The first time photographer Chris Burkard encountered the desolate beauty of Iceland, it took his breath away.

“It was a visceral experience,” he said over the phone from his home in central California. “It felt like it extracted a piece of my heart.”

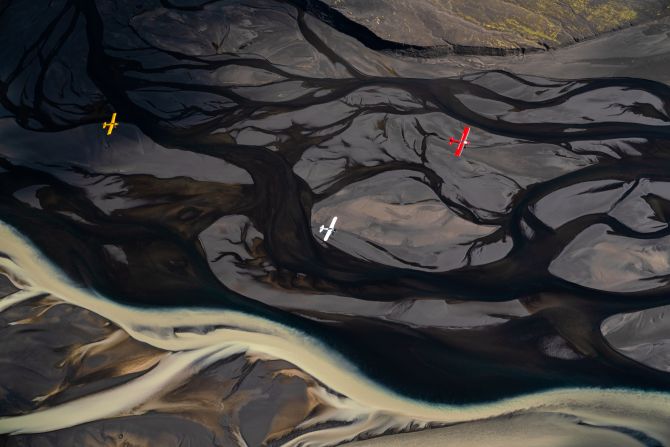

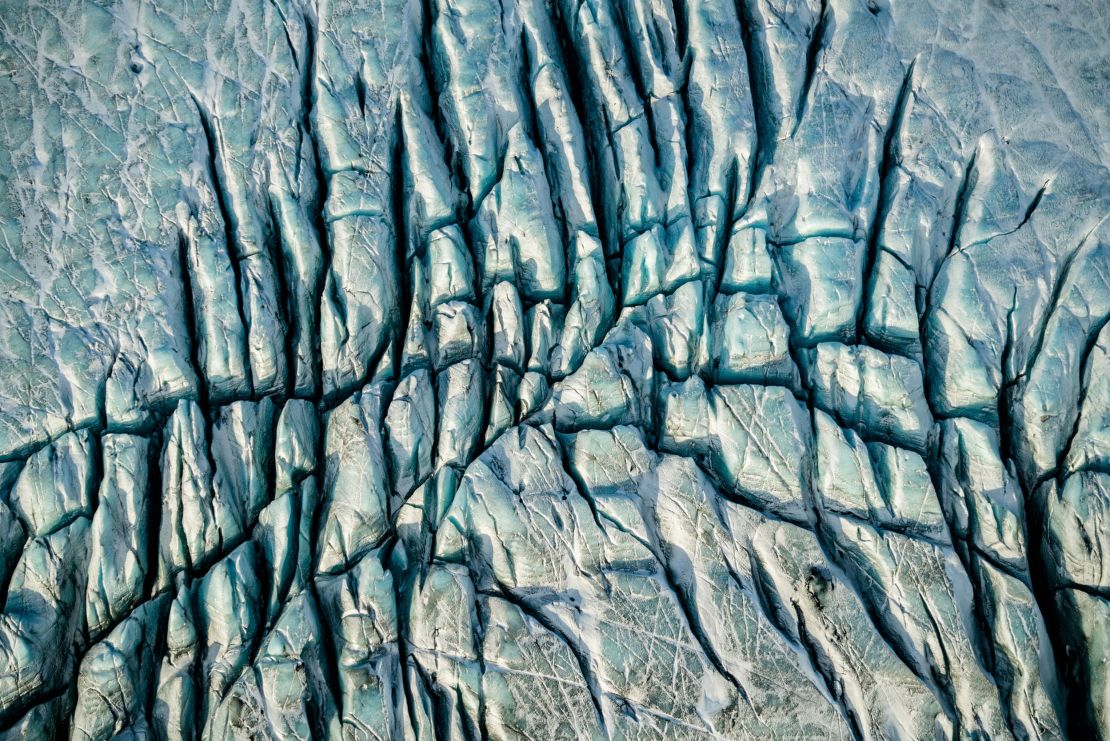

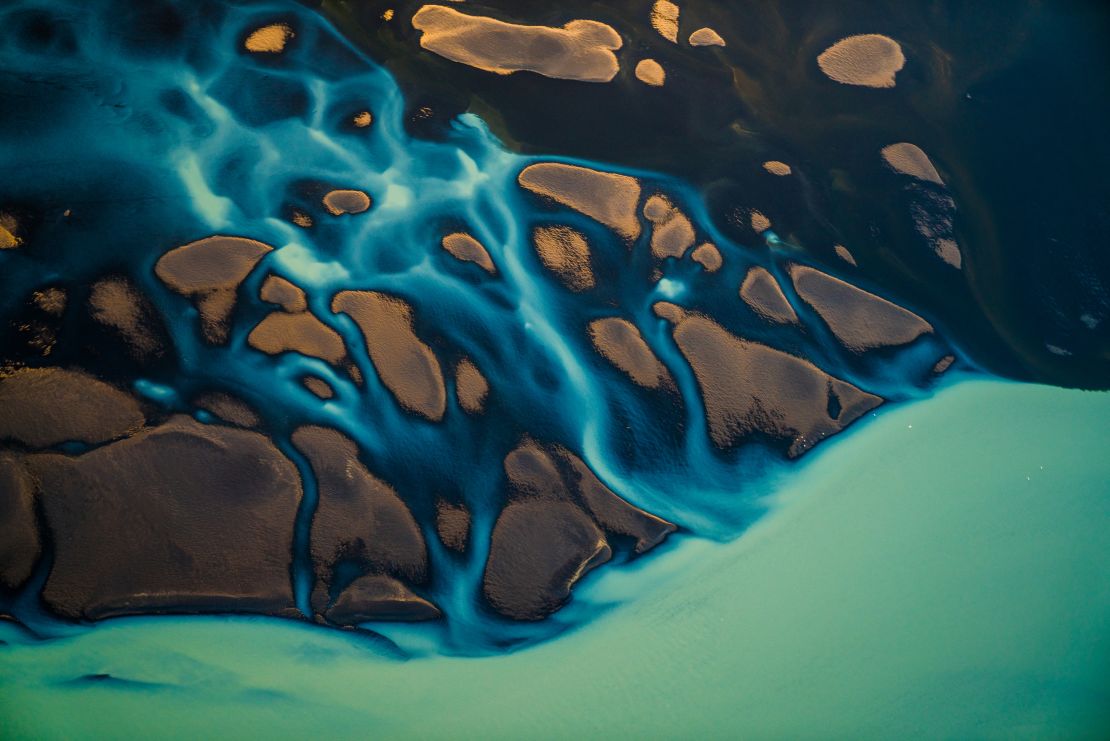

Burkard’s recently released book, “At Glacier’s End,” is a love letter to the country’s rivers. Shot from a plane 2,000 to 4,000 feet in the air, the waterways become painterly abstractions, winding from icy glaciers to the open seas. But the book isn’t just about the allure of Iceland’s topography – the rivers that Burkard has captured for more than seven years are disappearing, as dams are built to increase the country’s hydropower energy.

In the book, Burkard and writer Matt McDonald tell the story of the uncertain future of Icelandic waters.

Painterly aerial views of Iceland's glacial rivers

Burkard’s first trip to the Nordic island nation was more than a decade ago, when he was a travel and surf photographer sent on assignment.

The photographer, who grew up in a small coastal town halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco, chose a career that would allow him to explore the world, an opportunity not afforded to him until adulthood. However, after years of shooting editorials in idyllic locations that promised adventure but catered to tourists, Burkard became somewhat disillusioned with finding fulfillment.

“I started to go places that I knew were going to feed my soul in a different way, because they required more of me,” he said. Even the most beautiful vistas he had seen paled in comparison to the untamed wilderness of Iceland’s vast Highlands, an inhospitable plateau that rises from the sea and features black-sand deserts, monolithic glaciers, jagged volcanos and intricately braided rivers.

To Burkard, who was accustomed to the verdant, wooded lands of the High Sierra and Big Sur, Iceland’s often stark panoramas felt alien.

A project years in the making

To date, Burkard has traveled to the country more than 40 times, but it took years for him to begin shooting the body of work that makes up “At Glacier’s End.” He was traveling from Ireland to Iceland, on a different route than he was used to, when he looked out the window and saw the sublime below him.

“(There were) these intricate patterns and vibrant colors spewing out of the river mouths and into the ocean,” he wrote in a foreword for the book. “Visually it made no sense. It was a kaleidoscope of color breaking apart, like arteries full of blood and disintegrating into the ocean.”

Burkard promised himself he would see that view again. He eventually connected with a local pilot, Haraldur Diego, who took him over the country’s expansive river systems in a small red Cessna plane.

He was humbled by the views, as well as his lack of preparation. “The first time I flew over the rivers, I was there during the wrong time of year,” he recalled. “It was spring, and there was no water flowing. I learned that these rivers, much like an aurora or the moon, are cyclical. (It’s only) at certain times of the year that they’re flowing and rich and vibrant.”

As he returned to the air with Diego again and again, the pilot began to educate him not only on the locations and temperaments of the rivers, but their precarious state.

Iceland is touted for its leadership in renewable energy, with 65 percent of its output coming from geothermal sources, as of 2016. In addition, 20 percent comes from hydropower, at great cost to the environment. The massive and controversial Kárahnjúkar Hydropower Plant, completed in 2009, powers a single aluminum smelter but requires five dams on two rivers, including the Kárahnjúkar Dam, the largest of its kind in all of Europe.

“(Diego) flew me over some of the dried-up rivers and, and that was the moment that it dawned on me that this project had the potential to tell a much bigger story,” Burkard recalled. “If you spend enough time in these wild places, you begin to feel a responsibility to protect them. It’s just inevitable.”

Sharing the view

Burkard is cognizant of those who have documented Iceland’s rivers before him, including Andri Magnason, the author and one-time presidential candidate whose highly influential 2006 book, “Dreamland” was adapted to a documentary film. And despite working with environmental activists and speaking at a conference organized by the country’s Ministry for the Environment and Natural resources, Burkard is reluctant to call himself an environmentalist.

“I know that my job (requires) me to travel and burn emissions,” he said. “But I am also very realistic about the fact that if I can advocate for places I love – places I fear losing – then there’s the potential to inspire others to form a relationship with them, too.”

For many people in the world who can’t experience Iceland’s wild vistas for themselves – as Burkard could not when he was growing up in California – he hopes that it will illuminate the country’s fragile beauty, which he considers an artwork much greater than his own images.

“Iceland is magical,” he said. “In many ways it haunts me. It keeps me up at night, thinking that generations following mine won’t be able to experience it. I feel like this is my small contribution to that kind of artwork.”