‘The captain of the boat would not allow us to swim in the river,” says Sebastião Salgado. “There were a lot of caiman about. They are so big in Amazônia – they’re the size of crocodiles. There are lots of constrictor snakes, too. They are not poisonous but they are huge. When one catches you, you’re finished. It will break all your bones and eat you. Then there are the piranhas.”

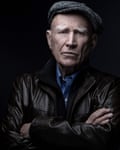

Salgado is not just talking to me via Zoom from Paris, where he has his studio. He is leading me on a breathless quest into Amazônia, the world’s most extensive rainforest. The photographer, clearly enjoying himself, admits that his favourite moments in life are when he’s setting out on a journey. “I am inside my transport – a plane or a boat – anything that brings me there. I am going to see something!”

We are talking about his hefty new photography book Amazônia, a stunning succession of black and white panoramas. Looking through his images, I feel the same awe I would feel in front of sublime paintings: serpentine rivers flow through seemingly limitless forests, sheer-sided rock escarpments vanish into skies, and apocalyptic clouds loom over wispy treetops. Yet Salgado does not talk about his work as art. He speaks of it as a journey, an adventure story, a history of the world.

Salgado has photographed some of the most extraordinary scenes Earth has to offer: gold miners crawling like termites up the muddy sides of a giant pit, refugees clinging to life in dusty wastelands, oil wells ablaze in the deserts of Kuwait. But exploring the Amazon region of his native Brazil, with its hard-to-navigate tributaries, was a new challenge. He almost lost an eye and now has an implant in his knee, after two accidents. And, while those dark waters in his pictures may look calm, they are not to be trusted. At one point, he hired a big riverboat capable of carrying 100 people, even though it was just for him, his team, their equipment and food supplies.

They were tempted to swim – until the captain issued that warning. So they fished instead. Salgado gets out his phone – yes, the master of the massive jaw-dropping monochrome is not above taking snaps with his mobile – to show me a picture of a fish the captain caught. Held upright, it is taller than the skipper. “You see,” he says, “things are so huge in Amazônia: a big fish three metres long! This is a fish that’s 250 kilos. The waters, when you navigate the black river, are 80 metres deep on average. Some places, the river is 20 kilometres wide.”

That riverboat journey was an attempt – doomed as it turned out – to find the source of one of Amazônia’s rivers, as well as a chance to take photographs of riverbanks that look like huge walls of trees. But to reach his ultimate destination, the communities who live deep in the forest, Salgado needed to navigate smaller streams in narrower boats. His book contains a shot of 10 or so small vessels moored at daybreak: dark and sharply focused, they stand out from the misty, featureless landscape behind, their seats catching the morning sun and shining silver. Whose are they?

“The majority are boats I hired. You are not allowed to hunt the food of the Indians or catch their fish. Anything I need to eat on that part [of the journey], I must bring. I must bring a pharmacy, my equipment, my studio. I have 12 men, guys who know how to operate the boats because it’s very specialised. The big river is not a problem, but you must take care in the small rivers or you will destroy the boat. And I must have what we call in Brazil a Captain of the Jungle: a guy who knows the jungle, knows how to hunt and fish, how to walk inside the jungle, how to set up camp. And I have my assistant from Paris, one or two translators, an anthropologist, and one agent from Funai.”

Funai is the National Indian Association of Brazil, which supervises all contact between outsiders and indigenous communities. “When you look at the map of Amazônia, all the Indian reservations are intact. They don’t allow destruction inside their land. The Indian land in Amazônia is about 25% of all Amazônia. Brazil had fabulous behaviour before President Bolsonaro. Brazil recognised the Indian territory. When you see the Indian communities in the United States, in Canada, the Aborigines in Australia – they lost their land. In Amazônia, no.”

Salgado, now 77, had to work closely with Funai to meet the peoples who appear in his photographs. In each case, they were first asked if they wanted him as a guest, then there were complex forms and permissions required, followed by a journey upriver into the heart of Amazônia, by helicopter in a few cases. Then came quarantine to protect the tribes from modern germs. All this was to reach communities who have contact with the outside world. Many don’t. “In Brazil alone, we have 102 tribal groups that have never been contacted – never.”

Leafing through his pictures, I am struck by a group of indigenous men looking across the forest to a mountain enveloped in moisture and mist. It is a holy mountain, they believe, where a god lives. “They are the Yanomami, the biggest ethnic group of South America. There are about 40,000 Yanomami. They are a mountain people who have four languages – some cannot understand the others. Their territory must be the size of England. There are a few groups of Yanomamis that have never had contact. They are completely isolated.”

The problems of Amazônia are well known and urgent: fires, deforestation, intrusive agriculture, roadbuilding. But Salgado – who with his wife, Lélia, has turned the family farm in Aimorés into a nature reserve that’s a model of reforestation – shows there is still much to fight for. The modern world, for all its rapacity, has only destroyed “a little bit of the periphery. The heart is there yet. To show this pristine place, I photograph Amazônia alive, not the dead Amazônia.”

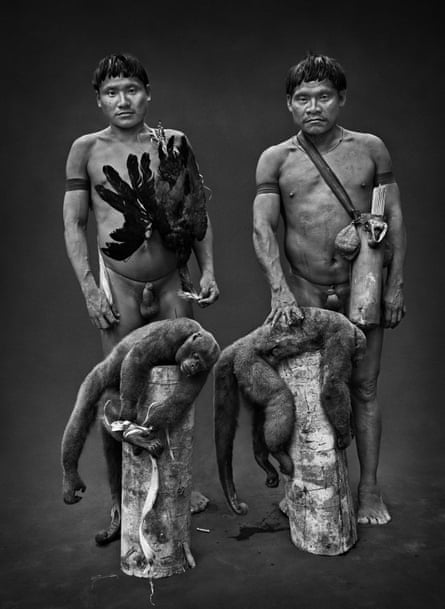

His landscape pictures capture the sheer scale of the still-unspoiled heart of this wilderness. His portraits, meanwhile, take us deep into the worlds of the people he sees as its lifeblood. They pose for him in feather headdresses with painted faces, or unadorned and naked. He’s not afraid to respond to them with frank emotion. I pause at a portrait of two women, one of whom looks at us with melancholy grace. “She’s beautiful,” he says.

The woman is also Yanomami, but from a community 1,000km from the men gazing at the mountain: in this huge space, peoples can vanish and resurface over the centuries. Salgado has an eye not just for people and place, though, but for time itself. His deep spaces, powerfully etched in monochrome, seem to recede into infinity, containing the ages. No wonder the photographer sees the Amazon as the river of human history.

“America was empty of humans 20,000 years ago. Homo sapiens evolved in east Africa and, 20,000 years ago, with the last glaciation, crossed the Bering strait and came inside America. Slowly, they went south.” In Amazônia, ways of life are preserved – and these connect us, Salgado believes, with early Homo sapiens. “When the Portuguese and the Spanish arrived in America, who did they meet? They met themselves. They met Homo sapiens that had arrived 19,000 years before them. When I walk inside this land, I am walking inside my human community.”

Although the tribes do some farming, they largely rely on hunting, fishing and gathering fruit, just like their hunter-gatherer forebears. Some of Salgado’s most startling shots show proud hunters carrying dead monkeys home to eat. Yet, he points out, they live in rhythm with nature. When a village gets too big for its ecosystem, it voluntarily splits and part of the community moves to fresh forest. Salgado admires, even envies, the balance their lifestyle allows. “There’s fish in the rivers, animals in the forest, fruit in the trees. They live so well. They have so much time to discuss, to sing, to have parties.”

In the communities he lived with, he saw little hierarchy or power structure. “Once I was working and a kid started to jump in front of me. I asked my translator, ‘Please talk to the boy – he’s destroying my pictures.’ And she came back very disturbed. She said, ‘Sebastião, it’s impossible, because they don’t know how to say no. If a kid of five wants to climb a tree 20 metres high, he can. The mother won’t tell him not to, because they don’t know oppression.” On another occasion, he told a made-up story about a jaguar as a joke, leaving one man so shocked he never spoke to Salgado again. “They don’t know lies,” he says.

The first Europeans to visit the New World brought back reports of its indigenous peoples. Some told horror stories of cannibals. Others spoke of a natural society where people were equal and contented. Salgado sees Eden itself in the depths of his own country’s great wild place. “Paradise exists,” he says. “Amazônia is paradise on earth.”

This article was amended on 21 June 2021 to correct the spelling of Bering strait.

Amazônia by Sebastião Salgado is published by Taschen. The exhibition is at Philharmonie de Paris until 30 October.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion