death is 'morally permissible' to meet UK donor shortage

Researchers envisage a situation where men could indicate during life that they have a preference to donate sperm after death.

Tuesday 21 January 2020 06:29, UK

Sperm should be added to the list of human tissue that can be donated after death, academics say.

There is currently a UK-wide gap in supply, with samples imported from foreign sperm banks in order to keep up with demand, according to the experts.

"It is both feasible and morally permissible for men to volunteer their sperm to be donated to strangers after death in order to ensure sufficient quantities of sperm with desired qualities," say Dr Nathan Hodson of the College of Life Sciences at University of Leicester, and Joshua Parker of the Department of Education and Research at Wythenshawe Hospital in Manchester.

Writing in the Journal of Medical Ethics, the authors argue it is important to secure a reliable source of sperm, given "the immense value of having the ability to reproduce".

While infertility is not considered a life-threatening disease, "life-enhancing" transplants from living donors, for example corneal transplants, currently take place.

They say: "If it is morally acceptable that individuals can donate their tissues to relieve the suffering of others in 'life-enhancing transplants' for diseases, we see no reason this cannot be extended to other forms of suffering like infertility, which may or may not also be considered a disease."

They envisage a situation where men could indicate during life that they have a preference to donate sperm after death.

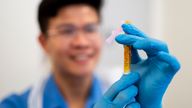

The sperm would be extracted after death either surgically or via electric shocks to the prostate to stimulate ejaculation. It would then be frozen until selection for use.

Dr Hodson and Mr Parker acknowledge concerns that health issues experienced by the donor may be passed to the child through genes carried by the sperm.

They say that this could be minimised by screening donors and sperm - safeguards already in place with living donors.

The "thorniest question" regarding the donor's family relates to their right to "veto" their loved one's wishes, an existing element of the UK's current solid organ donation policy.

They conclude: "Although this is a promising alternative method of obtaining donor sperm, several questions remain.

"Some of these questions parallel ongoing debates in organ donation, although the use of donated reproductive material might alter the nature of questions about consent and the family veto.

"Other questions regarding quality of consent and integrity of donor anonymity also have comparisons in living gamete donation.

"Finally, artificial reproductive techniques funding in the UK remains contentious, so it is unclear who would pay for voluntary non-directive postmortem gamete donation."