Vancouver Chinese-Canadian photographer’s portraits of immigrants – black, Chinese, Sikh – a reminder of their role in building the city

- A curator’s curiosity was piqued when she kept coming across portraits of immigrant families in Vancouver taken by a Chinese Canadian, Yucho Chow

- Catherine Clement soon learned he hadn’t only shot Chinese subjects, and bit by bit uncovered Chow’s own story – that of a scrappy migrant, like his subjects

Catherine Clement began to notice the seals on old black-and-white photos more than 10 years ago, when the curator was interviewing Chinese-Canadian veterans of World War II in Vancouver. When the elderly men showed her formal portraits taken in a studio, she saw that the seal on the cardboard frame bore the name Yucho Chow.

“After the sixth photo I googled him, and that’s when I discovered there was nothing on him, or a little bit on his photos but no photos of him and no information on who he was, and that started this journey,” Clement recalls.

Her curiosity led her on a decade-long search to discover more about Chow, one photograph and one family at a time.

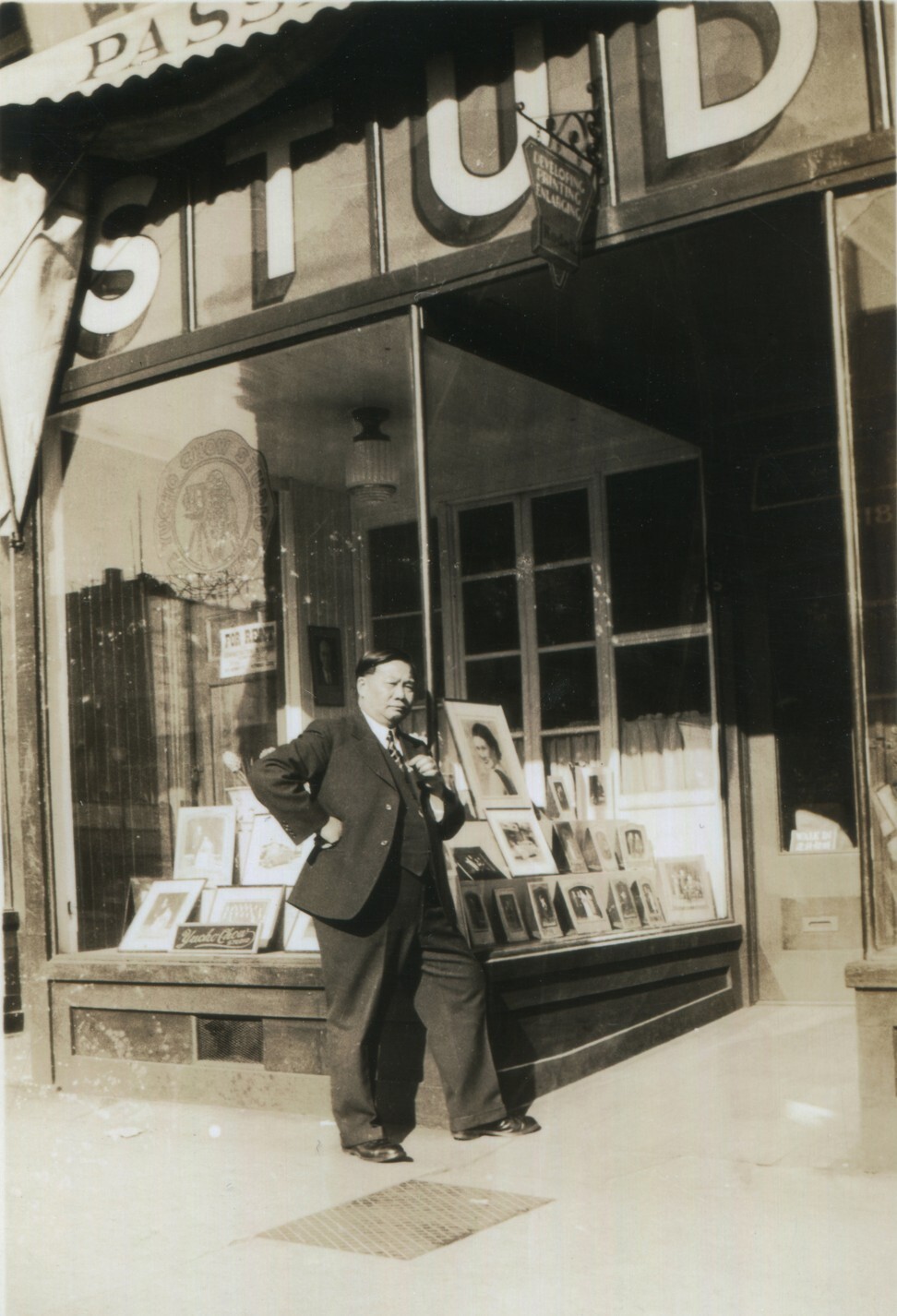

Many of the pictures Clement found were of young male Chinese immigrants in ill-fitting suits, or young families showing off their latest offspring to send to their families back in China. In her first five years working on the project, however, she still had not seen a photo of the man himself.

“He was like this phantom, this ghost. His work was everywhere but he was nowhere. I was trying to imagine what this man had looked like.”

Then, sometime around 2015, Clement interviewed the wife of a veteran in her late eighties and asked the woman about her story. When she said Chow was her grandfather, Clement immediately asked if she had pictures of him.

Biggest photo archive of 19th century China needs a new home

“He looked better than I thought,” she says. “He was robust, a little bit like a teddy bear, huge grin. He smiled in photos in a time when you didn’t smile. He loved his cigar, he was a bit of a showman. That became clear in some of his photos. Big fat round cheeks.”

A year later she worked on a project that involved displaying scenes from Vancouver’s Chinatown history on empty shop windows in the neighbourhood, and set one aside for Chow’s work. “For the first five years I only saw photos he took of the Chinese community, so I thought he was a Chinatown photographer; he’s Chinese, he’s taking pictures of Chinese,” she says.

Then she got a big surprise. National media coverage of the Chow window triggered a flood of messages from people of other ethnic backgrounds, including from the black, Sikh and Eastern European communities.

“I got my first email from somebody who said she was from the early black Canadian community, and said when she was growing up all her friends and families had Yucho Chow as their photographer,” Clement recalls.

“Another one called me from the Sikh community to tell me no one [else] would take their photo, that he documented all their major funerals, marriages, and came into their temples. He said, ‘He was one of us because he would take our photo’.”

Coverage of Clement’s exhibition led other Canadians to unearth old photographs from dusted-off photo albums in basements, attics and storage rooms. This triggered intergenerational dialogue across Canada, in which young people asked parents, relatives and grandparents about who was in these photos and the stories behind them.

“It was this huge tapestry of people and communities that have not been represented so far in our public archives,” Clement says. “It truly showcases Vancouver in its entirety, all these missing communities that were part of building this city and province.

“What I love is it’s these ordinary people whose contributions would be forgotten had we not had this photo and heard their story. Chow’s legacy in some ways is not just his photography, but all these stories that are attached with it that we now have in this massive archive.”

It took Clement eight years to collect some 200 photographs, about half from public archives and classified as the work of an unknown photographer that she later discovered were Chow’s. Within two more years she had amassed a collection of over 550 of his images, all original family portraits.

From the 1920s and 1930s, so many of these photographs were taken here with the intention of sending them back home to China, and it made me realise there are probably a lot of Yucho Chow in China and Hong Kong

An exhibition of 80 photographs Clement collected was shown at the Chinese Cultural Centre in Vancouver’s Chinatown in May 2019, and a 344-page book of his pictures was published the following year.

“It’s a story of one man who unintentionally documented all this history without even realising it,” she says. “It’s a story of tolerance and acceptance between groups who were lower down on the rung of society at the time, and of how similar we all were, even when we came from very different corners of the world, spoke different languages, dressed differently, had different skin colours. When you see all these photos together, people shared the same aspirations, dreams and needs.”

There is very little information to be found about Chow himself. What is known is that he was born in Hoy Ping – now Kaiping, in the southern Chinese province of Guangdong – in 1876 and left his young family to migrate to Vancouver in 1902, paying the Chinese head tax of C$100. He started out as an interpreter and letter writer for illiterate migrants.

His grandchildren are not sure how Chow learned photography, but he saved up enough money to buy a camera and set up his studio in 1906 in Vancouver’s Chinatown, relocating within the area a few times until his death in 1949.

Clement notes Chow’s enterprising attitude. The banner on his shop read: “Rain or Shine”, and “Anything, Anywhere, Anytime”, which theoretically meant he was available 24 hours a day, because he slept in a cot at the back of the studio to save on living expenses.

The curator points out cameras were expensive in Chow’s time and having a photo taken was a special event; people saved up money to have their pictures taken. Some of Chow’s photos show two Chinese men posing – perhaps from the same village, or friends or relatives – in a bid to save money during the Great Depression.

People dressed in their best, even borrowing clothes to give the impression of success.

Chow also took photos of performers who had Vancouver on their itinerary, including Chinese opera stars, vaudeville players, musicians, and acrobats looking to acquire new promotional images. Perhaps the most famous person Chow photographed was the Chinese republic’s provisional first president, Sun Yat-sen, who visited Vancouver in 1910 or 1911.

Clement says Chow’s studio remained open during both world wars, the Spanish flu epidemic, Asian race riots and the Great Depression. Children appear in the 1920s and 1930s – a new generation born in Canada.

While most photographs were meant to mark happy events, some were of remembrance. When Clement scanned images in a high resolution, she noted a few included people that had been superimposed, in a primitive version of Photoshop.

In one family picture, the wife had recently died and her head was superimposed onto the body of another person; or a picture of a Sikh woman taken many years earlier was placed next to her now older husband to make it look as though they were both physically present.

As Chow prospered, he was able to rise into the merchant class and bring his second wife and daughter, who were exempted from the head tax, to Vancouver. His eldest daughter, Mabel, became his assistant, carrying his heavy camera equipment – some of which were later donated to the Museum of Vancouver – while his third daughter, Jessie, soon became proficient at hand-colouring his photos.

One day in 1949, Chow fell ill in his studio and was rushed to hospital, where he died at the age of 72. Clement says his illness was related to his heart, with his weight and cigar smoking factors in the illness.

A year later, two of his sons – Chow had 10 children – Peter and Philip, took over the studio and worked there for almost 40 years until 1986, when they retired. Clearing out the studio they found thousands of negatives. Their children recall that five truckloads of negatives were taken to the local dump.

In addition to the 550 photographs Clement managed to collect, there are thousands more out there, she believes.

“From the 1920s and 1930s, so many of these photographs were taken here with the intention of sending them back home to China,” she says, “and it made me realise there are probably a lot of Yucho Chow in China and Hong Kong.”