If you could press a button and eliminate social media platforms from the world, would you do it? Listen to the testimony of Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen over the last month and it might appear that turning back the clock is a no-brainer. Haugen revealed to legislators in the US and UK how Facebook pursued policies it knows to be harmful – algorithms that push out a diet of misinformation, rage and hate – in the cause of profit.

Many of us feel the toxic impacts of social media even as we enjoy its benefits: the natural inclination to harden your position after being subjected to a torrent of abuse from people on the other side. The attraction of reading and liking content that shores up, rather than challenges, your beliefs. The knowledge that much of your motivation in sharing those holiday snaps is showing off. But it’s unhelpful to talk about social media harms as though its users are a homogenous mass. Not everyone is equally susceptible and an emerging research base points to traits such as low self-esteem, insecurity and anxiety that might make some people more vulnerable to social media’s darkest corners: radicalisation into ideologies such as the far right, Islamist extremism or violent misogyny; the social contagion of self-harm; and the conspiracy theories that underpin contemporary anti-vax sentiment.

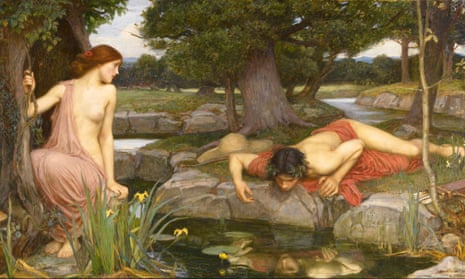

However, this only takes us so far in understanding social media harms. One of the most worrying aspects in terms of the polarisation of political debate is its interplay with a psychological trait not typically associated with vulnerability: narcissism. People with narcissistic traits tend to have an inflated sense of self-importance and entitlement, crave admiration, expect special treatment, don’t take criticism well and lack empathy. Narcissism manifests in two forms: grandiose narcissism, typified by the charming and charismatic extrovert, and vulnerable narcissism, characterised by anxiety, hypersensitivity to the perceptions of others, insecurity and shyness. In its most extreme form, it is a personality disorder.

A dash of grandiose narcissism in our public sphere is not a bad thing. Saintliness is a rare character trait: most good in the world is achieved as a result of mixed motivations, people who want to do good things because of how it makes them feel and what it does for their status, as well as what it does for others. But social media has elevated narcissism far beyond what is healthy.

Social media is the narcissist’s playground. Through likes and shares, it re-engineers their social feedback loop towards the superficiality they thrive on, fuelling a sense of superiority and rewarding manipulative tendencies. Perhaps it is little wonder that narcissists are more likely to become addicted to social media. Interestingly, studies suggest that narcissists on the right show greater tendencies towards entitlement and those on the left towards exhibitionism, craving validation. Narcissists are also, perhaps unsurprisingly, more likely to engage in online bullying; for those purporting to be in it for moral causes the ends justify the means. And there is evidence that a platform such as Facebook itself increases narcissistic tendencies in people.

This online elevation of narcissism has profound real-world consequences. People with narcissistic traits have always been more likely to be politically engaged; social media has amplified these effects, affecting who dominates the public discourse within political parties and media debates. The ability to command vast numbers of likes is often seen as a reliable indicator of someone’s level of insight and potential contribution.

On the left, it plays into an emerging divide about how to bring about progressive social change. One way is to build solidarity between different groups in a way that emphasises common belonging and making people feel good about themselves for joining socially just causes. Another is to make imperfect people feel guilt and shame for their moral ineptitude, for their failure to see the world through the right lens. Social media narcissists pull left-leaning movements towards the latter model of hating on people perceived to think the wrong way, which is destructive to social change but much more thrilling than the boring, old-fashioned work of building alliances across divides. Victory is people being shamed and bullied for minor or nonexistent transgressions, rather than winning hearts and minds. No matter if the punishment far exceeds the crime: a narcissist’s moral certainty dehumanises those who fall foul of their creed.

Not only that, there is a risk that performative virtue-signalling becomes a displacement activity for working to achieve real change. Liking a post or signing an online petition delivers the feelgood hit of being on the right side of history, without any of the real-world impact. And the more that activists model this form of brand-driven campaigning, the more it lets the rest of civil society off the hook. It helps multinational corporations to get away with signalling their commitment to LGBT inclusion in Pride month or to antiracism in Black History Month on social media in countries where this is brand- and sales-enhancing, while doing no such thing in countries where human rights abuses are rife.

A core tenet of political liberalism is that the only way for societies to arrive at the right answer is to air all sides of the debate. A long underemphasised aspect of this is that changing people’s minds is almost always more about how an argument is framed than its content.

Take the successful referendum campaign for abortion reform in Ireland: the case for liberalising abortion was presented to those who were sceptical in pragmatic, rather than rights-based terms; the terrible cost of an abortion ban for people’s mothers, sisters and daughters, rather than an abstract woman’s right to choose.

The most successful campaigns for social change win people round by making the case in terms that resonate with them, not with a campaign’s most ardent backers. But in a world where the economics of social media platforms are increasingly driving a more narcissistic form of campaigning that is characterised by a lack of empathy and generosity, that becomes ever harder.