Red and Blue America Aren’t Experiencing the Same Pandemic

The disconnect is already shaping, even distorting, the nation’s response.

Updated on March 22, 2020 at 12:55 p.m. ET

Even a disease as far-reaching as the coronavirus hasn’t entirely crossed the chasm between red and blue America.

In several key respects, the outbreak’s early stages are unfolding very differently in Republican- and Democratic-leaning parts of the country. That disconnect is already shaping, even distorting, the nation’s response to this unprecedented challenge—and it could determine the pandemic’s ultimate political consequences as well.

A flurry of new national polls released this week reveals that while anxiety about the disease is rising on both sides of the partisan divide, Democrats consistently express much more concern about it than Republicans do, and they are much more likely to say they have changed their personal behavior as a result. A similar gap separates people who live in large metropolitan centers, which have become the foundation of the Democratic electoral coalition, from those who live in the small towns and rural areas that are the modern bedrock of the GOP.

Government responses have followed these same tracks. With a few prominent exceptions, especially Ohio, states with Republican governors have been slower, or less likely, than those run by Democrats to impose restrictions on their residents. Until earlier this week, Donald Trump downplayed the disease’s danger and overstated the extent to which the United States had “control” over it, as the conservative publication The Bulwark recently documented. Conservative media figures including Rush Limbaugh and Sean Hannity likewise insisted for weeks that the media and Democrats were exaggerating the danger as a means of weakening Trump. Several Republican elected officials encouraged their constituents to visit bars and restaurants precisely when federal public-health officials were urging the opposite.

The disparity between the parties was underscored Thursday afternoon when Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti and California Governor Gavin Newsom, both Democrats, issued rapid-fire orders closing down all non-essential businesses, first in the city and then in the entire state, a jurisdiction of 39.5 million people.

This divergence reflects not only ideological but also geographic realities. So far, the greatest clusters of the disease, and the most aggressive responses to it, have indeed been centered in a few large, Democratic-leaning metropolitan areas, including Seattle, New York, San Francisco, and Boston. At Thursday’s White House press briefing, Deborah Birx, the administration’s response coordinator, said half of the nation’s cases so far are located in just 10 counties. The outbreak’s eventual political effects may vary significantly depending on how extensively it spreads beyond these initial beachheads.

If the virus never becomes pervasive beyond big cities, that could reinforce the sense among many Republican voters and office-holders that the threat has been overstated. It could also fuel the kind of xenophobia that Trump and other GOP leaders, such as Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas, have encouraged by labeling the disease the “Chinese virus” or the “Wuhan virus.”

“There’s a long history of conservatives demonizing the cities as sources of disease to threaten the ‘pure heartland,’” says Geoffrey Kabaservice, the director of political studies at the libertarian Niskanen Center and the author of Rule and Ruin, a history of the modern Republican Party. “That’s an old theme. So that could be how it goes down.”

Conversely, the charge that Trump failed to move quickly enough may cut more deeply if the burden of the disease is heavily felt in the smaller communities where his support is deepest. Most medical experts believe that, eventually, the outbreak will reach all corners of the country, including the mostly Republican-leaning small towns and rural areas that are now less visibly affected.

“There’s no reason to think that smaller communities will be protected from it,” Eric Toner, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, told me. “It may take longer for it to get there, but as long as there are people coming and going … the virus will eventually find its way to rural communities as well.”

Still, some experts believe that, throughout the outbreak, the greatest effects will remain localized in large urban centers. “The bottom line is, every epidemic is local, and the social networks and the physical infrastructure in any specific geographic area will determine the spread of the epidemic,” Jeffrey D. Klausner, a professor of medicine and public health at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, told me. “Particularly, respiratory viruses are dependent on close social networks and are going to spread much more efficiently in crowded, densely populated urban areas.”

The tendency of Democratic-leaning places to feel the impact first reflects the larger economic separation between the two parties. Democrats now dominate the places in the U.S. most integrated into the global economy, which may be more likely to receive international visitors or see their own residents travel abroad.

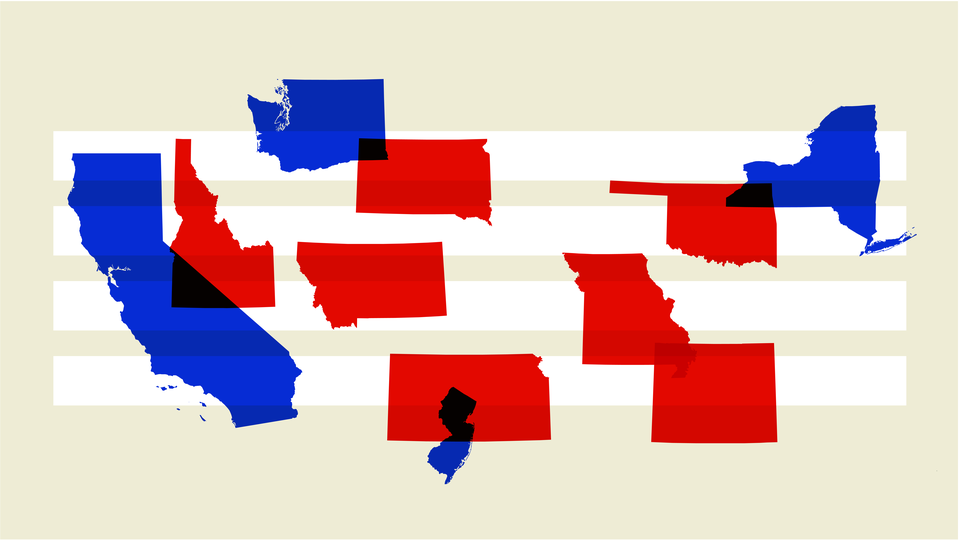

On the case-tracking website maintained by Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Systems Science and Engineering, each of the four states with the largest number of coronavirus cases is a Democratic-leaning place along the coast: New York, Washington, California, and New Jersey. Florida, a coastal, internationally oriented state that leans slightly toward the GOP, ranks fifth. Illinois, Louisiana, Massachusetts, and Texas, each with at least one big urban center that functions as a gateway for tourism and trade, come in next. And though the Johns Hopkins project isn’t publishing precise county and municipal data on the outbreak, the biggest clusters of disease have all erupted in a few large metropolitan areas.

Toner said that while “it’s not universally the case” that pandemic diseases tend to spread first in the places most open to international travel, “as a general rule” that is the progression they follow. “The virus travels with people,” Toner said. “So, where people travel is where the virus goes first, and then it spreads out from those areas in which it has been introduced.”

By contrast, with only a few exceptions, the states with the fewest number of confirmed cases are smaller, Republican-leaning ones between the coasts, with fewer ties to diverse populations and the global economy. That list includes Wyoming, Idaho, Missouri, Montana, South Dakota, Oklahoma, and Kansas. (One important caveat: Testing in the United States remains deficient, so many cases are inevitably flying under the radar. “It’s not the case that other places don’t have cases,” Toner said. “They just don’t recognize them yet.”)

Republican-leaning states to this point are displaying notably less urgency about the outbreak. Of the states that have taken the fewest actions to restrict public gatherings or limit restaurant service on a statewide basis—such as Texas, Missouri, and Alabama—almost all have Republican governors, according to research by Topher Spiro, the vice president for health policy at the liberal Center for American Progress, where he directs a program that examines state health initiatives.

That’s left Democratic-run cities in those red states—such as Houston, Tucson, Nashville, and Atlanta—to try to impose their own rules on public gatherings. Yet all those local limits face an obvious problem: People from elsewhere in the state can still travel to their jurisdictions. “We can’t seal our borders,” acknowledged Lina Hidalgo, the chief administrator in Harris County, Texas, which includes Houston, when she announced county-wide closures on Monday.

The willingness to impose statewide rules hasn’t entirely followed party lines: Before his announcement in California on Thursday, for example, Newsom had couched proposals to shut restaurants, schools, and other establishments as recommendations, not requirements, thus permitting a patchwork of local responses. But generally, Spiro’s research found, almost all of the states that took the earliest and most dramatic statewide action, such as New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Illinois, have Democratic governors.

Public attitudes about the outbreak are separating along the same lines. The huge differences between Republicans and Democrats extend not only to assessments of Trump’s response to the outbreak but also to its underlying level of danger and the need to change personal behavior. If anything, there’s considerable evidence that those gaps are widening.

A national Gallup poll released Monday, for instance, found that while 73 percent of Democrats and 64 percent of independents said they feared that they or someone in their family might be exposed to the coronavirus, only 42 percent of Republicans agreed. That 31-percentage-point difference dwarfed the gap in February, when slightly more Republicans (30 percent) than Democrats (26 percent) said they were concerned.

Other surveys have found comparably stunning differences. In an NBC/Wall Street Journal poll released Sunday, Republicans were only half as likely as Democrats to say that they planned to stop attending large gatherings, and just one-third as likely to say that they had cut back on eating at restaurants. In an NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll released Tuesday, just over half of Republicans said the threat from the virus had been exaggerated, compared with one in five Democrats and two in five independents.

In a nationwide Kaiser Family Foundation poll released the same day, about half of Democrats and Democrat-leaning independents said the outbreak had disrupted their life at least some, according to detailed results provided to me by the pollsters. But only one-third of Republicans and those who leaned Republican agreed. About half of Democrats said they had changed travel plans and decided not to attend large gatherings. In both cases, less than one-third of Republicans agreed.

Kabaservice says the tendency of GOP voters and officials to downplay the risk partly reflects Trump’s initially dismissive messaging about the crisis. But it may also relate to a deeper ideological suspicion of scientists, the media, and subject-matter experts within the federal government.

“This is something we’ve gone through a while here among Republicans,” Kabaservice says. “The feeling increasingly is that experts and the media are all part of this elite class that is self-dealing and is looking down on less-educated and less-fortunate people, and [that] they can’t be trusted to tell the truth.” He adds, “That dynamic … has been reinforced” by the emergence of the “conservative media ecosystem,” which unstintingly presents “elites” as a threat to viewers.

The parties’ contrasting geographic bases of support may also have an influence. Recent public polling has found an imposing gulf in attitudes between urban and suburban areas on one side and small-town and rural areas on the other.

In the Gallup survey, two-thirds of urban residents and three-fifths of those in suburbs said they were concerned about someone around them contracting the coronavirus, while only about half of those living in rural areas agreed, according to detailed results provided to me by Gallup. (That town-and-country gap had widened since February.) In the Kaiser poll, more than two-thirds of rural residents said the outbreak had disrupted their life little or not at all, while nearly half of urban residents said they had already experienced disruption. Additionally, rural residents were almost twice as likely as those in urban areas to express confidence in Trump’s handling of the crisis.

Eva Kassens-Noor, a professor in the global-urban-studies program at Michigan State University, studied urban/rural patterns in the 1918 flu pandemic in India. Her research found that mortality was much greater in urban places above a certain density level than in rural places below it. She believes that U.S. communities will experience the coronavirus in contrasting, but complex, ways: While the disease will probably spread more rapidly in urban areas, she says, more of the population there is young and healthy. And while outbreaks may not be as pervasive in rural America, they could still prove very damaging because the population is older and has less access to quality health care.

Mortality rates, she says, will ultimately hinge on how rigorously communities minimize interaction by practicing social distancing. “It is all about individuals closing all of their social networking,” she says.

More penetration of the virus into reliably Republican rural regions probably won’t erase the partisan gap in perception of the danger. The Republican pollster Bill McInturff, whose firm Public Opinion Strategies co-manages the NBC/WSJ poll, says that even Republicans in and around big cities remain much more dubious of the threat than their Democratic neighbors.

But if the outbreak becomes more widely dispersed over time, it may be tougher for even the most conservative governors to resist action—or for Trump to escape consequences for his initially dismissive response.

“Seattle, San Francisco, New York, Boston are just a few weeks ahead of other parts of the country,” Toner said. “There will be outbreaks in places that we will be very surprised by. I am quite confident about that.”