Beijing’s efforts to rein in the power of tech companies stepped up last week, when four top internet regulators issued new rules on the use of algorithms — the technology that drives popular products like ByteDance’s news aggregator Toutiao and microblogging site Weibo. China’s regulations — the first of their kind anywhere — are a direct attempt to blunt algorithms’ influence over user behavior, a trend troubling governments the world over.

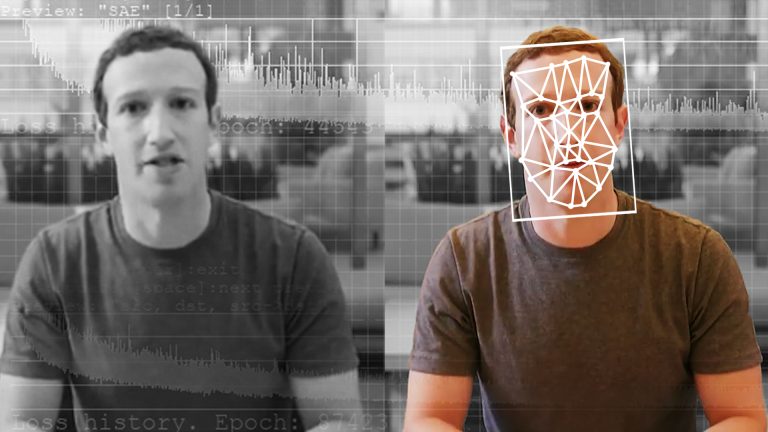

One part stands out as ambitious, and untested. Under the new rules, social platforms like Douyin, China’s version of TikTok, are forbidden from including “synthetic” content in their recommendations. The phrase used in Chinese, “合成虚假新闻信息,” is a catch-all term that refers to false information, fake news — and deepfakes, all of which are notoriously difficult for those same platforms to detect and eliminate.

In the U.S. and other jurisdictions, there is little recourse for harms perpetrated by deepfakes, and existing laws largely put responsibility onto the creators for uploading fake content, which protects companies like Facebook and Twitter. China’s new rules turn that responsibility on the platforms. Effective from March 1, the rules apply to internet platforms that use recommendation algorithms in China. Here’s what to know about the move.

What is the policy?

It’s designed to ban apps like Toutiao from pushing manipulated media to their users via “Read next” or “Watch next” recommendations on timelines, and news feeds. An earlier prohibition already banned online news providers from using tools like machine learning and VR to create or share false information and required them to label it if detected. The new rules specify that platforms that use large amounts of data to personalize content can’t use their powerful algorithms to generate fake news.

China’s new regulation ramps up pressure on the companies that make those apps. In countries like the U.S., platforms are protected by existing laws, like Section 230, which shield platforms from liability for the content that users post, meaning most of the methods for accountability focus criminal charges on the creators, Mathilde Pavis, an academic at the University of Exeter who has advised several governments on deepfake legislation, told Rest of World.

By focusing on platforms, she said, China is taking “a different approach, a very pragmatic approach — because the deepfake makers are really hard to track in practice.”

What’s motivating the regulation?

The regulations target the spread of false information that could lead to scams or social instability. But possible avenues for creativity, satire, and expressions of dissent could also be caught in the dragnet.

The new policy makes it the platforms’ responsibility to ensure nothing false or unapproved is generated by their powerful recommendation algorithms. This applies directly to online news sources like Toutiao. But many popular Chinese entertainment platforms, like Kuaishou and Bilibili, also use algorithms to deliver targeted content to users.

Restrictions on news outlets in China are notoriously tight, and online news aggregators like Toutiao are already allowed to share information from only an approved list of sources. But like many Chinese regulations, the terminology leaves room for interpretation. “The wiggle room is whether ‘新闻信息 [news information]’ covers all types of news,” said Qiheng Chen, an analyst at Compass Lexecon who has contributed to Stanford University’s DigiChina Project. “I can imagine algorithms generating news on sports games faster and more accurately than humans.”

And while deepfakes can be harmful — spreading nonconsensual pornography or misinformation — manipulated media can also be a powerful tool for expressing humor, dissent, and social critique, said Sam Gregory, program director at the U.S. nonprofit Witness. In a recent report for the organization, the authors highlighted how humorists like Brazil’s Bruno Sartori used deepfaked videos to parody president Jair Bolsonaro, soundtracking his constant scapegoating of the country’s former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva with Mariah Carey’s “Obsessed.” It’s this kind of expression that Gregory worries will also be targeted with China’s new law.

“In a global human rights framework, you should never regulate satire just because it pokes fun at the powerful,” said Gregory. “But that isn’t necessarily a shared norm.”

What are the issues with following through?

Deepfakes and manipulated media are notoriously hard to detect. Artificial intelligence needs a massive dataset of examples to learn from. This means that only the largest platforms would have the tools and datasets necessary to detect synthetic media, said Gregory. Even the most sophisticated algorithms for detection are still not highly accurate.

Automated deepfake detection has become possible in only the past three to four years, Gregory told Rest of World. “Deepfake detection tends to only work well if you know the method of how the deepfake was created, and when you’re working with high-quality media.”

Though China may be the first country to institute this kind of policy, it’s far from the only country trying to regulate manipulated media.

The new rules also leave open the possibility that the government could audit the platforms’ algorithms to ensure they’re targeting and removing synthetic content. Some violations, such as whether an algorithm uses discriminatory key words to target users, are difficult to determine without reviewing the algorithm’s code.

The law also requires recommendation algorithms that hold influence over “public opinion” to be submitted for a security review, but it’s unclear what details are required. “It’s going to raise serious questions for companies doing business here, in terms of how much the government has access to their code,” said Kendra Schaefer, head of tech policy at Beijing-based consultancy Trivium China.

What are the consequences if they fail to be effective?

The new algorithm regulations explicitly target platforms that hold influence over public opinion. They’re focused on curbing anything that could cause social tensions to flare — not just the spread of unapproved information but also actual falsehoods and persistent internet scams, including those that target elderly people. The regulators are “covering their bases in all the different ways algorithms could be used to erode national unity or exacerbate existing social problems,” said Schaefer.

If platforms are found to be in violation of the rules, they can face penalties of up to 100,000 RMB (about $15,600) as well as criminal prosecution. They’re also required to comply with requests to correct information, cease updates or adding new content, and submit to security reviews, depending on the infraction.

These restrictions build on the earlier prohibitions from 2019, said Jeremy Daum, founder of collaborative translation site China Law Translate and senior fellow at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center. “Combating fake news is an ongoing struggle everywhere, and China has been on it for a while,” he said. “That includes the fear of people spreading antigovernmental sentiment or criticism of policies.”

Do governments battling similar issues with fake content have anything to learn?

The rules are “groundbreaking,” said Helen Toner, director of strategy at the Center for Security and Emerging Technology at Georgetown University. By focusing on recommender systems, they’ll be among the first regulations to yield “initial data about what it looks like to enforce restrictions on these kinds of artificial intelligence systems” and “influence future similar efforts in other jurisdictions,” Toner told Rest of World.

Though China may be the first country to institute this kind of policy, it’s far from the only country trying to regulate manipulated media. Legislators in the U.S., U.K., and the European Union have all begun crafting regulations and proposals to curb the power of algorithms and address deepfakes, though existing protections for platforms and free speech would likely prevent any laws as sweeping as China’s. But following a year of crackdowns on tech companies for everything from anticompetitive behavior to price discrimination, Beijing has demonstrated a willingness to use regulations to wipe billions in market capitalization from the country’s largest tech companies, in order to keep them in line with government goals.

Like any new policy, there’s going to be ups and downs, said Schaefer. “The rest of the world, frankly, are going to learn a lot as China feels its way forward on this one.”